Canaletto: Capriccio or Fact?

This lovely scape of Venice (above), created by Canaletto (1697-1768) and titled: Capriccio a Palladian Design for the Rialto Bridge with Buildings at Vicenza contains three Palladian monuments, set next to each other...... but none are actually in Venice!!

In fact one of these buildings doesn’t even exist!

The work can be interpreted as an homage to Andrea Palladio. It shows two works by this important Renaissance architect, as well as a design for the Rialto Bridge in Venice, which never came to fruition. On the right is the Basilica Palladiana in Vicenza which was begun in 1549, one of the earliest works of the then unknown Palladio. The Palazzo Chiericati, which is also located in Vicenza and was completed shortly after the Basilica, is shown on the left edge of the work. The centre of the composition is dominated by Palladio's unrealised design for the Rialto Bridge in Venice. Instead of Palladio's work, a design by the unknown architect Antonio da Ponte was used for this famous bridge, created in 1588. 2

In painting, a capriccio means an architectural fantasy, placing together buildings, archaeological ruins and other architectural elements in fictional and often fantastical combinations. These paintings may also include staffage (figures). Capriccio falls under the more general term of landscape painting. The term is also used for other artworks with an element of fantasy (such as capriccio in music). This style of painting was introduced in the Renaissance and continued into the Baroque period.3

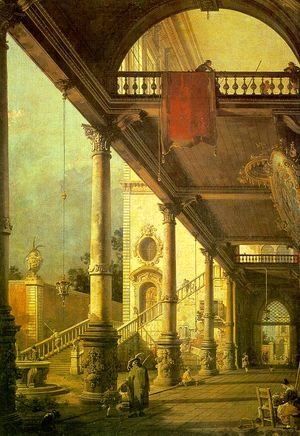

I rather like Canaletto's capriccio, where he juxtaposed the real with the imaginary. The example above is Capriccio of the Scuola di San Marco from the Loggia of the Palazzo Grifalconi Loredan.

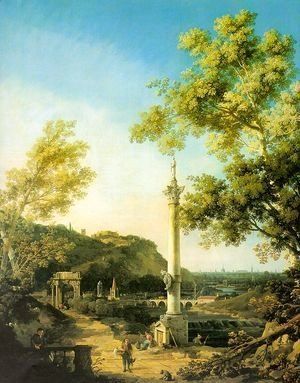

The composition in a capriccio should be, of course, perfect as the artist can use their eye to get the right mix of buildings and other topographical features. In reality, sometimes buildings and other features don't sit right but if painting a capriccio image, the artist is free to move the structures around and to add and subtract in order to achieve the desired composition. And Canaletto did this with aplomb!

Here is a small selection of Canaletto's capriccio. I do recommend you read the captions carefully as they give a detailed description of the content in the painting.

The details in Canaletto's painting are wonderful and he has applied the same style to his capriccio.

And now we will examine one of Canaletto's capriccio to see how he has moved and married existing features into different positions. The capriccio painting of Canaletto's I have chosen is of San Marco (St Mark's Basilica) in Venice, photographic images of which I have given below.

This is Canaletto's capriccio painting showcasing the four horses from San Marco. But note! Canaletto has not only moved the horses but placed them on pedestal!

This explanation of the painting comes from the Royal Collection Trust (UK). I know that it is rather long but some of you will be interested in the details.

When the Venetians took Constantinople in 1204 during the Fourth Crusade, they brought back important artefacts to Venice, including four magnificent gilt-bronze Greek or Roman horses. These were installed above the central arch of the west façade of San Marco, the focal point of Venetian life, as symbols of the power of Venice and Venetian pride. Their removal to Paris by Napoleon in 1798 was therefore devastating; they were eventually returned in 1815.5

Note that Canaletto painted his capriccio of San Marco in 1743 which was 55 years before Napoleon removed the horses.

Canaletto has taken down the horses from San Marco and placed them on high pedestals in front of the Basilica. Among the visitors studying the horses is a group of Procurators and Senators on the right, gazing up at them in awe. The dating takes an unusual form. The nearest pedestal has the Latin inscription, "A B VRB. COND. MCCCXXXII", above and below the Grimani arms under the ducal cap. Pietro Grimani reigned as Doge from June 1741 to March 1752. The inscription states that the date is 1,332 years after the foundation of Venice, which traditionally took place in AD 421. The date of the painting would therefore be 1753, which is after Grimani's death and nine years after the rest of the series. It has been plausibly suggested that Canaletto added a third X in error, which would make the date 1743. If this X was intended to be a I, the date would be 1744, which matches the date of the rest of the paintings in this series of 13 overdoors commissioned from Canaletto by Consul Joseph Smith. This use of the date of the foundation of Venice both emphasises the signifiance of the horses and links the Venetian Republic with ancient Rome.5

The bas-reliefs on the two inner pedestals probably allude to the taking of Constantinople in 1204. Not only are the horses ancient Greek or Roman, but they have always been associated with Roman triumphal arches. The central entrance to San Marco architecturally forms its own triumphal arch, so here the horses symbolised the invincibility of Venice, powerful successor of the Roman Empire. When they were moved to Paris they were eventually placed on the Arc du Carrousel, which honoured Napoleon's triumphs.5

Perhaps Canaletto's removal of the horses from their position of honour had a deeper and more politically significant meaning, undermining the myth that Venice was the legitimate successor of Rome. Yet their arrangement in the Piazza had the advantage of allowing the horses to be presented and admired as works of art. Consul Smith may have known Enea Vico's publication Discorsi sopra le medalglie de gli antichi (Venice 1555), in which the author suggests giving the horses more space and dignity by moving them to high pedestals in beautiful marble in the Piazza. Smith would certainly have known Anton Maria Zanetti's two-volume publication in 1740, Delle antiche statue grecche e romane, since he obtained the rights to publish the book. Here each horse was given its own plate, reproduced in careful detail. Thus both Canaletto and Zanetti were concurrently awarding these bronzes the status of individual works of art.5

There can be no doubt Canaletto was a remarkable and highly skilled artist. So to conclude our short course on Canaletto, tomorrow we are going to look at some of his drawings and etchings. His expertise in being able to execute the exact dash of colour and the perfect placement of a stroke of a line stems from his formidable skill with a pencil!

Credits

- canalettogallery.org

- lempertz.com

- en.wikipedia.org

- commons.wikimedia.org

- rct.uk

- archeology-travel.com