Ivan Morozov and Sergei Shchukin: Collectors of the Parisian Avant-garde by Hannah Starman Nov 2021

The following article was written by Hannah Starman and published in the Swiss arts magazine Arteez. It is reproduced here with permission.©

The article features an interview conducted by Hannah Starman with art historian Natalia Semenova.

Natalia Semenova is an art historian, biographer of Sergei Shchukin and the Morozov brothers, and co-author (with director Tania Rakhmanova) of two documentaries on the Russian collectors of the French avant-garde. She talked to us from New York, where she is currently researching her next project. Her friend Tanya Chebotarev, curator of the Bakhmeteff Archive at Columbia University, contributed to our discussion on the lives and times of the merchants who amassed the most extraordinary collections of modern Western art in the world. The Morozov collection: Icons of Modern Art is displayed at the Louis Vuitton Foundation in Paris until 25 July 2022.

Hannah Starman for Arteez: You have devoted your entire professional career to the lives of Russian private art collectors and have authored the definitive biographies of Sergei Shchukin (The Collector: The Story of Sergei Shchukin and His Lost Masterpieces) and the Morozov brothers (Morozov: The Story of a Family and a Lost Collection). What sparked your interest in the subject?

Natalia Semenova (NS): I studied art history at Moscow University in the early 1970s and worked at the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts at the same time. There, I met Alexandra Andreevna Demskaja, an elderly archivist who devoted her life to researching the Muscovite art collectors. I was young, spoke English, and learned French, so I helped her with her research. The names of those art collectors were totally unknown at that time. There was no private property in Soviet Russia after the revolution, so we naturally assumed that all the artworks in our museums came from the government. I wanted to write my Master's thesis on Sergei Shchukin and the Stein family (Leo and Gertrude), but the legendary director of the Pushkin Museum, Irina Antonova, who headed the museum for over fifty years, said: “No, this is not for us. ”It wasn't until the perestroika in 1989 that one could publish long forbidden authors such as Marina Tsvetaeva and Boris Pasternak, and write about Russian private collectors. I wrote the first article on Morozov and Shchukin in 1989 in The Light, a trendy magazine that sold millions of copies. In 1993, I co-authored two publications: a small but informative book entitled "With Shchukin on Znamenka" with Alexandra Andreevna and "Collecting Matisse" with Albert Kostenevich, the chief curator of the Hermitage Museum. Collecting Matisse was particularly significant because it established the relationships between Russian collectors and Henri Matisse for the first time.

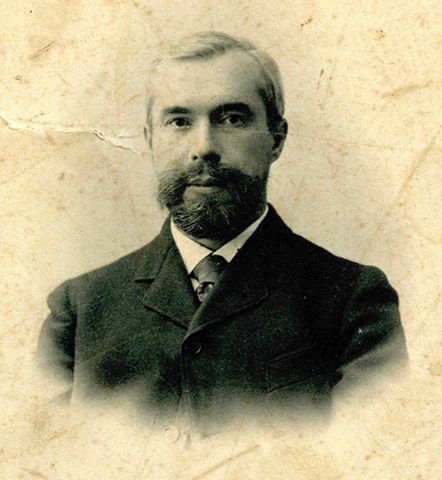

Hannah: Sergei Shchukin and the Morozov brothers, Mikhail and Ivan, were the most important collectors of modern French art in Russia. What can you tell us about them?

NS: The merchant collectors of Western modern art were the oligarchs of their time, and they established their businesses and built their collections in booming, industrialized and Europeanized Moscow. Both the Shchukins and the Morozovs were merchants, and their wealth came from textile. Ivan Morozov was a graduate of the Federal Polytechnic School in Zurich (ETH Zurich). By 1913, his textile mill employed 13,000 people, and he was considered one of the richest men in Russia. Like many industrial entrepreneurs, the Shchukins and the Morozovs were Old Believers and relatively new money. For example, Morozov's great-grandfather was a serf who bought his freedom with his wife's dowry of five rubles. Old Believers were Eastern Orthodox Christians who maintained the liturgical and ritual practices dating back to the 17th century, before the reforms caused the schism. Like Jews and other minorities, they were persecuted, banned from big cities, forbidden to join civil service, subject to special taxation, etc. Many fled Russia or converted.

