"My Meeting with Nadine de Koenigswarter" by Hannah Starman

The following article was written by Hannah Starman, who holds a PhD in International Politics and is frequently called upon to consult with government bodies and agencies. Hannah also has a passion for art.

Here she interviews the French artist Nadine de Koenigswarter for whom music is an important influence. Nadine is the great niece of Nica Koenigwarter, who was totally immersed in the jazz scene of the 1920s, 30s and 40s and wrote a book (which Nadine edited) called The jazz musicians and their three wishes,1 which faithfully records photos and interviews with many famous musicians over a number of years. A film called Bird was made about Nica by Clint Eastwood. Apart from this deep family influence, Nadine herself has spent much time amongst African musicians and their influence pervades her art.

This article was published in the Swiss arts magazine Arteez in July 2021 and explores the way the family history and Nadine's own experiences have influenced her. It is translated and reproduced here with permission.©

Nadine de Koenigswarter received us in her studio which she set up in her house near Paris, surrounded by her rescue dogs, her art works, books and an impressive collection of vinyl records. The artist was participating in the collective exhibition Portrait, self-portrait, at the Jenisch Museum in Vevey, Switzerland, in 2021 (which anArt4Life has featured in a previous post here.

Nadine de Koenigswarter spoke to Hannah Starman about her artistic work, jazz, West Africa and of her passion for living.

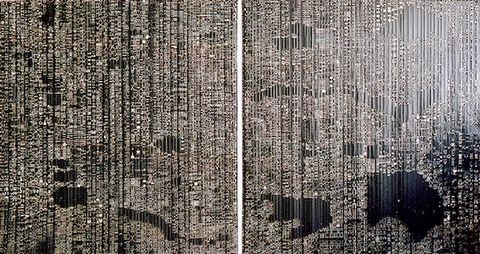

Hannah Starman for Arteez: You are presenting two large drawings from the Dreams series at the “Portrait, self-portrait” exhibition in Vevey. Where does the inspiration come from to draw these “powerful, fragile and hieratic” women as you describe them? Is it a portrait or a self-portrait?

Nadine de Koenigswarter (NDK): I fully subscribe to the exhibition curator, Frédéric Pajak's vision that there is a part of a self-portrait in each portrait. There is a projection, but it is also completely mixed up. It's not me, but it's also definitely me. I have always been attentive to dreams and to this inner universe that lives within us. This figure of a powerful woman appeared to me in dreams, waking dreams, and interior visions with very strong images of which Georges Bataille (the French philosopher) speaks. This has happened to me two or three times in my life, for example, following the disappearance of my cousin, to whom I was very close.

I started this series of Dreams (in French Songes) one evening after suffering creative block for several weeks. At the time, I was doing a lot of abstract work and in abstraction, things are not said in the same way. The first drawing of a strong woman who was unable to express herself seemed obvious to me. The two dreams drawings that are in Vevey have also sprung up quite spontaneously. In addition, there is no possibility of forgiveness, of a second chance because it is ink. These drawings have a certain naivety, an expression at the crossroads of dream and reality. But it's true that during the work, I don't care about "beautiful or not beautiful", but rather to feel if what I'm doing is "alive or dead". It is always these two elements that for me determine whether a work holds up or not.

You are self-taught with an atypical background. How did you become the artist you are today?

NDK: As a young self taught artist I had no friends of my generation who were artists. I was also coming out of a difficult adolescence. I started to paint and draw hoping to create the confidence to express myself through a language that was not made of words that scared me. I was withdrawn, mute, and I hid from showing any form of exterior. I had no self-confidence and no benchmarks. Self-belief was built little by little, painting helped me a lot, but it's difficult to move forward without a school and without a reference. I had done a year at the Penningen studio but the school trained in illustration and that was not what I wanted. I got fired (she laughs).

Then I met an older artist of Romanian origin, Julian Mereuta, a political refugee in France, who offered to set me up for a while in a corner of his studio, a simple room in Bagnolet. I also met Wolf Vostell, an extraordinary artist, from the Fluxus generation, who died at 60, too young to leave. He was close to Nam June Paik, John Cage and all those artists. He told me: take whatever comes. Take the profusion, take the excess, take everything. From that moment, I told myself that I would do what I want to do. One day, I did a stain on a drawing and I said to myself: This is where there is life. This is what is alive. I think that's what triggered this need for more abstract work for a long time.

Your work is very varied. There are abstracts, drawings, photographs, multiples, light boxes, and writing too. How do you work? Were there periods during which you opted for one form of expression rather than another?

