The Remarkable Community of St Kilda

From the moment we approached the island of Hirta in the St Kilda archipelago off the north-west coast of Scotland in the Outer Hebrides, Scotland it seemed shrouded in mystery as the clouds hung heavy over this tiny patch of land which is steeped in a remarkable historic narrative. In fact the story of St Kilda has attracted artistic interpretations, including Michael Powell's film The Edge of the World.

In the St Kilda archipelago the largest island is Hirta 670 hectares (1,700 acres) and whose sea cliffs are the highest in the United Kingdom. There are three other islands (Dùn, Soay and Boreray) in the archipelago which weren't inhabited but were also used for grazing and seabird hunting by the people who lived on Hirta.1

When you look at the image above I am sure you are wondering what on earth are the rocky mounds dotted around the landscape. Surely they can't be rocks all of the same shape and size? No - these structures are definitely not natural but man made features called cleitean. A cleit is a stone storage hut or bothy - a structure which is unique to the island of Hirta.1

In the middle ground (above) you can also see some of the restored cottages from the original village, some of which are now used by the visiting conservationists, volunteers and scientists.

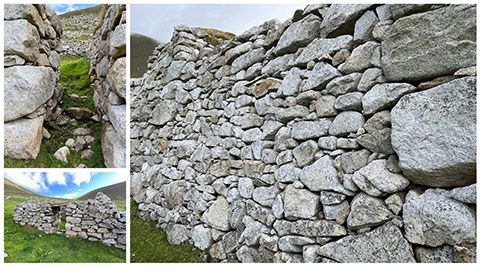

As you can also see this is a very rocky landscape and I was fascinated by the intricate stone work employed to create the buildings and protective fences using the drystone technique which is almost as old as the human race! Some dry stone wall constructions in north-west Europe have been dated back to the Neolithic Age.1

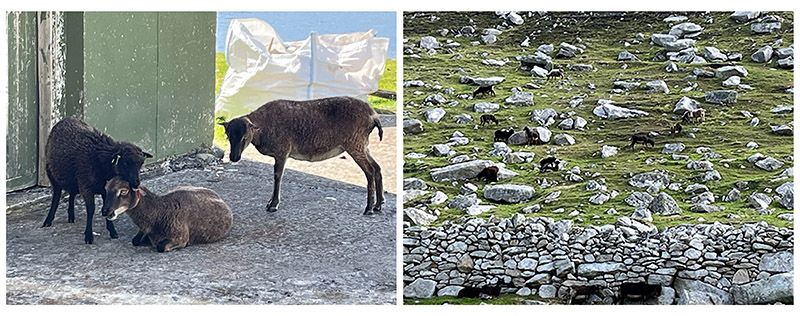

This tiny isolated self-sufficient community kept sheep and a few cattle and also grew crops such as barley and potatoes on the better-drained land in Village Bay. 1

Also shown in the image below is the Feather Store (on the edge of Village Bay), where the feathers from the Fulmar and Gannet birds were stored and sold to pay the rent to the MacLeods of Harris, whose steward was responsible for the collection of rents in kind and other duties as this land was part of the MacLeods' domain.1

The Soay sheep on Hirta also merit recognition, that is, apart from being very nimble of foot as they negotiate the incredibly rocky terrain. This breed is physically very similar to the wild ancestors of domestic sheep and are considered to be a direct descendant of the moufflon found in Sardinia and Corsica.1

I am sure you are beginning to understand how harsh a life it was to live on Hirta. But the most courageous acts these people performed - apart from surviving the appalling weather conditions and being cut off from the rest of the world - was that part of their main diet was to eat the local seabirds and their eggs. They ate the flesh and eggs of razorbills, fulmars, guillemots, gannets, puffins, great auks (before they were driven to extinction in the mid-19th century) and shearwaters.2

To capture the birds and retrieve the eggs the villages had to scale down the steepest cliff faces in the United Kingdom on the end of a rope! And you might have noticed that there are no trees in this landscape. This is because the winds are so strong that no trees grow on this land!

Why didn't they eat fish I hear you ask? Afterall they were surrounded by water. I too wondered this until I read that the waters are so treacherous and the storms so bad that the boats these people could make would never have survived.

A 250-year-old census has revealed St Kilda islanders ate more than 1,600 seabirds every day. The census lists 90 people living on the main island of Hirta on 15 June 1764 – 38 males and 52 females, including 19 families and nine individuals. Further light is shed on the islanders’ diet, with each resident said to eat “36 wild fouls eggs and 18 fouls” daily – an island-wide total of 3,240 eggs and 1,620 birds every day.3

Climbing seemed to figure largely in this community especially for the young men as an important island tradition involved the 'Mistress Stone', a door-shaped opening in the rocks northwest of Ruival over-hanging a gully. Young men of the island had to undertake a ritual there to prove themselves on the crags and worthy of taking a wife!1

The tiny community on Hirta did have occasional visitors which in most cases caused more harm than good. Visiting ships in the 18th century brought cholera and smallpox and in 1727 the loss of life was so high that there were not enough men to man the boats and new families were brought in from Harris to replace them.By 1758 the population had risen to 88 and reached just under 100 by the end of the century. This figure remained fairly constant from the 18th century on until 1851 when 36 islanders emigrated to Australia on board the Priscilla, a loss from which the island never fully recovered.1 Tragically, more than half this little band of immigrants died on the way to a new life due to the fact that they had no immunity from diseases.