Tanya Chebotarev: The rivalry between entrepreneurial Moscow and aristocratic Saint Petersburg manifested itself in art collecting. The Tsar's family and the nobility, the Russian aristocrats, collected the “classical” artists: the Dutch masters, the Germans, and the like. As Old Believers, living in Moscow and coming from nowhere, the capitalist businessmen rejected the old-world aristocrats and everything they stood for. They wanted to be different, yet in a way, they imitated them. Old Believers started their collections with traditional art but quickly moved on to explore other artists and different approaches to art. They had the money and - fortunately for us - excellent taste too.

Hannah: What was their approach to collecting? Was there any rivalry between the collectors?

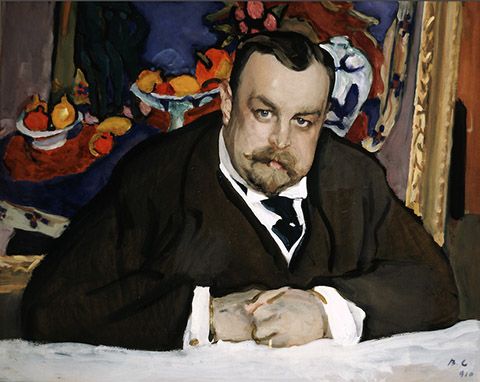

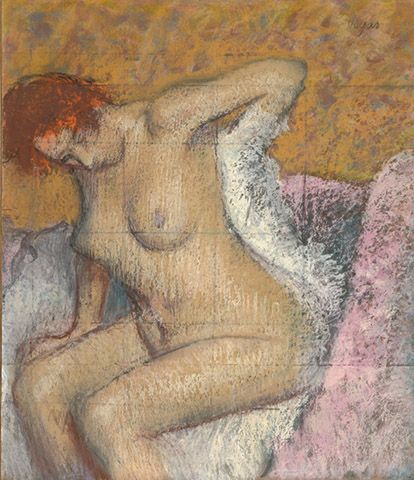

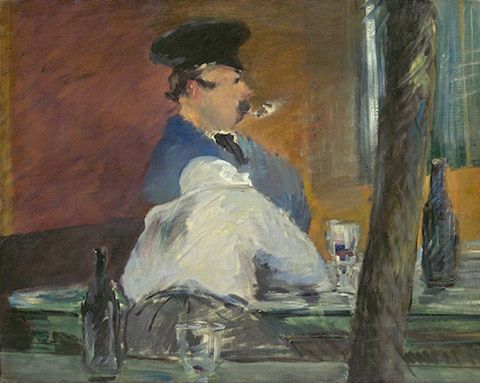

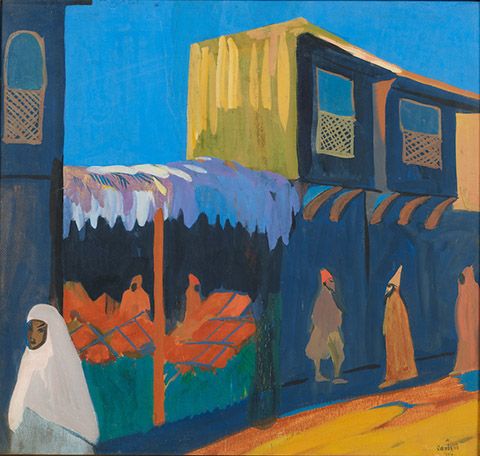

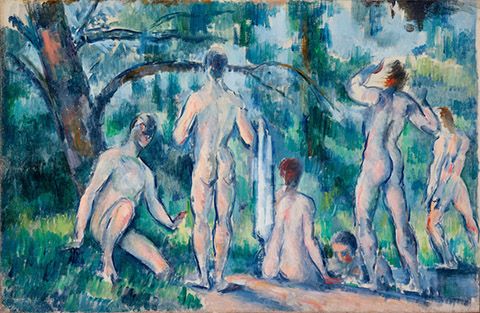

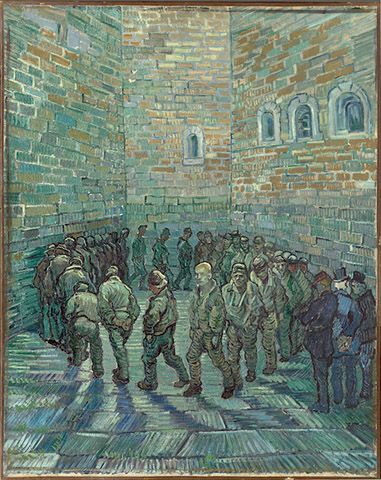

NS: No, never. The art market was so huge at the time that there was no need for it. I analyzed the pieces that Shchukin bought and those that Morozov chose, and the two had completely different tastes. Sergei Shchukin, who was 17 years older than Ivan Morozov, started collecting much earlier and his collection of 257 pieces was radically modern. He defended Picasso and cubism, whereas Morozov preferred the Nabis. Mikhail Morozov, the elder of the Morozov brothers, died at 33, and when his brother Ivan took over the collection in 1903, it consisted of 39 French and 44 Russian works. Unlike Shchukin, who was interested exclusively in foreign artists - he had 51 Picassos, 37 Matisses, 13 Monets, 8 Cézannes, 16 Gauguins, etc. - Ivan Morozov amassed an impressive selection of Russian avant-garde as well. When the Morozov collection was nationalized in 1918, it consisted of 188 foreign and over 300 Russian paintings. Ivan Morozov was also the first Russian collector to purchase works of Marc Chagall in 1915. It was the modest income from this sale that allowed Chagall to return to Vitebsk and marry Bella.

