Edgar Degas - A mercurial master of movement

Today we continue the series exploring the interactions and linkages of some of the French Impressionists, with a look at Edgar Degas.

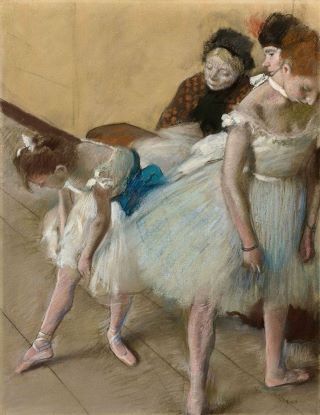

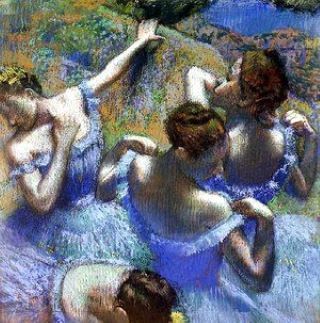

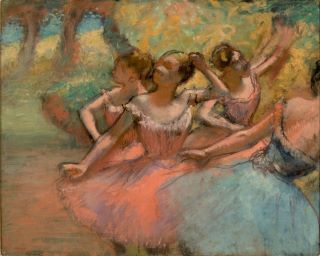

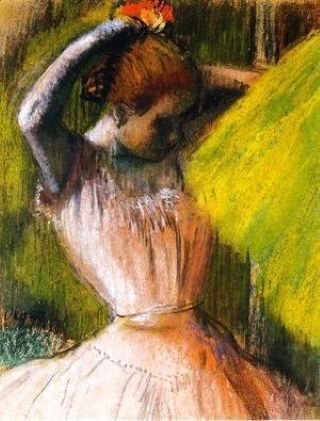

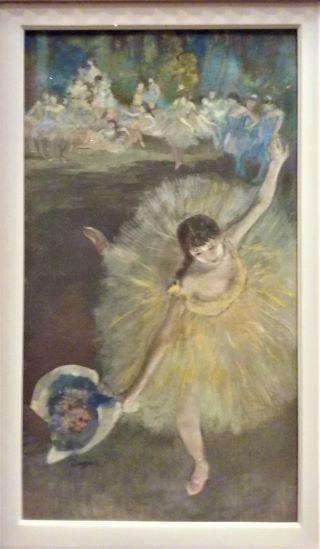

What is the first thing you think of in relation to Degas? Possibly it is ballet dancers? Whilst he completed over 1,500 paintings, pastels and sketches of ballet scenes, he is also known for other subjects of life, as well as photography and sculpture. (All images are courtesy of edgar-degas.org, unless otherwise stated).

Degas was a very big personality, strong minded and outspoken. While he associated with the Impressionists, and certainly exhibited with them many times, he thought and operated very differently to the group as a whole.

He was the chief organiser of many of their exhibitions, but somehow seemed to remain aloof and on the fringe. However, this appears to have been a deliberate principle in living his life, because he once said “The artist must live apart, and his private life remain unknown”.

Hilaire-Germain-Edgar De Gas was born on 19th July 1834 in Paris to a fairly well-off banking family, one of five children. Whilst he was a few years older than some of his fellow Impressionists, he followed a similar course in the development of his art styles. At age 18, he enrolled as a copyist at the Louvre, shortened his last name to “Degas” and chose to be known as Edgar.

In 1855 he entered L’Ecole des Beaux Arts , studying under Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. Here he met Edouard Manet, and they became good friends. He then spent three years in Italy copying the works of the Old Masters before returning to Paris. He exhibited in Le Salon for the next five years or so, following their prescriptive classical style.

The Franco-Prussian war of 1870 – 71 disrupted all life in France, and Degas went off to serve in the National Guard. During the war he was found to have a retinal eye disease which affected his eyesight and got worse as he got older, eventually severely impacting his ability to work.

When his father died in 1874, Degas discovered that his brother René had enormous business debts. To preserve his family's reputation, Degas sold his house and the art collection he had inherited, to pay off his brother's debts. For the first time in his life, he had to sell his artwork to make an income. Driven by this need, he produced much of his greatest work in the ten years beginning in 1874.

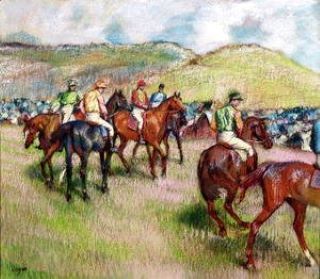

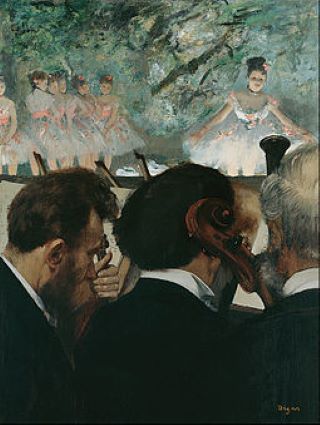

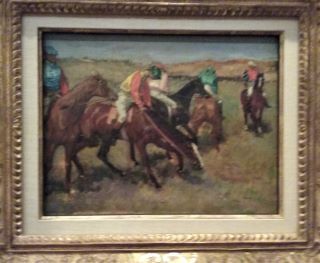

It was at this stage that he became involved with the Impressionist group. He had become disenchanted with the classical, historical style required by The Salon, and instead was fascinated by all aspects of modern life. He was a fixture at the Le Garnier Opera, voraciously painting the opera and ballet there, the back stage life, Paris’ dance halls, cabarets, and cafés and racetracks. He also studied the simple, everyday gestures of working women: milliners, dressmakers, and laundresses. He was drawn to explore movement that was precise and disciplined, such as that of racehorses and ballet dancers, and absorbed a diverse range of influences from Japanese prints to Italian Mannerism.