NDK: No, there is no chronology in my work. I can start something in one form of expressioin at a certain time and resume this work after 20, 25 weeks or later. It's true that I was creating in abstract for a long time but I go back and forth all the time using different forms of expression, without it causing me any problem. For example, the Dream with a Double Head appeared to me when I lived in New York and at that time I made a small engraving of it. I took it up again much later to do the large format drawing which is presented in Vevey. I love engraving even though I hardly ever did it, but in all the work I do now I revolve around engraving. For the series of dogs (Fabulous dogs, fabulous dogs), I scraped, I removed, I worked in reserve. Even when I was doing abstract work, I always wanted to find the layer before, the one below, until I found the background, the canvas. I don't like style effects, it has to be very simple.

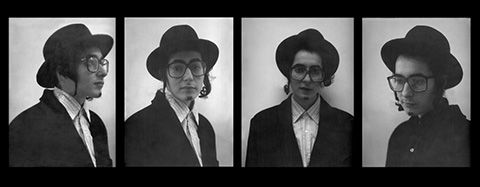

Sometimes I also do things for fun, around the family, like this self-portrait dressed as a rabbi. I was coming back from Prague because my family is more or less from there and I said to my father, Dad, I'm telling you that we have an Orthodox cousin that I met in Prague and that he authorized me to take pictures of him here. My father never recognized me (laughs). I don't feel good in a work that is too monolithic or that goes in the same direction. I need variations that stimulate my desire to explore and create. It's so jubilant!

Music has played an important role in your life, work and family. Pannonica (Nica) of Koenigswarter has dedicated her life to jazz and New York jazz musicians. You yourself lived for a long time in New York with Charles Gayle, a major figure in free jazz. Who was Pannonica for you and how much did her love of jazz influence you?

NDK: My grandmother died at 20 giving birth to my father. My grandfather, Jules de Koenigswarter, who was widowed, very quickly married a distant cousin, Pannonica de Rothschild, and they had five children together. She is therefore not my direct grandmother. She lived in New York and we didn't have much contact with her. On the other hand, his children lived with us in Paris. My grandfather, a diplomat who travelled often, had decided that the children would be better educated in France and my father welcomed the siblings to his private mansion. Pannonica left her mark because I was very attracted to jazz. Then, I lived for ten years in Africa and it was a desire for Africa and nothing else. There was really an attraction for it. I don't know if it's related, but maybe Interstellar space, Rashied Ali, or Steve Lacy, a charming musician who died prematurely still influence me. His game was quite mental, intellectual, but magnificent. When I work, I like to listen to music that transports me, that isn't too melodic or romantic, that doesn't put me in a particular state of mind. Free jazz, precisely.

The second face on the large Songes (Dreams) drawing resembles Pannonica.

NDK: You are not the first person to tell me this. It wasn't intentional, but it was pointed out to me. It's true that when I do a job like that, I let myself be guided by what I feel. It's not always conscious. It wasn't her that I wanted to do in particular.

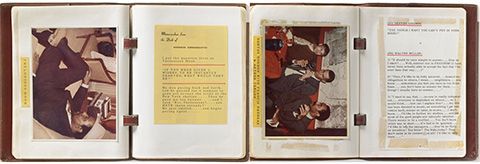

You edited, with Frédéric Pajak (the exhibition curator) the photos of musicians and their three wishes collected by Pannonica for her book, "Jazz musicians and their three wishes". How did this project get started?

NDK: I lived for a while in Pannonica's house in New Jersey after her death. I slept and worked in her room. One day, I came across a large trunk full of polaroids that were fading and disappearing, the polaroid being very fragile if it is not fixed. There were pictures of John Coltrane, Miles Davis and lesser known people. I knew the only way to save those photos was to scan them. I brought everything to Paris and showed the photos to Frédéric Pajak. We agreed on the fact that it was necessary to make a work as true as possible and not necessarily a beautiful book.

The musicians' wishes, typewritten, and the photos were pasted into Pannonica's leather Hermès notebooks. These notebooks were, following publication, exhibited at the Maison Hermès in New York and Bern and at the Jazz Festival in Montreux. It was beautiful because she had pasted these photos with old tape that had rubbed off on the other side. Pannonica's house remains at the disposal of the musicians who still live there, some older than the others. At the time, there was Richard Wilkinson, June Tyson's husband, who was Sun Ra's favorite singer. He knew all the people of that generation. We spent about ten days together identifying the musicians in the photos and a month later he died. This book is particularly important because it is a sociology of the jazz of the time. Even if sometimes the wishes are not very original, it reflects the hopes of the musicians, whose music we mainly knew. Pannonica opened the door into their lives and she very much wanted the book to be published.

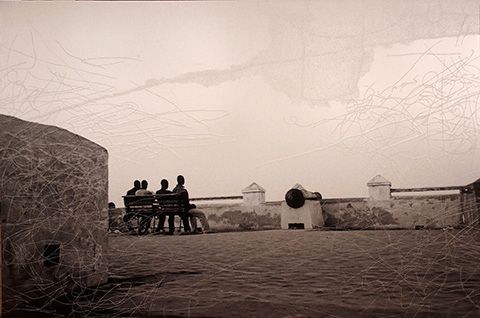

You lived and traveled in West Africa with a group of musicians for several years. What attracted you there?

