The Modern View of Still Life Painting

Impressionism is perhaps the most important movement in the whole of modern painting. At some point in the 1860s, a group of young artists decided to paint, very simply, what they saw, thought, and felt. They weren’t interested in painting history, mythology, or the lives of great men, and they didn’t seek perfection in visual appearances. Instead, as their name suggests, the Impressionists tried to get down on canvas an “impression” of how a landscape, thing, or person appeared to them at a certain moment in time. This often meant using much lighter and looser brushwork than painters had up until that point, and painting out of doors, en plein air. The Impressionists also rejected official exhibitions and painting competitions set up by the French government, instead organizing their own group exhibitions, which the public were initially very hostile to. All of these moves predicted the emergence of modern art, and the whole associated philosophy of the avant-garde.1

Julie has been showcasing many of the Impressionists in her posts but what did these artists think of Still Life? Did they paint in this genre at all? We do tend to associate this period very much with landscapes, especially created en plein air.

My research has shown that some of the Impressionists certainly did paint still lifes with Claude Monet (1840-1926) leading the way. In fact, Monet painted sunflowers before Vincent Van Gogh did.

Camille Pissarro (1830–1903) painted a few still lifes and as you can see from the wallpaper he set up the objects in the same room and most likely painted them at the same time.

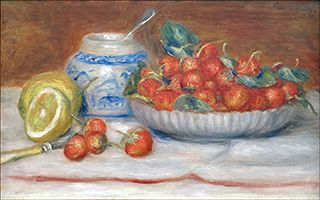

On the other hand Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919) created quite a number of paintings in this style with hsi characteristic beautiful control of quick brush strokes and a palette to delight any eye. Compare his works with those of Pissarro's above and note how the delicate light brings alive the subject matter.

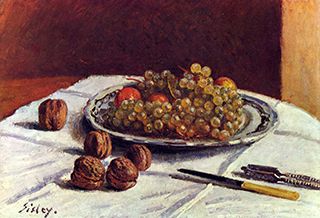

And in marked contrast, the still life paintings of Alfred Sisley (1839–1899) are more dramatic and executed with a much heavier brush stroke and careful placement of each object even to the arrangement of the dead heron.

It was however the Post-Impressionist who took on perfecting a still life painting as never seen before. We all know Vincent's vases of sunflowers and never tire of appreciating them but today I want to show you a couple of Van Gogh Still Life paintings that are of everyday household objects - both paintings done when he was living with his parents in Nuenen in 1885.

The background in the still life on the left is almost the same colour as the three bottles. Van Gogh used white paint to add light accents to the bottles – highlights. This makes them stand out from the background. For the painting on the left below Vincent used a canvas on which he had previously painted a woman at work. An X-ray image brought that fact to light.3

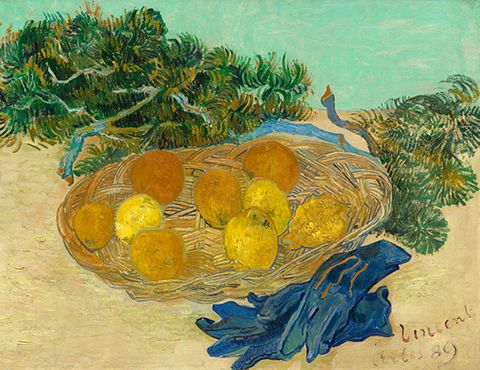

One of my favourite Van Gogh Still Life paintings is Still Life of Oranges and Lemons with Blue Gloves, 1889 as shown below.

Vincent was clearly attracted to the shapes and hues of the citrus fruit arrayed in the wicker basket, and the way their varied orb shapes play against the weave of the dried sticks, the whole set off by the prickly needles of the cypress branches. Van Gogh refers in his letter to an “air of chic” in this picture, prompted perhaps by the inclusion of blue garden gloves. The painting reveals the artist’s extraordinarily original sense of color, as well as his richly expressive paint application as he struggles to evoke the nubby waxen skin of the various fruits, the spiky fur of the branches, and the limp material of the worn gloves.4

But the modern master of Still Life wasn't Van Gogh or Renoir but someone who followed in the steps of his tutor Camille Pissarro. You can all start guessing as to who this was in the Comments box below and I will leave it a day or so to reveal the name.

Credits

1. theartstory.org

2. eclecticlight.co

3. vangoghmuseum.nl

4. nga.gov