Robin Boyd CBE: the Boyd Dynasty expands to include Architecture

So far on our journey through the generations of Boyd Artists we have met painters (in both water colour and oils), print makers, potters and illustrators.

Today we take off into a new area - architecture. Robin Boyd, son of Penleigh and Edith Boyd took the Boyd family artistic talent in a new direction and a very successful one.

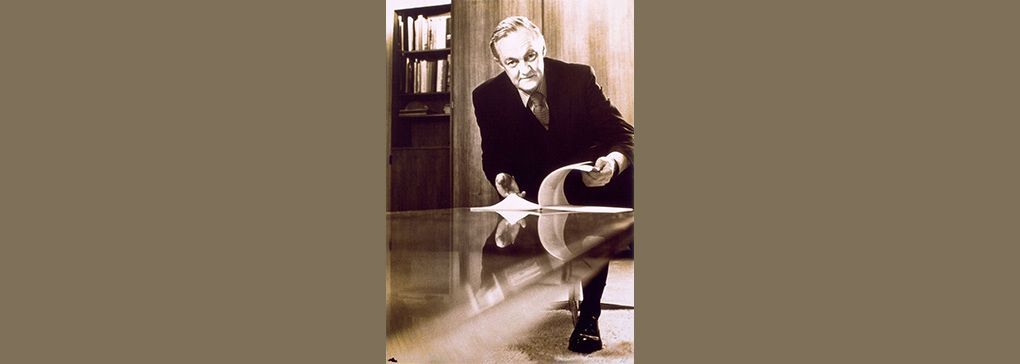

Robin Boyd CBE (1919-1971) is arguably the most influential architect there has been in Australia.

But unlike today, where architects tend to be noticed through creating the tallest building in the world, Robin Boyd's fame and reputation was literally built on the suburban home in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

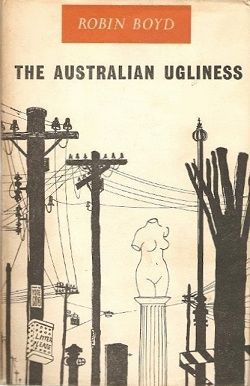

He certainly didn't like the look of the houses that surrounded him as he grew up in Melbourne. In essence, he saw the homes that started to appear after WWII as boxes that ignored the environment around them and failed to give Australia an architectural identity. Robin Boyd wanted to shock Australians out of their narrowmindedness and worked tirelessly, not only as an architect, but an educator and writer, to make us address what he termed in his famous publication The Australian Ugliness.2

Boyd's three main criticisms of the Australian urban landscape stemmed from three ideas:

1. the Australian obsession with "featurism"– a fixation on parts rather than the whole;

2. the use of building materials and styles that are unsympathetic to the country's landscape/climate;

3. and the culling of trees in order to "divert" drains, prevent leaf clogging and other immaterial issues. 3

Boyd's belief was that trees are not a feature, or a byproduct of design, but rather a fundamental landscaping necessity, something unrecognised by Australian homeowners and city planners who opt for low maintenance. 3

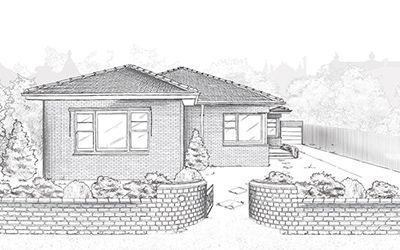

Below is a sketch of the typical brick veneer home being constructed in Melbourne post 1945 and right up until the mid 1960s.

An acute shortage of building skills, materials and equipment followed World War Two and led to a chronic housing shortage. Brick veneer - cheaper and faster to construct than solid brick - became archetypal of the era.

A revival of domestic building followed the post-war baby boom and widespread immigration. 4

Robin Boyd faced the problem of changing the mind set of Australians who had embraced what became universally known as the ticky tacky boxes. Of course this phenomenon wasn't peculiar to Australia and most of us who grew up in this era know the song Little Boxes, written and composed by Malvina Reynolds in 1962, and which became an international hit for her friend Pete Seeger in 1963, when he released his cover version.

The song is a political satire about the development of suburbia, and associated conformist middle-class attitudes. It mocks suburban tract housing as "little boxes" of different colors "all made out of ticky-tacky", and which "all look just the same". "Ticky-tacky" is a reference to the shoddy material supposedly used in the construction of the houses.3

Here is the wonderful Pete Seeger singing Little Boxes.

