Portrait, self-portrait by Hannah Starman

The following article was written by Hannah Starman and published in the Swiss arts magazine Arteez1 in June 2021. It is reproduced here with permission.©

The article features an interview conducted by Hannah Starman with two exhibition curators and five artists.

The exhibition Portrait, self-portrait, presented at the Jenisch Museum in Vevey (Switzland) brings together 212 works by 106 artists around a unique project of art and friendship. The curator of the exhibition, Frédéric Pajak, the curator of Fine arts, Emmanuelle Neukomm and the artists Nadine de Koenigswarter, Sylvie Fajfrowska, Jean-Baptiste Sécheret, Joël Person and Tobias Eugster tell us about this powerful and enchanting exhibition.

Hannah Starman for Arteez: How did this portrait and self-portrait exhibition project come about?

Emmanuelle Neukomm: In 2018, Frédéric Pajak commissioned the exhibition “Poetic drawing, political drawing” at the Jenisch Museum. We find some artists for this new hanging. There is a very important dimension of friendship in Frédéric's approach and it's wonderful to be able to promote artists of such quality. One day, Frédéric told us about his desire to set up a project around portraits and self-portraits. It was an important question for him, the notion of autobiography is already central in his work. Knowing the man and his culture, we were immediately won over by the idea. The Jenisch Museum is the custodian of a rich heritage of more than 45,000 prints and drawings. This new collaboration offered a great opportunity to promote these funds.

Frédéric Pajak: We could have a large exhibition on the great portraits of the history of painting: La Joconde, Les Méninesor an exhibition on the large portraits of Rembrandt, very "flashy" in which the public would find themselves easily since these large paintings are part of our genes. But it wouldn't have the same impact as an exhibition with more personal works. There is something intimate about drawing for me and often these are drawings that we hide. As a drawing editor, I see thousands of them every year. Often I discover drawings that are in boxes, which the family never wanted to show. There are artist's notebooks and this is really a feature of the exhibition. These images are unfamiliar, so we have to go and find them.

Emmanuelle Neukomm: The exhibition does not seek to hold a great scientific discourse on the variety of the genre of portraiture, self-portrait, not at all. Rather, it is a stroll, a pleasure, Frédéric's gaze, his choices, which appealed to him and the visitor strolls according to the encounters he will have with the picture rails. As soon as you enter a room, you have dozens of pairs of eyes that are on you. You almost reverse the roles and it is the spectator who becomes the object. There is certainly life here at night (laughs).

The exhibition is presented in two central rooms and four cabinets. How did you design the hanging to allow dialogue between such varied works?

Emmanuelle Neukomm: Frédéric gave us few instructions. We had to have Nadine de Koenigswarter and Kiki Smith in the center, because it's very strong when the doors are open and we wanted to bring together the mortuary portraits and the animal portraits. In the central rooms, there is mainly contemporary art and in the small cabinets modern art. For the rest, we had a lot of freedom, which is both an opportunity and a challenge. There are things that were necessary, connections that also worked in the publication. But these successes on paper cannot always be transposed to the walls. We have built a hanging where things answer each other, where they communicate visually, where they question. Suddenly, we can go from an Otto Dix to a Noyau (Yves Nussbaum) or to a Kiki Smith. The theme allows us great differences. A portrait can be barely sketched or extremely meticulous. It can be the size of a postage stamp or a large format like those of Nadine from Koenigswarter. It can be ceremonial, rather official or extremely intimate. It can be a mortuary portrait or the expression of an overflowing vitality. The portrait and the self-portrait offer a diversity and a truly stimulating richness and Frédéric has this formidable capacity to create links between artists of different periods. It can be a mortuary portrait or the expression of an overflowing vitality. The portrait and the self-portrait offer a diversity and a truly stimulating richness and Frédéric has this formidable capacity to create links between artists of different periods. It can be a mortuary portrait or the expression of an overflowing vitality. The portrait and the self-portrait offer a diversity and a truly stimulating richness and Frédéric has this formidable capacity to create links between artists of different periods.

