The mystical appeal of Japanese fans!

What do you think of when I mention an item small enough to fit into your pocket or handbag, that can be be used to send messages and communicate with others, play games with, which became a popular must-have fashion accessory, and is something you may always want to keep handy?

No!! It is NOT your mobile phone!! It is a folding fan! Such was the popularity of Japanese fans by the late eighteenth century that this is exactly the status they held!

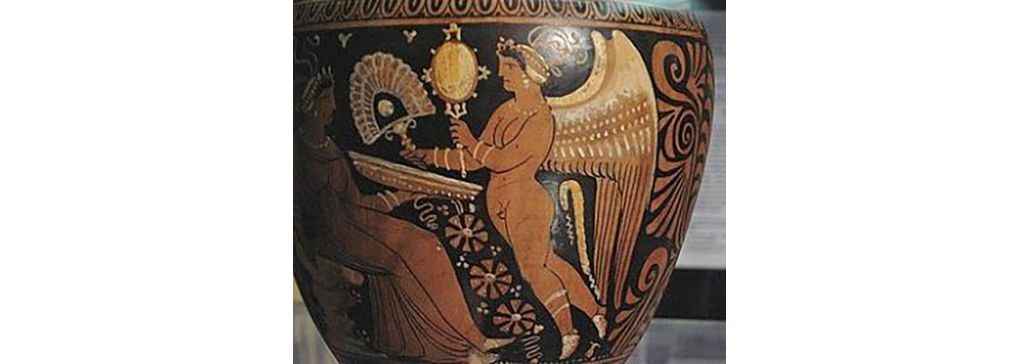

We know from wall paintings and stone carvings that the Ancient Egyptians used large ceremonial fans which slaves waved over their pharaohs and queens in the stifling heat.1

But the oldest known surviving fans, two woven bamboo hand screens, were found in a Chinese tomb dating to around 2 BC.1

The first fans in Japan are believed to have been introduced from China in the Nara Period (710-794). Hand-fans were imported into the Japanese court or were sent as gifts from the Chinese and Korean courts. These were the “fixed” fan, called Uchiwa, a circular shape, a bit like a ping pong bat, made of washi paper fixed to a bamboo stick.1

They were mostly used by the aristocrats and samurai (upper) class to shield a lady's face against the glare of the sun or the fire, or hide from recognition by a commoner.1

The folding fan, the Sensu, was thought to have been created by accident in the Japanese Court in the 6-9th century AD. Japan then introduced this new style back to China.2

Fans were not pieces of artwork initially. In fact, it was many centuries before fans were considered an art form worth pursuing properly. Initialy, they were used for communicating messages and recording maps, textbooks, prayers, calendars, letters, court announcements and so on. The individual sticks were written on vertically, then folded together and tied at one end. They were also a way to signify social standing, whereby the number of inner pieces, or "sticks" that made up a sensu, was an indicator of social status.2

Women in court had specific folding fans that they had to carry depending on their social standing and marriage; a symbol of their rank.2

Fans were also used in the military as a way of sending signals on the field of battle. War commanders would direct the soldiers through their movements. This Gunbai war fan, below right, also contains a concealed spear for your multitasking warrior!4

From the 15th-century fans were being produced all over Japan by dedicated, professional fan painters and makers, sought after for their quality and delicacy. Women's fans were more colourful and often bore painted flowers and had a decorative ribbon attached. Men's fans were plainer and larger.2

They grew to be so widely revered that Japan began exporting them abroad, including to China, from where they made their way onto the Silk Road trade route, to Europe.2

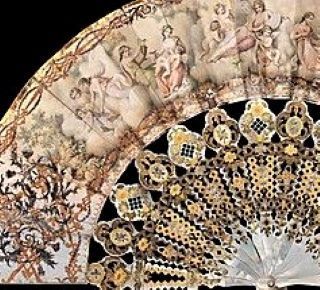

By the 17th century, fans had become a desirable fashion accessory for well-to-do European women of all social standings. Folded fans of feathers, silk, or parchment, were decorated and painted by specialised craftsmen and artists. They had reached a high degree of artistry and were being made throughout Europe.2

Even Queen Elizabeth I of England can be spotted in paintings holding a folding fan.

A well-known portrait of her, (below top left), painted in 1585–1586, attributed to John Bettes, and now housed in the National Portrait Gallery, London, shows her with a large ostrich feather fan set in a superb jewelled handle. The fan is given the same prominence in the portrait as the jewellery and costume, indicating that it was valued.3

The Edo period was a great time for artistic expression on the folding fan. Artists like Takushima Hokusai (of The Great Wave fame), and Takaku Aigai (1796–1843) created some beautiful traditional work.

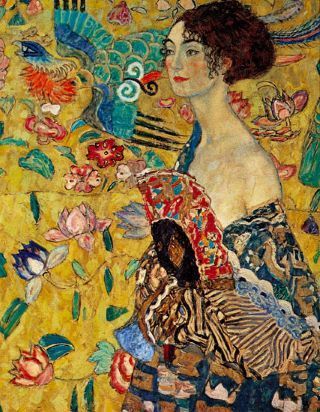

We know that some of the Impressionists, and even the symbolist Gustav Klimt in Austria, were greatly influenced by many forms of Japanese art.

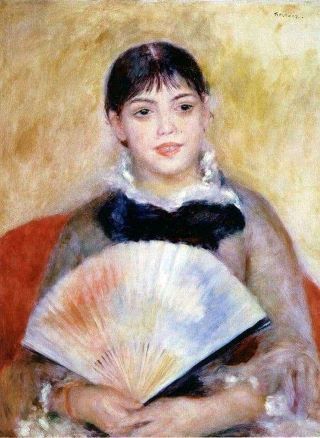

By the 19th century, sensu (folding fans) were appearing in the paintings of artists such as Gustav Klimt, Mary Cassatt, Berthe Morisot and Pierre Renoir, (all of whom we have featured in previous blogs). And of course there is the iconic painting "La Japonaise", which Anne featured recently in a Reflection blog.

By the Victorian age in Britain, women had even created a fan "language" where different gestures indicated different responses, such as touching the right cheek to mean “yes” and the left cheek for “no.” Closing your fan meant "I wish to speak to you."...... A fan snapped closed may have signalled jealousy, and a fan dropped to the floor was a pledge of friendship or fidelity……and so on!2

As mentioned, fans had a long military history as a signalling device used in war, and in time, the fan also became a part of kenbu which are Sword Dances which tell the story of important battles.1

After World War II, the Occupation Forces forbade the use of weapons in martial arts practice and entertainment, so kenbu (Sword Dance) performers fully substituted fans for their swords.1

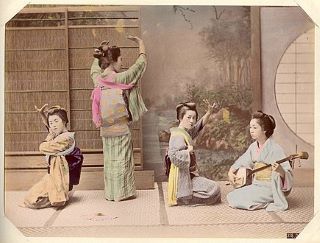

Fans are also used in most forms of Japanese performing arts: The Geisha, Japanese dance, Kabuki and Noh theatre, and rakugo, which is traditional Japanese story telling. The rakugo narrator kneels on a cushion and acts out the various characters with nothing more than a cloth and a folding fan!

Lastly, the most decorative of all the fans are brisé fans, which are carved from ivory sticks or solid wood, and some are very ornate:

If you would like to know more about the history of fans, there is more information at the website of The Fan Museum, Greenwich, London. Click here.

Lastly, we leave you with a traditional Japanese fan dance, set to the gentle accompaniament of the harp..........

Footnotes:

With thanks to:

- japanpowered.com

- supersimple.com

- encyclopedia.com

- japanobjects.com