NS: They also had a different approach to collecting: Sergei Shchukin would go head over heels about an artist, purchase all his paintings - which he selected himself - and move on when he discovered someone else. He was in love with Monet and Renoir for four years; then, he fell in love with Matisse, etc. If he had bought a Renoir in 1903, he would never buy a Renoir in 1913. His collection is a history of his passions. On the other hand, Ivan Morozov could purchase works by the same painter throughout his life because he was building a museum. His acquisitions this strategy: relying on trusted advisors, Morozov bought pieces representing all the different trends, thematically close, and harmonious in terms of color.

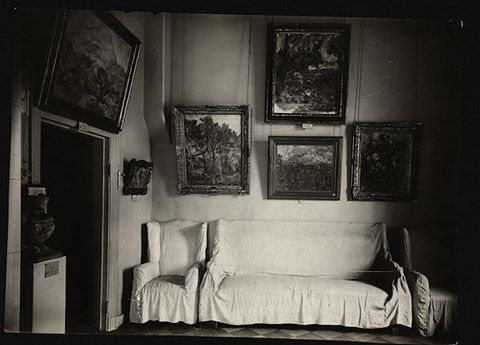

NS: The two patrons of the arts exhibited their collections in their respective palaces, but while the Shchukin collection was open to the public every Sunday free of charge from 1908 onwards, Morozov would only grant access to prominent foreign visitors upon special request.

Hannah: The Soviet government nationalized the collections after the October Revolution. What happened to the artworks between 1918 and 1989?

NS: At the time of the October revolution, the Shchukin collection represented practically the whole progress of modern French painting from the 1870s to Picasso's cubism. The collection initially remained at his Trubetskoy Palace and became the first Museum of Modern Western Painting. When it opened in 1919, it was the first state-funded modern art museum in the world, before the Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art in New York. The Second Museum of Modern Western Painting was established at the Morozov mansion on Prechistenka street. The two museums and the two collections were united in 1928 when the State Museum of Modern Western Art was established and housed at the former Morozov palace.

NS: Nothing was ever stolen or destroyed, but there was the practice in the Soviet Union in the 1930s to send paintings from the capital to provincial cities. After the collapse of the Soviet Union a few pieces from the Morozov collection thus found themselves outside of Russia: in Georgia, Ukraine and Azerbaijan. Most are painted by minor artists, but there is also a beautiful portrait of Margarita Morozova by Valentin Serov in the exhibition, and the painting comes from Dnipropetrovsk in Ukraine. In 1933, as part of the covert operation to raise foreign currency, the Soviet government sold two pieces from the Morozov collection: Van Gogh's “Night Café” and Cezanne's “Madame Cezanne dans l'Orangerie.” During the Second World War, the artworks were moved to Novosibirsk.