Frédéric Pajak: When you do a display of this type or when you have such a large choice of works, there are invisible links between things. I started with the catalog and then I tried to find some logic that is arbitrary, but it exists. I gave directions for hanging up. I wanted the first impression when you walk into this exhibition to be contemporary drawings, not "old stuff." But I wanted the small rooms to reflect on older things. I didn't want to give the feeling of making a story of the drawing. It was the links that mattered. I knew, for example, that there were going to be Hodler's drawings of Valentine's agony. When I saw this drawing at my brother's funeral, which was done by a friend of his (Tobias Eugster), I found it resonated very well with others. There are invisible threads between these works and they come together spontaneously.

Tobias Eugster: We told Bobo (Boris Pajak, brother of Frédéric) that he had six months to live. He wanted to make the trip to India with his sons and I accompanied them there. The trip went very well until the last day when he suddenly fell very ill. He lost consciousness and was hospitalized in Biel. When I got to the hospital, he had just passed away. I asked the hospital secretary to give me a sheet and a pencil so that I could draw my friend. It is as if I had stroked him one last time.

Certain subjects are indeed loaded with meaning such as illness, death….

Joël Person: When I drew my dying father from life, it was a way for me to interact with him. Frédéric chose two drawings from this series for the exhibition. I was 18 when I did the first one (My dad after his brain cancer surgery). My father had just had brain surgery, he had cancer. His head had been shaved, but he was still about normal physically. The second drawing (My father weakened by illness) is done a year later and there he was very thin. At the top of the drawing, we see him watching television or reading and at the bottom, we see that he is falling asleep. At the same time as I drew my dying father, I drew in the Jardin des Plantes animals devouring meat with an eager gaze. I called this series Life Lines. This link was unconscious. (Find our article for the month of May 2021: In Joël Person's studio ).

Emmanuelle Neukomm: The drawings of Joël Person who drew his dying father are echoed here with Valentine Godé-Darel. Hodler met this divorced Frenchwoman - it was already a little sulfurous for the time - in 1908. She was first his model but very quickly they will experience a real passion with heartbreak and reunion. They had a daughter, Paulette. Valentine will fall ill with cancer and throughout her illness, Hodler will assist her physically, going every day from Geneva to Vevey. But he will also accompany it through a cycle of drawings and paintings, producing more than 200 pieces. We can see it over the leaves shrink, also sag. When we see a loved one pass away, the grieving process begins because we know the end is inevitable. But for Hodler, In any case, there is also an artistic issue: nobody has ever done that. It is the first time in the history of art that there is such monitoring of the disease over several months. There is an ambiguity in accompanying a loved one who is leaving, a grieving process initiated and at the same time, apprehending it as an object. It's troubling. He'll even sculpt Valentine to try and hold her back, but he'll never be satisfied.

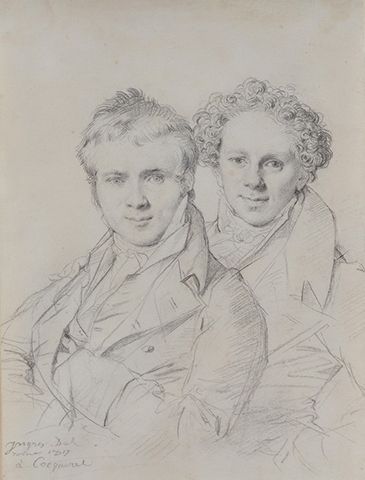

Frédéric Pajak: Each drawing of a sick or deceased person tells a story. For example, in the drawing of Varlin and Dürenmatt, it was a joke between them. They had promised each other that the first to die would be drawn by the survivor. The designs almost have a cartoonish side to them. Each time, it is a very unique expression of illness or death, but which responds to the other. For example, the woman who is just above my brother (Portrait of Benoît Agnès Trioson on her deathbed by Girodet) is dead, but it really looks like the gaze of someone who is still alive. My brother has his eyes closed but he smiles, he has a beautiful expression. I have always liked the drawing of my father (Jacque Pajak) Baga. It was on the wall at my mother's house and I have always had a real passion for this drawing and for Robert Pinget's book, which I have read several times and which I find fantastic. Pinget was Samuel Beckett's secretary and Beckett was James Joyce's secretary. There is a whole lineage here. Moreover, there is this drawing by Robert Pinget and further on there are drawings of Joyce by Wilhelm Gimmi. This is what I mean by invisible links. There is always something being built in spite of me.

