Theatrical Realism

Lately, with Jane of Sandringham, I have been taking you on a journey through aspects of puppetry and opera. To provide a background to Theatre as an Art Form we are going to look at some of the elements that are used to present a performance, specifically Theatrical Scenery and Costumes.

Some years back I was asked to help paint the setting screens for a local school play. I was given a large rectangular canvas and had to paint a dormitory scene. I assumed that the scene was to be horizontal and painted it so.

There were shrieks when the scene was collected from my studio as the play producers had expected a vertical scene to fit the stands from which the scenery was to hang.

Some quick cutting up and resewing was done and all was well. But I learnt how thwart with problems the theatre world can be and how hysterical theatre people can be when the opening night is looming!!

As far as the western world is concerned we can thank the Greeks for introducing the concept of theatre as early as the C6th BC.

But I’m going to fast forward to the C19th and introduce you to the concept of Theatrical Realism. Theatrical realism was a general movement in 19th-century theatre that developed a set of dramatic and theatrical conventions with the aim of bringing a greater fidelity of real life to texts and performances, heralding the coming of modern theatrical works.

Below is a scene from a 1922 silent movie A Doll's House starring Alla Nazimova and Alan Hale, Sr. The author of the original play Henrik Ibsen was an influential exponent of realism in the theatre. (en.wikipedia.org)

In a conversation with Harald Holst (a member of the Christiana Theatre) Ibsen said that every scene and every picture ought as far as possible to be a reflection of reality. There must be equal truth to life on all counts. (bartleby.com)

Prior to this time theatre scenery was minimal and the costumes and text carried the drama. Here is an engraved print of the interior of the 17th-Century Duke’s Theatre - a very ornate theatre but no scenery - and certainly no realism.

What I do want to do today is introduce you to Lucia Elizabeth Vestris (née Elizabetta Lucia Bartolozzi, 1797-1856) an English actress and contralto opera singer. Here is Lucia as Pandora at the Olympic Theatre in 1831.

The first Olympic Theatre (below) was built in 1806 on the site of Drury House (later Craven House) and later renamed as Little Drury Lane. In 1830 Lucia Elizabeth Vestris leased the "house" and thus became the first female actor-manager in the history of London theatre.

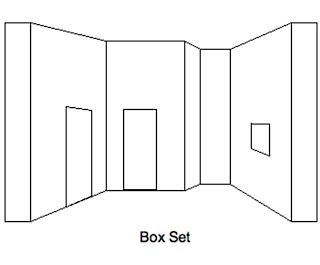

Madame Vestris (as she was known) with her business partner, Maria Foote, and later with her second husband, the actor Charles James Mathews, initiated several theatrical innovations, such as the use of historically correct costumes and more elaborate scenery, including a box set with ceiling, which she is said to have introduced in Britain. This is a diagram of the box set.

The Box Set creates the illusion of an interior room on the stage in contrast with earlier forms of sets in which two dimensional sliding flats with gaps between them created an illusion of perspective.

In the Box Set authentic details include doors with three-dimensional mouldings, windows backed with outdoor scenery, stairways, and, at times, painted highlights and shadows.The fourth wall was invisible (absent), separating the characters from the audience, and the ceiling was tilted down at the far end of the stage and up toward the audience. Doors slammed instead of swinging when being shut, as in reality.

The Box Set first appeared in 1832 in Madame Vestris’ London production of The Conquering Game by William Bayle Bernard. It gained wide usage by the end of the 19th century and is a common feature of modern theatre. (en.wikipedia.org)

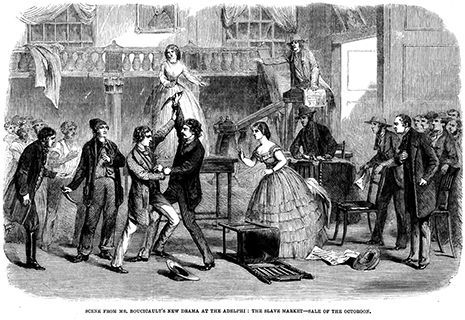

To illustrate the significance of the arrival of theatrical realism I have found this article and image (below) of a Scene from Mr Boucicault's New Drama: The Slave Market - Sale of the Octoroon, published in The Illustrated London News, 30 Nov 1861.

We have selected the "sensation scene" from Mr. Boucicault's new drama of "The Octoroon" for an illustration this week. This particular scene recommends itself from its truthfulness. In delineating the dreadful business which it represents, the dramatist has attempted no exaggeration. He has treated it as a familiar horror, one which society has accepted as portion of the regular business of the market and legalised as an institution. However abominable it may be, it is authorised. Those who observe, and those who are actively engaged in the transaction, alike acquiesce in the fact and the principle, as if there were no outrage being done to nature, no sin against humanity committed. Any external demonstration of excitement would be improper. What conflict there is goes on within. That beautiful Octoroon--what feels she? They who would save her from the threatened degradation--what feel they? And in that determined wretch, who exceeds his means in her purchase--O! What a hell there is in his bosom, of premeditated guilt, and even already of an anticipated remorse! The picture is presented on the stage in fine taste.

Nowadays, especially in terms of film, we have gone beyond realism. Having just seen Incredible 2 with a child I can assure you I don’t like the way the art of creating backgrounds to stories is developing. There is much to be said for the simple Box Set. We will continue to look a little more at theatre in the coming days.

A word from subscriber S of Wheelers Hill who has provided us with a newspaper cutting on Japanese Australian Artist Kyoko Imazu with her clay Yokai, which are “not too scary” for children.

Credit:

- en.wikipedia.org

- pinterest.com

- npg.org.uk

- britannica.com

- media.britishmuseum.org

- unmass.edu