The Staffordshire Potteries

In a recent post on Willow ware (click here) we discovered that the mass production of this popular blue and white china is accredited to Josiah Spode, one of the many potteries that abounded in the Stoke on Trent area of England in the 18th and 19th centuries.

This got me thinking about other potteries of the area. In the boom times there were over 200 potteries producing a vast variety of wares!

I don’t propose to bore you by covering every single one of them, but I thought it might be interesting to visit a few of some of the more well-known names. You, or your mother or grandmother, may have had a few pieces! You may be familiar with names such as Wedgwood, Royal Doulton, Spode, Aynesley, Coalport or Moorcroft, which were exported worldwide in the 19th and 20th centuries. Some still continue production in the same area to this day.

The English potteries that we will look at in coming posts are known collectively as The Staffordshire Potteries, or just “The Potteries", as they are centred in the Staffordshire area of England, and more particularly in the area called Stoke-on-Trent since 1910.1

However, Stoke on Trent is actually a collective term for six separate towns, Burslem, Fenton, Hanley (the city centre), Longton, Stoke and Tunstall. This area became the popular centre of potteries as it had the right sort of clay available, plenty of fresh water from the River Trent, a ready workforce and a train network nearby for distributing its production.

British pottery covers everything from functional cups, saucers and jugs to ceramic tiles, ornaments and vases, sewerage pipes and bathroom ware!

But before we get into specific brands, a little bit of history and some explanation of terms might be useful…….

-

Firstly, Pottery and ceramics mean the same thing and are interchangeable terms, meaning objects made with clay, hardened by firing and then decorated or glazed.

-

Fragments of the world's oldest pottery were found in southern China, dating back some 20,000 years. It is thought that the potter's wheel was invented in Mesopotamia sometime between 6,000 and 4,000 BC and it revolutionised pottery production. Moulds were used to some extent as early as the 5th and 6th century BC by the Etruscans and the Romans. The first high-fired glazed ceramics were produced in China, during the Shang dynasty period (1700-1027 BC).

- There are three broad categories of pottery – earthenware, stoneware and porcelain. Broadly, they differ in their clay components and the temperature they are fired at.

A. Earthenware is the earliest form of pottery, occurring throughout the ancient world from Neolithic times, predominantly using red or brown clay to make cups, plates and jugs etc. Earthenware is slightly porous after its first firing in a hot kiln. It is made waterproof by the application of slip, a liquid clay mixture applied before the second firing, or by the application of a tin or clear glaze.2

There are two main types of glazed earthenware:

One is a transparent lead glaze. When the earthenware body to which this glaze is applied has a cream colour, the product is called creamware. 2

The second type is an opaque white tin glaze, is variously called tin-enamelled, or tin-glazed, earthenware, majolica, faience, or delft (not to be confused with Dutch Delftware). This tin glaze became popular from the 16th century onwards, when craftsmen from Germany and Holland brought this technique with them to the UK when they migrated due to religious persecution.

B. Next we have Stoneware, which is pottery that has been fired at a higher temperature than earthenware. The higher temperature of approximately 1000 degrees C is high enough to partially vitrify the materials and make it impervious to liquids even when it is unglazed. Vitrification is the formation of glass using heat. In pottery, it is usually achieved by heating the clay until it liquidises, then cooling the liquid, often rapidly, so that it passes through the glass transition to form a glassy, but impervious solid. So it doesn’t need to be glazed!

John Dwight, an alchemist and venture capitalist from London, was the first to solve the mystery of how to produce stoneware. In 1672 he opened his factory, Fulham Pottery, which remained in business for 300 years. The factory no longer exists but the bottle kiln still does.

C. The third category of pottery is Porcelain, of which there are three types – hard paste porcelain, soft paste porcelain and bone china. These differ in the additives to the clay.

Hard-paste porcelain is made from a mixture of china clay (kaolin) and china stone (petuntse).

Soft paste porcelain is made with white clay and a mixture of white sand, gypsum, soda, salt, alum and nitre. Lime and chalk were used to fuse the white clay and the frit, the mixture is then fired at a lower temperature than hard-paste porcelain.

Bone china is created by adding animal bone ash to the ingredients for hard-paste porcelain, which gives it a translucent, ivory white appearance. It is stronger than hard-paste porcelain and easier to manufacture. This explains why it can be quite delicate, so you can see your hand through it, but is still quite strong and a beautiful snow white colour, such as these images of Royal Albert and Wedgwood tea sets.

- The word china was used in 17th-century Britain to describe porcelain imported from China and used to distinguish it from homemade earthenwares. At that time Europeans were unable to manufacture porcelain, which was an expensive and highly prized material.

In 18th century Britain, a fashion for tea-drinking generated a big demand for porcelain from China, specifically the Jingdezhen region4 and collecting ‘china’ became a competitive passion. As a result, concerted efforts were made to discover the secrets of its manufacture. The true development of bone china is attributed to Josiah Spode in 1794 and production began in his factory around 1800.2,3

- Transfer printing onto china also became popular at this time enabling wares (such as Willow ware) to be mass-produced and not subjected to the labour intensive process of hand-painting.4

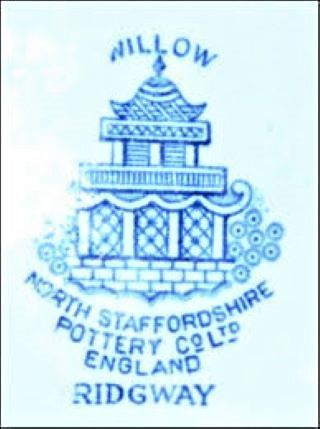

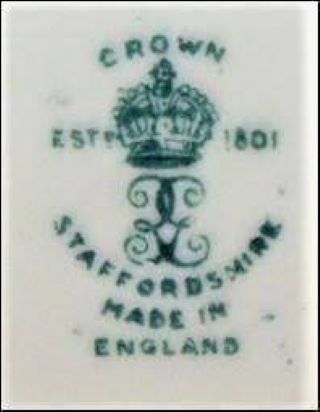

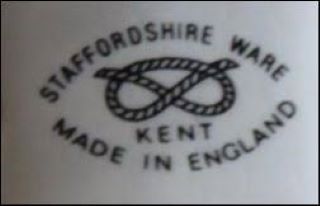

- Some pottery pieces have “Made in England”, or the specific town, eg. “Burslem”, or later, just “England” stamped on their bases as well as other unique marks to identify the specific pottery maker.

These agreed backstamping conventions are a way of broadly dating particular pieces.

Now that your head is spinning from all these terms related to the production of English pottery, we will take a break, and return very soon to look at one of the earliest and most well-known names of the Staffordshire area, Wedgwood.

If you would like to learn more about the various terms that apply to ceramics and pottery, please click here for 'The A-Z of Ceramics'.

And a very warm welcome to C.C. in the Philippines who has joined the Anart4Life blog as our latest subscriber.

Footnotes

- With thanks to Wikipedia

- With thanks to thepotteries.org

- With thanks to the Victoria and Albert Museum, vam.ac.uk

- With thanks to comestepbackintime.wordpress.com