Preserving the art of traditional Japanese woodcraft – Part 2

Today we are going to meet an artist with a difference!

Des King is a former Australian Army officer, who first came into contact with the Japanese culture when he was selected to attend a 12-month intensive Japanese language course at the RAAF School of Languages at Point Cook (now the Australian Defence Force School of Languages, Laverton) in 1974. In 1978 he was sent to Japan by the Australian Army for advanced Japanese language studies, consisting of one year at the United States Department of State Foreign Service Institute in Yokohama, and one year in the Office of the Military Attaché at the Australian Embassy, Tokyo. It was here that he met his wife Mariko, who he describes as ”my soulmate and biggest supporter.” 1

He left the Army at the end of 1986, eventually moving to Tokyo to live and work with his wife, Mariko, as a free-lance Japanese-English translator. 1

After 20 years of translation work, a change was needed, and in April 2008 Des King began a 12-month postgraduate course in construction and architecture at the International College of Craft and Art (Shokugei Gakuin) in Toyama, Japan. The course was entirely in Japanese, and comprised mostly practical work. 1

He concentrated on the traditional Japanese trade of tategu, which is essentially the production and fitting of doors and windows, especially shoji (sliding doors). After building the foundation in making and fitting glass doors and windows and shoji, he turned his focus to the elaborate patterns that can be made by kumiko within shoji. 1

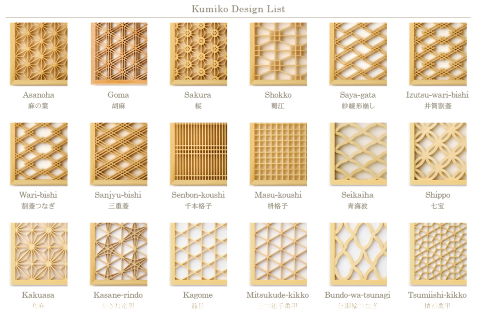

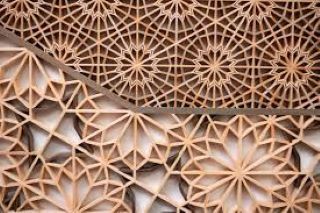

Kumiko is a Japanese technique of assembling wooden pieces without the use of nails. Thinly slit wooden pieces are grooved, punched and mortised, and then fitted individually using a plane, saw, chisel and other tools to make fine adjustments. The technique was developed in Japan in the Asuka Era (600-700 AD). 2

Kumiko panels slot together and remain in place through pressure alone and that pressure is achieved through meticulous calculating, cutting, and arranging. The end result is a complex pattern that is used primarily in the creation of shoji doors and screens. 2

The designs for kumiko pieces aren't chosen randomly. Many of the nearly 200 patterns used today have been around since the Edo era (1603–1868). Each design has a meaning or is mimicking a pattern in nature that is thought to be a good omen. The patterns are designed to look good, but also to distribute light and wind in a calming and beautiful way. 2

Kumiko has now become the central theme of Des’ work.

He completed the course in March 2009, and after extensive discussion, he and Mariko decided to return to Australia and set up a workshop in the Gold Coast, Queensland.

The world of kumiko craftsmen (and craftswomen) is one of secrecy, with new methods and techniques jealously guarded and handed down only within the family or business. Very little is written about how to make the various kumiko patterns. Much of this highly detailed work requires specialist tools not readily available to woodworkers outside of Japan.

While Des King has many of these tools, he has made it his mission to devise methods and design jigs that would enable all woodworkers to make these intricate Kumiko patterns using a normal set of hand tools found in any home workshop.

Des has now written a number of articles, books and e-books on Shoji and Kumiko Design, all with the aim of preserving and fostering Japanese woodcraft.

He spends most of his time these days running one-on-one Kumiko classes in his workshop on the Gold Coast in Queensland.

Footnotes

- With thanks to Des King, Queensland via kskdesigns.com.au

- With thanks to Wikipedia