How was the choice of works made?

Frédéric Pajak: I don't necessarily try to show works that I find beautiful or that would be according to my taste. Often, I am captivated by a work because I find it unique, because I find it unrecognized. Take for example this portrait of the woman with her little girl and her poodles (Baronne d'Orville van der Hoop, of her daughter and their three dogs , by Xavier de Poret). It is a drawing that is so at odds with others that it illuminates others in a certain way. It was done carefully after nature. It is not a drawing from a photograph. In addition, there is a virtuosity in it. I met the son of this painter who posed for the arms of the little girl. I did not know that this painter was as contemporary as that.

Works always teach us something. What appeals to me is the particular interest of a drawing compared to others. There are drawings that I find very classic, very well drawn, where the face is very well rendered, as with Ingres, for example. Next to it, there is a drawing by Lugardon who was his pupil, much softer but which is of interest because it is a bit hazy. It looks like a drawing by Ingres, but if we approach, we see that it is not a drawing by Ingres, who is much more nervous. In this exhibition, there are a lot of techniques. There are drawings on canvas by Nadine de Koenigswarter, there are large pastel drawings by Sylvie Fajfrowska, there are drawings on Nepalese paper by Kiki Smith. It's good to also show contemporary or modern artists, like Warhol, Giacometti, etc., people that everyone knows. But I also like showing strangers. What is interesting is to show these characters looking at us and we try to get away from who drew the drawing. We see if we like it, if it speaks to us. Often, a portrait grabs us. We cannot have this rendering in a photograph.

“A photograph only captures a brief moment, while the work of the designer is to appropriate the face and make it his own face. This is why the exhibition is called “Portrait, autoportrait. There is this appropriation of the face of the other. "

Frédéric Pajak

As an artist, how did you come up with the works to exhibit?

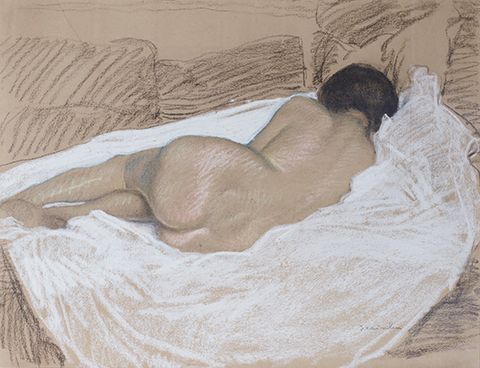

Sylvie Fajfrowska: Frédéric told me about this project but it was imperative to propose drawings. I had painted self-portraits but it had been years since I had done dry pastels. I said to myself: "why not give it a try and participate in this exhibition in Vevey?" »I draw a lot, but they are preparatory drawings and always in a small square format. Concentrating on the drawing and in addition to making a self-portrait in a large format was, for me, a real challenge, but I am very happy to have taken it. I spent the whole month of August 2020 making self-portrait attempts and then I made self-portraits that I was finally happy with. I made dry pastels on paper mounted on canvas and I was happy to achieve something on this very beautiful support. Frédéric pushed me a bit at the start and I'm so delighted that I decided to spend my August doing self-portraits. This year, I will be doing self-portraits which will be conversations with myself in front of an object, double self-portraits. The idea being that the spectator also participates in this exchange.