Hannah: The western public first learned about the existence of these stunning collections of modern French paintings in the Soviet museums in the 1980s through a book written by a wealthy socialite and art collector, Beverly Whitney Kean.

NS: Yes, this is a fantastic story. Beverly Whitney Kean came to Russia in 1959 as one of the first tourists allowed to travel to the Soviet Union. She visited the Pushkin Museum in Moscow and the Hermitage in Leningrad and was shocked to see these masterpieces of French modern art there. Nobody seemed to know who had bought them. Beverly spent the next twenty years researching Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, whose names had been wiped from the Soviet art history after the revolution. She was wealthy and could afford to travel and hire interpreters to conduct her interviews. I was surprised to learn how much she was able to achieve, given that she was not an art historian and could speak neither French nor Russian, but she talked to Matisse's children and even flew to Beirut to meet with Shchukin's son Ivan when he was still alive. Her book All the Empty Palaces: The Merchant Patrons of Modern Art in pre-Revolutionary Russia was published in London in 1983. It was a bombshell: it revealed the existence of these treasures to the West, but even more so their "capitalist" origin to the Russians. We discovered this book by pure coincidence after someone had smuggled it to Moscow in the late 1980s. It was banned in the Soviet Union until the fall of the communist regime. My friend Hilary Spurling (Henri Matisse's biographer) and I visited Beverly at her castle in the north of England in 1991. She was a marvelous person.

Hannah: How and when were these masterpieces first introduced to the Western and Russian audiences?

NS: The first exhibition of the Shchukin and Morozov collections was organized at the Folkwang Museum in Essen in 1993 to mark the 30 th anniversary of the German firm Ruhrgas, a major importer of Russian gas into Western Europe. I helped them with the catalog, Beverly Whitney Kean came to the opening, and the exhibition was a huge success (it attracted 600,000 visitors). In 1994, the exhibition Morozov and Shchukin, Russian Collectors. From Monet to Picassowas shown at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow and at the Hermitage in Saint Petersburg. The show included a reconstruction of the Music Room in Ivan Morozov's palace, with its thirteen paintings of the “Story of Psyche” by Maurice Denis. The Music Room has also been reconstructed at the current exhibition at the Louis Vuitton Foundation. However, unlike the Morozov show in Paris, the 1993 German exhibition also included Van Gogh's “Night Café” from the Yale University Art Gallery and the portrait of Madame Cézanne from the Metropolitan Museum of Art, sold in the famous Stalin sales in 1933. I wrote about this in my book Selling Russia's Treasure: The Soviet Trade in Nationalized Art, 1917-1938.

Hannah: In collaboration with Sergei Shchukin's grandson, André-Marc Delocque-Fourcaud, you wrote the project for the Icons of Modern Art. The Shchukin Collection, the exhibition that drew the record-breaking 1.2 million visitors to the Louis Vuitton Foundation in 2016-2017. How did you make it happen?

NS: We wrote the proposal in 2014 and showed it to the director of the State Hermitage, Mikhail Piotrovsky. He confirmed that the Hermitage had all the pieces needed for the Shchukin exhibition and would loan them. We started looking for a museum that could organize such a large and expensive exhibition. The costs of insurance and transport alone were prohibitive for most institutions. We could not find a public museum, but the Louis Vuitton Foundation had just opened, and André-Marc knew Jean-Paul Claverie, the advisor to Bernard Arnault (CEO of LVHM). Claverie submitted our proposal to Bernard Arnault, and his reply came 24 hours later: “I want it.” We understood that the French exhibition would require a biography of the unknown Russian collector. We wrote the biography of Sergei Shchukin in French, and Yale University Press later published it in English. At the same time, Tania Rakhmanova and I made the documentary on Shchukin for ARTE (Sergey Shchukin, the novel of a collector). I also compiled the catalog for The Shchukin Saga exhibition at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow in 2019 with Matisse's masterpiece “The Dance,” an exceptional loan from the Hermitage. As an expert consultant, hired by the Louis Vuitton Foundation for the exhibition, I happily shared my scholarship of almost forty years with the chief curator, Anne Baldassari, who compiled the catalog Icons of Modern Art: The Shchukin Collection.