In 1947 the Royal Victorian Institute of Architects and The Age newspaper introduced the Small Homes Service, providing low-cost, off-the-plan, architecturally designed, small homes. Robin Boyd was its first director. 4

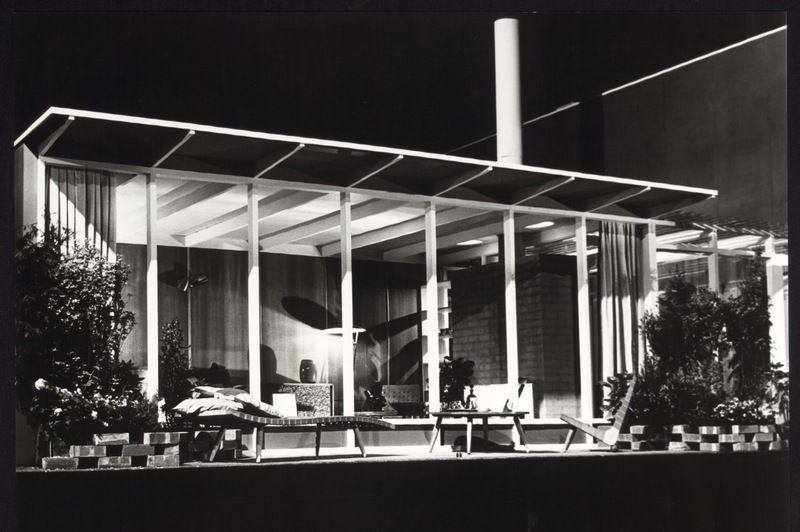

In 1949 Boyd launched his model of the House of Tomorrow, displayed by the Small Homes Service at the 1949 Modern Home Show at the Exhibition Building in Carlton Gardens, Melbourne. This was the first of a post-WWII explosion of modernist display homes. 4

Gradually Robin Boyd began to put his ideas into practice. One of the earliest examples of his suburban home design is called the Roche House built in Deakin, Canberra, ACT in 1954 for local doctor Hilary Roche. Note its long unbroken roof line, wide eaves, extensive windows.3

However, Walsh Street, the house Boyd designed for his own family in 1957, is his most well-known work. It has been extensively published both nationally and internationally as an exemplar of modernist Australian architecture and a house that continues to influence architectural thinking. It is now the home of the Robin Boyd Foundation.7

Take a moment to wander through this building which broke the mould of the conventional suburban box. It has a separate wing for the parents and a roof that moves in the wind! Plus many, many other interesting features.

Now that you have seen inside the private home of Robin Boyd I am sure you will be affected in some way by being Cast into the Enveloping Darkness.8

I will let Professor Philip Goad (Redmond Barry Distinguished Professor and Chair of Architecture) at the Melbourne School of Design, University of Melbourne describe the interior of the Boyd Walsh Street home for you.

The interior of Australian architect Robin Boyd’s second house for himself and his family in South Yarra, Melbourne (1957-9) is largely cast in shadow. Further, to use Japanese writer Junichiro Tanizaki’s phrase, the house’s ‘enveloping darkness’ is accentuated by the light absorbing natural textures of dark brown jarrah timber lining boards, recycled red bricks, off-sawn timbers, cork tiles and a sweep of untreated pine lining boards on the ceiling. And yet, almost as if invoking Tanizaki again, the Boyd house is enlivened by slivers of reflected golden light: the brass straps and brass canopy of the chimney flue, brass plates attached to each stair tread, gold chromed cupboard door handles, and a series of copper-backed saucepans glimpsed across the living room. There appears to be a fascination with the lustre of metal. However, this careful, almost decorative, orchestration of light and materiality occurs before Boyd had written his famous diatribe against ornament in The Australian Ugliness (1960) and before he had made his first trip to Japan to write the world’s first monograph on architect Kenzo Tange (1962).8

Clearly Robin Boyd was influenced by the architecture of Japan and also the Scandinavian countries. If you are interested in the Japanese influence on Robin Boyd's work you might like to read this article.

Robin Boyd's principles are still relevant today as discussed in the article below by Rory Hyde who argues that:

A new Small Homes Service would not be designing new homes to address this challenge. It would be geared toward adapting the existing housing stock to suit the needs of today and creating new opportunities to share space and resources – a Small Homes Adaptability Service.9

If you are interested in how to do better with less in terms of small homes architecture, please follow this link.

Robin Boyd CBE (1919–1971) was awarded the Royal Australian Institute of Architects’ Gold Medal in 1969, received posthumously the Architecture Critics Medal from the American Institute of Architects in 1973, and received an Order of the British Empire in recognition of his service to architecture in 1971, the year of his tragically early death. 10

The Artistic Tapestry of Boyd Family Connections

For those of you interested in this ramble through The Boyd Dynasty, I have just discovered further artistic connections. A cousin of Robin Boyd was Joan (Weigall) Lindsay (author of Picnic at Hanging Rock). She had married Daryl Lindsay, director of the National Gallery of Victoria, 1942 to 1956, and brother to artist Lionel Lindsay and renowned artist and author Norman Lindsay.(en.wikipedia.org)

Credits

1. portrait.gov.au

2. The Australian Ugliness by Robin Boyd, F.W.Cheshire, Melbourne,

1960

3. en.wikipedia.org

4. cv.vic.gov.au

5. collection.maas.museum

6. abc.net.au

7. robinboyd.org.au

8. 'Cast into the enveloping darkness': Robin Boyd and lustre before Japan by Philip Goad. In Proceedings of the Society of Architectural Historians,

Australia and New Zealand:33, Gold, edited by AnnMarie Brennan and Philip Goad,208-214. Melbourne: SAHANZ, 2016

9. architectureau.com

10. australiapostcollectables.com.au