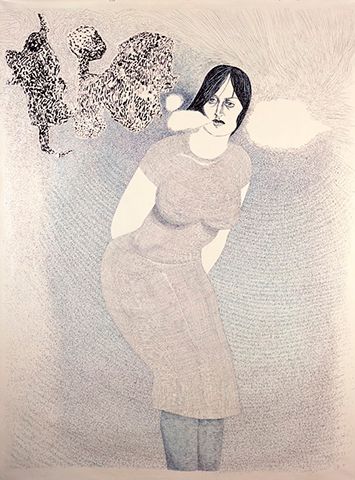

Nadine de Koenigswarter: Fréderic has been following my work for a while. He had already shown the large drawing with dogs which is presented in Vevey as part of an exhibition around the Drawn Notebooks (Le Drawn Book, number 11, April 2016). Frédéric told me about the “Portrait, Self-portrait” project and he chose two of the three Dreams for the exhibition. This series came to a time when I was just doing abstract work on paper and I had a blockage for two, three months. There was a break and I was going around in circles. One evening, I started to draw the first drawing in this series (Songe below) which has its origins in dreams, interior visions, very strong images outside reality, hence the title Songes . I wanted to draw a powerful, well-established woman who takes revenge, but at the same time cannot express herself. It's not me, but it's me in a way. We find in these paintings of women a strength and a fragility and always a protective presence. In the first Dream, there is this benevolent presence at the top left. The second head in Songe from 2010 which is exhibited in Vevey also struck me like that. I don't tend towards surrealism, nothing is ever thought of in advance. I discover the painting when it's done.

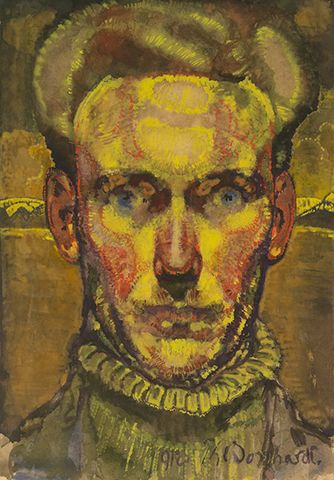

You have chosen "Self - portrait" by Rodolphe-Théophile Bosshard to communicate about the exhibition. Why this choice?

Emmanuelle Neukomm: For Frédéric, it was very important to have Bosshard because it is an emblematic work of the exhibition. It is not necessarily a mad love for the work of the artist, but this piece clashes. She is very contemporary, almost expressionist, with these impossible colors. At the same time, she is in this very tight frame. There is something a little scary about this frontality, it is not very welcoming. He doesn't smile. We are not in a portrait of seduction. The work is all the more astonishing when one knows the somewhat bourgeois and purring painting of Bosshard. At the same time, for us it was important to also have something easier to access for the general public. We also made our choice according to the impact of the image and we said to ourselves that in the street, in large format, that it was going to be impactful. For me, Blanca won. I find her incredibly beautiful. Her profile, her locks, that shadow on the back of her neck. There is something disturbing about her, you can't even see her pupil. At the beginning, we had imagined a very tight framing and finally, we chose a framing a little wider, more traditional. I also liked playing on the idea that the gaze that does not immediately appeal to you because the portrait can be mysterious, it can be from the back - like Confinement of Joël Person - it remains an individuality and it is still a portrait.

Another angle of communication with the Blanca II portrait . Jean-Baptiste Sécheret , can you tell us more about this work?

Jean-Baptiste Sécheret: One day, one of my Colombian students, Felipe, brought one of his compatriots, Blanca. I was shocked when I saw him appear. She was incredibly beautiful, while falling short of thin body standards. She is rather "wide", but sees it very well, she laughs and plays rugby. The girls opposite had better pay attention (laughs). I had never asked a woman to pose for me, just the idea terrifies me. But there, I biased, I said to Felipe: "You have to draw it". Blanca arrived at that moment and I said blushing and with a very small voice "Hello, Felipe has to draw you". A week, two weeks, four months later, Felipe still hadn't drawn it. So I said “that's enough, you come to the workshop with other students and Blanca”. We started to draw her in my studio and since the students were very busy with their lessons, I suggested that Blanca continue without them. She came and I made a sketchbook, including the one on display in Vevey, from the front (Blanca). Afterwards, I took him to the litho workshop. She put on the same dress and I had her pose in the pose of Delacroix's orphan (Young orphan in the cemetery), a very beautiful brunette who looks in the eye almost all white, we only see a crescent moon for the pupil. Blanca will come back to pose, it's planned (smile).