Hannah: The current exhibition of the Morozov collection at the Louis Vuitton Foundation promises to be an even bigger blockbuster than the Shchukin show in 2016. How were you involved in this project?

NS: About twenty years ago, Ivan Morozov's great-grandson Pierre Konowaloff and his then-wife invited me to visit them in Paris. They had read my book about the life and the collection of Sergei Shchukin and asked me to write about Pierre's great-grandfather.

I was reluctant at first, but then Pierre Konowaloff showed me three items: his grandmother's passport, a photograph of the family dacha, and a photograph of Ivan Morozov taken a few weeks before he died. His eyes and face looked as if all life had already left them, like a death mask. I cried when I saw this picture, and I committed to writing the book.

NS: But how was I to write the story of someone whose only legacy were a sun-bleached photograph, two portraits and a single interview? All we had were Maurice Denis' diaries and a few letters between Ivan Morozov and his artists. Sometimes my work as an art historian reminds me of detective investigation. I finished my first Morozov's biography ten years ago, but I have never stopped working on the next one, collecting an ever-growing number of unknown facts and documents and hoping that one day my research would be published in English. I was especially gratified when, having read my manuscript in Russian, Yale University Press editors immediately offered to translate it and publish it in English. In the meantime, the book has also appeared in French and Italian. We made a documentary on Morozov with Tania Rakhmanova (La Dynastie Morozov ou l'art à la folie , 2020), and I have recently completed the catalog for the Morozov exhibition that will open in Moscow on 31 May 2022.

Anne Baldessari also curated the Morozov exhibition, but my expertise was not needed this time. My involvement was limited to writing two articles: Ivan Morozov. The Quest for Harmony, published in the exhibition catalog, and Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov. Passion and Harmony that appeared in the Le Journal of the Louis Vuitton Foundation.

Hannah: As the author of several catalogs, biographies, films, etc. on the Shchukin and the Morozov collections, you are perfectly familiar with all the pieces that compose them. Were all the paintings shown in Paris part of the original collections?

NS: No, definitely not. But we cannot question the curatorial concept of the exhibition. The chief curator, Anne Baldessari, intended to show the panoramic view of the Russian art scene of the time. This is why only 23 out of 40 Russian paintings shown were from the Morozov collection. For example, several Russian paintings in the portrait room have never belonged to the Morozovs. On the other hand, all foreign artworks came from the Mikhail and Ivan Morozov collections. A similar curatorial choice was made at the Shchukin exhibition, where Kasimir Malevich's Four Squares followed the Shchukin's Picassos although Sergei Shchukin had never bought a single Russian painting.

Hannah: All the “turn of the century” Russian collectors of avant-garde art were oligarchs. Are contemporary Russian oligarchs also interested in art?

NS: Of course. I know it because I prepare catalogs for very important Russian collectors of modern art. Some of them are well educated and spend vast amounts of money on art. It's an essential part of their lives. Shchukin and Morozov are their heroes; they look up to them.

The Morozov collection: Icons of Modern Art

Louis Vuitton Foundation, Paris

Until 25 July 2022

www.fondationlouisvuitton.fr

© A very special thank you to Hannah Starman and the editor of the Swiss art magazine Arteez who have given their permission for the article to be reproduced here on the AnArt4Life blog. It is a rare opportunity to be able to share such indepth insights as expressed by Natalia Semenova.

Please follow this link to read more art articles on the ARTEEZ website.

Late Mail

A very warm welcome to C.L. in Louisiana, USA who has joined the AnArt4Life blog community.

Whether you live in the southern hemisphere where it is about to get too hot to go outside in the middle of the day or in the northern hemisphere where the winter cold will keep you inside - there will be a daily post from the AnArt4Life team for you to read.

Credit

1. https://arteez.ch/