What techniques do you see in the close-up ballet scene pastels below? Do you agree that he was a master of capturing movement and using bold colour and light to best effect? Do they appeal to you?

Degas was instrumental in organising, and exhibiting in, many of the Impressionist’s break away art shows. He also encouraged Berthe Morisot1 to join the group, which was a very radical thing to do, having a woman join an all-male group. In fact, he often took a high hand in his interactions with the group, making pronouncements about how they should exhibit, and causing dissension, rifts and disunity as a result.

However, despite the close association, he never identified as an Impressionist, but rather, wanted to be known as a Realist or “an Independent”, and openly derided their penchant for painting “en plein air”. Unsurprisingly, he never had much in common with Monet who was a devotee of painting outdoors.

Nevertheless, Degas was very successful as an artist, and earned sufficient income from his work to became a prolific art collector, acquiring thousands of paintings, drawings and prints. This included works of his revered 19th century masters Ingres, Delacroix and Daumier, as well as those of his contemporaries including Manet, Cezanne, Gauguin, Cassatt, Pisarro, and Van Gogh.

Degas was well known to be argumentative, cantankerous and outspoken. In later life, Renoir is quoted as saying of him: "What a creature he was, that Degas! All his friends had to leave him; I was one of the last to go, but even I couldn't stay till the end."4

Yet one of his most enduring friendships, of over 40 years, was with Mary Cassatt2. She was an American artist who made her home in Paris, and she was also a forthright, outspoken person like Degas. They met in 1877, and it seems that in Mary, Edgar had met his intellectual match.

They had a real affinity as they had a lot in common. However, this was not a romantic connection. Both were highly educated, were from well-to-do banking families, and moved in the same social circle. Both had studied in Italy, both were fiercely independent and both never married or had children. Instead, they collaborated closely, and championed and admired each other's work. They were both extremely passionate workers, and challenged each other in experimenting with materials and techniques, especially in Japanese print making4.

Degas was also known to be vociferously anti-Semitic, particularly over the Dreyfus affair, which began in 1894, when the French army falsely accused Alfred Dreyfus, a Jewish officer, of treason. Even though he was later acquitted, the scandal fueled anti-Semitism and tore French society apart. The French artists also were split: Degas, Cezanne and Renoir were staunchly anti-Dreyfus, while others such as Manet and Pissaro were very much supportive of the man. But Degas was typically vocal and therefore much more remembered for his derogatory views.

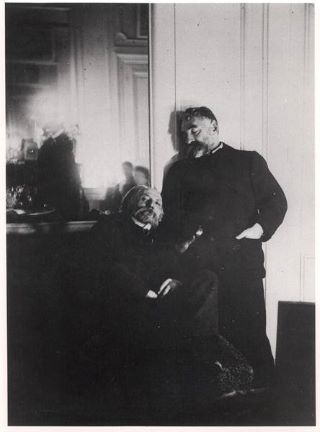

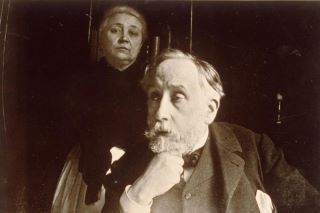

As Degas' eyesight deteriorated, he turned more and more to sculpture and photography, as these were more “forgiving” in preciseness of execution. Below left is one of Julie Manet3 and her cousins, not long after the death of Julie's mother Berthe Morisot1 in 1895, and one of Renoir with Stephen Mallarme, who Berthe Morisot appointed to be the guardian of her daughter Julie after her death.

After Degas' death in 1917, over 150 sculptures made from wax, clay, and plastiline were discovered in his studio. His heirs authorized the casting of his works in bronze so that they could be sold.

Yet only one wax sculpture was ever exhibited during his lifetime, called Little Dancer Aged Fourteen (1878-1881). It is an almost life-sized girl wearing a real dancer’s net costume and a wig of human hair, and was widely criticised as being ugly.

In July 2016 I had the privilege to visit the Degas exhibition at the National Gallery of Victoria, where over 200 paintings, sculptures and sketches were on display. Here are a few of my photos from that exhibition, including that of the Little Dancer.

Degas became more and more isolated as he got older and more visually impaired, and he eventually had to stop working in 1913. He died in Paris in September 1917, aged 83.

Footnotes:

-

If you would like to read our earlier blog on Berthe Morisot, click here.

-

If you would like to read our earlier blog on Mary Cassatt, click here.

-

If you would like to read our earlier blog on Berthe's daughter, Julie Manet, click here.

-

The information has been sourced from Wikipedia and the National Gallery of Victoria (ngv.vic.gov.au.

If you would like to read more detail on Edgar Degas, click here.