NDK: I was fed up with Parisianism, but it was really also a need for Africa. There was no other continent that made me want to go and live there and it's true that it was quite brutal. I was a part-time visual arts teacher in a school in Paris. I had already visited Dakar and initially wanted to go back there to work with street children. Some well-known artists, for example Ousmane Sow, and lesser known ones, were already doing this. Ultimately, that part didn't happen. In 2000, I was invited by the sculptor Alain Kirili to attend for about twenty days a meeting in Dogon country in Mali with the community of Dogon and Awa and African-American musicians like Joseph Jarman or Leroy Jenkins . A fabulous experience. Two years later, I returned to Africa and went to the Saint Louis Jazz Festival in Senegal. I met traditional musicians there and lived with them for almost eight years. They were Guineans, about forty men who lived more or less in a community, a bit nomadic, on adventure as they say. They were economic refugees in Senegal and extremely destitute. They made their own beautiful traditional instruments and played most of the time for local ceremonies.

How has this African experience influenced your work?

NDK: All those black pieces (black pieces & cosmogonies) that I did are very much linked to Africa. In Dogon country, I slept on the edge of the Bandiagara cliff, on a mat on the ground, with the entire starry vault above, all the more present since there is no electricity. I use glossy black paper on the surface and white on the back. I worked blind and I pushed the paper forward from the back. This causes the white to burst and come back forward. This gives large papers that float freely on the wall. When creating I go into the music that often accompanies me when I work, like in a trance, and I let myself be guided by the rhythm, more than by the visual. It's a pulsation, it's an impulse. It is the rhythm of the kora, the African harp, which makes me be embraced by the rhythm. I work on the ground and it's blind work and without prior intention. I like it when one job leads to another. Like something endless but with a purpose which is to find a state of balance/ imbalance that suits me. I can stop the work at this stage, but sometimes it takes longer to know if it holds up. I took a lot of photos in Africa, films too, about my Guinean friends, about this community. I also drew a lot of these musicians from life. I filled about thirty notebooks there. I drew them all the time. It was also a way for me to interact with people. I drew children, families and I gave them the drawings.

What projects or artistic forms would you like to explore?

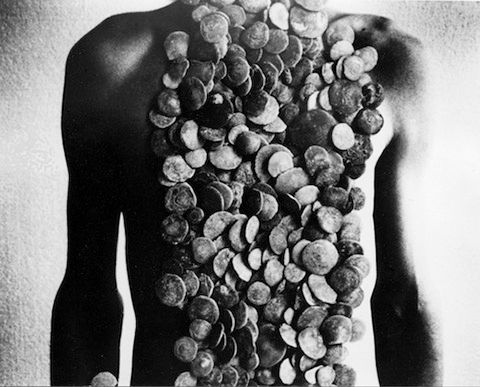

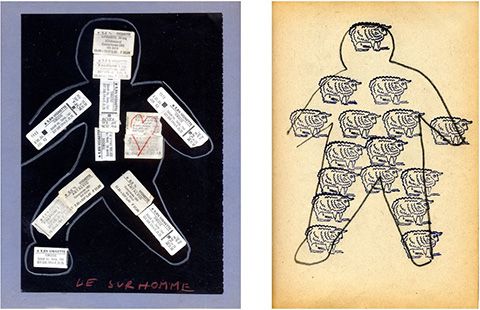

NDK: I've been working on a book about one of my cousins, Philippe Lunel, who died of AIDS in 1994 and who was very close to me, for fifteen years. I have always painted and drawn but when I wrote the book about my cousin, it was a difficult, reflective, painful immersion, but on the other hand, writing and finding the words was exhilarating. The words, the precision of the words, it was another pleasure that I discovered. It will be a book full of images because we had an almost daily exchange for ten years before his death.

We exchanged objects, drawings, letters and I made a collection of all that. Also, I made a few mixed media works based on my interactions with him. I made about ten by hand and called them Insomnia. My cousin was an insomniac and he had sent me a drawing of a man he had called The Superman, surrounded by the names of drugs for anxiety or for sleeping, with terrible names such as, Urbanil, Palfium, Temgesic. In reply, I had sent him a man who counts sheep. This project is very close to my heart and the book will be released one day, I hope.

© A very special thank you to Hannah Starman and the editor of the Swiss art magazine Arteez who have given their permission for the article to be translated and reproduced here on the AnArt4Life blog.

Please follow this link to read more art articles on the ARTEEZ website.

Late Mail

A special welcome to I.G. in Australia who has just joined up to the AnArt4Life blog. We do hope you enjoy this journey with us where we share art around the world.

Credit

1. Note: An English-language version was published in 2008 as Three Wishes:An Intimate Look at Jazz Greats.