Does the exhibition present particularly offbeat or surprising works?

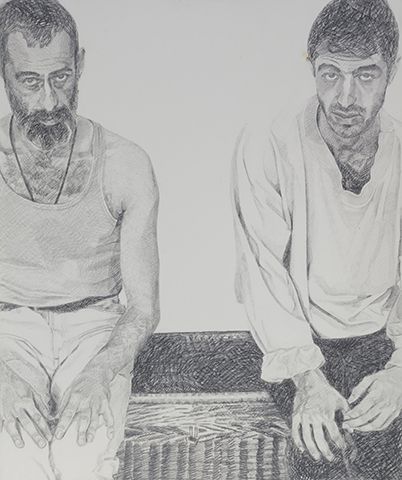

Frédéric Pajak: There is a very small drawing by Cézanne, a small engraving where he really scratched the face against the light (Head of a young girl). I find it very amazing because if you blink, you see someone with glasses that don't exist at all, they're just arcades. It's very daring as a way of engraving, of crossing out the drawing, of trying to erase it with lines. This is what is quite incredible. I find it bold as an engraving. There is also an artist whom we know nothing about, Martial-André Lefebvre. His drawings were in the museum's storage and I found them absolutely amazing. He drew two young boys who are sitting down, a little tucked in (Full-length portrait of Albert Magny, nine and a half years old and Full-length portrait of Bernard Labussière, six and a half years old). There, there is something intimate, powerful, both attractive and repulsive in the portrait of these prostrate children. It's amazing because he's a stranger, he doesn't have a chance to be shown in a museum.

Emmanuelle Neukomm: The portrait of Fayoum was very important for Frédéric because the portraits of Fayoum were identified as the first realistic portraits in the history of art. It dates from the first century, yet it is of a contemporaneity, an individuality and a striking presence. We could meet him when leaving the room. Emilienne Farny is exhibited with her suite of boys (The boys №13 and The boys №16). She made about fifty of them, all in the same formats, quite large and powerful because we find ourselves in the viewfinder of this weapon. She is not an artist that the general public knows.

One of Frédéric's specificities, and one of his qualities, is to marry Kiki Smiths that everyone knows with more confidential artists. The Holy Face of Mellan is also a famous piece which is a technical feat because the artist worked with a single cut which unfolds from the tip of the nose in a continuous line which creates this absolutely surprising face of Christ. The whole difficulty of the chisel game lies in the force, the pressure you exert on the tool. You engrave directly on the copper, you do not have as with etching the varnish which gives you a form of softness and fluidity in the movement. There is also Self - portrait by Mix and Remix (Philippe Becquelin).

It's a job that generates very divergent opinions. There are people who find that great, and others who rebel and say that it is "fuck up." But when he does this self-portrait, he's sick and at the end of his life. There is already an irony, a tension, between this representation and what he experienced. And then there is something so essential. A portrait, that's it. You can draw a face, two dots, a line and a pencil stroke. I think there's a sense of humor in there and then, ultimately, it's fair. It's pim-poum and here we are. But there are plenty of people who will say “my son can do that”. It is clear that it will take your breath away.

Portrait, self-portrait was on at the Musée Jenisch in Vevey From May 29 to September 5, 2021.

To check out the Musee Jenisch please click here.

© A very special thank you to Hannah Starman and the editor of the Swiss art magazine Arteez who have given their permission for the article to be reproduced here on the AnArt4Life blog.

Please follow this link to read more art articles on the ARTEEZ website.

Credit

1. arteez.ch