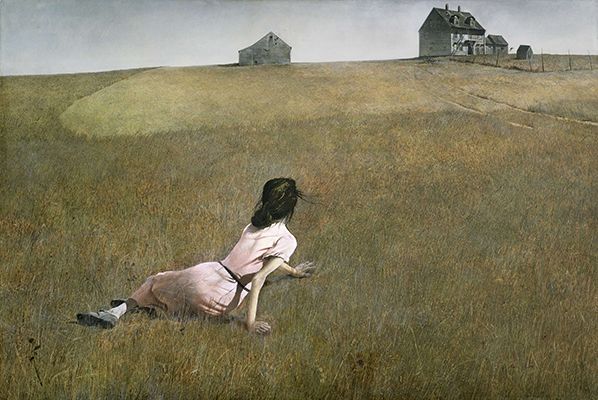

Monday's Feature: Christina's World by Andrew Wyeth

I showed you the painting Christina's World last week when we took a look at some of the paintings of American realist artist Andrew Wyeth. And I promised to tell you the story behind the somewhat unusual image. I have taken this summary from an article Andrew Wyeth, iconic American painter, 91 by Michael Kimmelman published in the New York Times Jan. 16, 2009.

Wyeth had seen Christina Olson, crippled from the waist down, dragging herself across a Maine field, “like a crab on a New England shore,” he recalled. To him she was a model of dignity who refused to use a wheelchair and preferred to live in squalor rather than be beholden to anyone. It was dignity of a particularly dour, hardened, misanthropic sort, to which Wyeth throughout his career seemed to gravitate. Olson is shown in the picture from the back. She was 55 at the time. (She died 20 years later, having become a frequent subject in his art; her death made the national news thanks to Wyeth’s popularity.)

It is impossible to tell her age in the painting or what she looks like, the ambiguity adding to the overall mystery. So does the house, which Wyeth called a dry-bone skeleton of a building, a symbol during the Depression of the American pastoral dream in a minor key, the house’s whitewash of paint long gone, its shingles warped, the place isolated against a blank sky. As popular paintings go, “Christina’s World” is remarkable for being so dark and humorless, yet the public seemed to focus less on its gothic and morose quality and more on the way Wyeth painted each blade of grass, a mechanical and unremarkable kind of realism that was distinctive if only for going against the rising tide of abstraction in America in the late 1940’s.

“Oftentimes people will like a picture I paint because it’s maybe the sun hitting on the side of a window and they can enjoy it purely for itself,” Wyeth once said. “It reminds them of some afternoon. But for me, behind that picture could be a night of moonlight when I’ve been in some house in Maine, a night of some terrible tension, or I had this strange mood. Maybe it was Halloween. It’s all there, hiding behind the realistic side.”

He also said: “I think the great weakness in most of my work is subject matter. There’s too much of it.”2

If you would like to read more about the painting Christina's World follow the Bookmark link below.

Footnotes

- atlasofplaces.com

- nytimes.com