Religion did come to the island first in 1705 when a missionary called Alexander Buchan arrived but didn't seem to make much of an impact. Then the Rev John MacDonald, the 'Apostle of the North' arrived in 1822. He set about his mission with zeal...returned regularly and fund-raised on behalf of the St Kildans, although privately he was appalled by their lack of religious knowledge. The islanders took to him with enthusiasm and wept when he left for the last time eight years later.1

In 1830 the Rev Neil Mackenzie, a resident Church of Scotland minister did manage to improve the conditions of the inhabitants. He re-organised island agriculture, was instrumental in the rebuilding of the village and supervised the building of a new church and manse. With help from the Gaelic School Society, MacKenzie and his wife introduced formal education to Hirta, beginning a daily school to teach reading, writing and arithmetic and a Sunday school for religious education.1

Mackenzie left in 1844 and although he had clearly achieved a great deal, the weakness of the St Kildan's dependence on an external authority was exposed in 1865 with the arrival of Rev John Mackay, a minister in the new Free Church of Scotland. Mackay was a religious zealot who may have done more than any single individual to destroy the St Kildan way of life. He introduced a routine of three two to three-hour services on Sunday at which attendance was effectively compulsory.1

The excessive time spent in religious gatherings began to interfere seriously with the practical routines of running the island. Old ladies and children who made a noise in church were lectured at length and warned of the dire punishments they could expect in the afterworld. During a period of food shortages on the island a relief vessel arrived on a Saturday only to be informed by the minister that the islanders had to spend the day preparing for church on the Sabbath and it was Monday before any supplies were landed. Children were forbidden to play games and required to carry a bible wherever they went. The St Kildans endured Mackay for twenty four years.1

Tourism had a different but similarly de-stabilising impact on St Kilda. During the 19th century steamers began to visit Hirta, enabling the islanders to earn money from the sale of tweeds and bird's eggs but at the expense of their self-esteem as the tourists clearly regarded them as curiosities. The boats also brought other previously unknown diseases, especially tetanus infantum which resulted in infant mortality rates as high as 80% during the late nineteenth century.The cnatan na gall or boat-cough became a regular feature of life.1

By the turn of the 20th century formal schooling had become a feature of the islands and in 1906 the church was extended to make a schoolhouse. The children all now learned English in addition to their native Gaelic. Improved midwifery skills, denied to the island by Reverend Mackay, reduced the problems of childhood tetanus. There had been some talk of an evacuation in 1875 during MacKay's period of tenure, but despite occasional food shortages and flu epidemic in 1913 the population was stable at between 75 and 80 and there was no obvious sign that within a few years the millennia old occupation of the island was to end.1

During WWI on 15 May 1918 an SM U-90 submarine surfaced unexpectedly by Hirta...Its 80 inhabitants were warned politely that shelling was imminent and their village was duly bombarded. No islander was harmed. Despite the brevity of hostilities, the First World War was fatal for St Kilda’s culture. The sense of a ‘shrinking world’ became inescapable and the few island’s youth migrated to the mainland...4.

Without the help of these young men and a growing realisation that the lack of medical care was causing unnecessary deaths in May 1930 the islanders decided to leave and with government assistance were resettled on the mainland of Scotland.

The plaques noting those who lived in the homes on the island are a poignant reminder of a past time and a very different life for the tiny community who lived on Hirta in the St Kilda archipelago.

The archipelago is owned by the National Trust for Scotland and is a World Heritage Site for both natural ecological and archaeological significance. St Kilda achieved World Heritage status for its outstanding natural heritage and was among the very first sites put forward by the UK for inscription on the World Heritage List in 1986. In 2004, the inscription was extended to include the surrounding marine environment and in 2005 the archipelago became the UK’s first and only mixed World Heritage Site, and one of only 35 worldwide when the islands’ relict cultural landscape was also inscribed on the World Heritage List.5

The island of Hirta is now made more remarkable by the melding of the new world with the ancient. The Ministry of Defence (MoD) have been operating a year round station on Hirta since 1957. In 2020 a new Accommodation Block and Energy Centre was built on the island at the edge of the world. As shown below this facility blends in unobtrusively with the landscape and sits comfortably next to the cliet on the right hand side in the image.

Currently, the only year-round residents on Hirta apart from military personnel are a variety of conservation workers, volunteers and scientists who spend time there in the summer months.1

In a few days I will conclude my cruise around the Scottish islands with a post on the equally remarkable island of Iona where St Columba founded a monastic community back in 563 followed by one last look at the remarkable cliffs of the Scottish coast!!

Credits

1. en.wikipedia.org

2. geographical.co.uk

3. theguardian.com/uk-news/2016/dec/29/1764-census-reveals-st-kilda-residents-feasted-on-1600-seabirds-a-day

4. hoddereducation.co.uk/

5. hbarchitects.co.uk/st-kilda-accommodation-block-and-energy-centre