Long Lost Australian Artists: Clarrie Cox - A Bonza Bloke: Part 1

Before we get onto today's post, we have to welcome two more subscribers in P in Melbourne and S.L. in Balwyn who have joined us. What a wonderful week we have had and I think we must thank our Caroline for encouraging the Marvellous Movie Girls to join up. We loved being At Home with the MMGs last week and look forward to learning more about their art interests.

But today we are not At Home but On the Road.

Guest Writer: John Wylie from Port Elliot, South Australia has co-produced this post on Clarrie Cox.

We would never have learnt about the works of Australian artist Clarrie Cox if subscriber and fellow artist John Wylie from Port Elliot in South Australia hadn't gone to a market some weeks back. Browsing through some books John came across a publication which showcases the paintings of Clarrie Cox.

Clarrie Norman Cox (1927-2013) studied at the East Sydney Technical College and worked as an advertising display artist, operating his own business until 1973, when in his 40s he took up oil painting and began painting the historical buildings from the early days of European settlement in Australia.

Please come on the wallaby track1 with Clarrie Cox, John Wylie and me and enjoy Clarrie's record of buildings from all the states and territories in Australia.

We have included with each painting the description that accompanies it in the book as it gives a fascinating insight into the location and subject matter that Clarrie decided to paint.

When Clarrie Cox created his paintings he envisioned taking the viewer back in time where the backdrop of the land and the wide sky reminds us of our flimsy tenure of a vast and ancient land.2

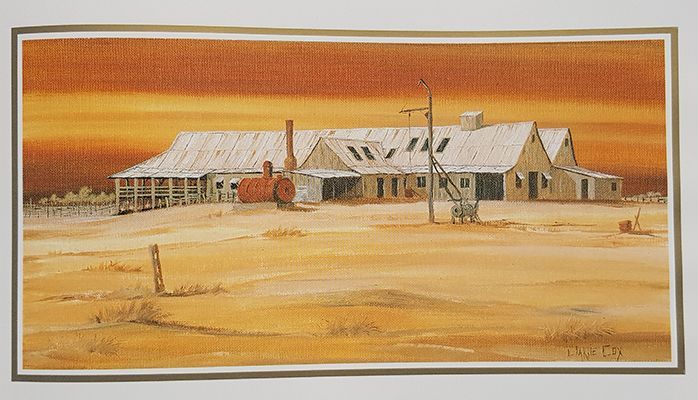

As Clarrie came from Sydney we are going to visit New South Wales first and where better to start than with two of John Wylie's favourite Clarrie Cox paintings which emphasise the importance of humble buildings such as a shearing shed (as seen below) against the huge expanse of the Australian sky.

When the explorers Burke and Wills passed through the area west of the Darling River in 1860, Kinchega station had already been taken up. The vast country with its big skies demanded men with expansive ideas and aspirations: by 1876 Kinchega boasted a huge 26-stand shearing shed and accommodation for forty shearers; by 1889 the property supported 143 000 sheep, and there was an adjoining cattle station. Today the shearing shed is the only reminder that Kinchega was once one of Australia's finest stations in far-west New South Wales. Kangaroos have roamed the salt-bush studded plains in place of sheep since 1967 when the station became a national park. Now covering over 44 000 hectares, the park incorporates the sleepy, steep-banked Darling River which river boats once plied, providing a vital link between far-flung stations and civilisation. Majestic river gums line the banks of the Darling, while the outlying red sandhills and plains carry the hardy plants of the desert; after rain the sandy reaches are transformed into a carpet of yellow, green and purple. Overflow lakes store excess water from the river, ensuring the mining town of Broken Hill to the north a constant water sypply. An oasis in a barren country, these lakes offer shelter and feed to a wide range of waterbirds whose eerie calls ring out across the cold night skies. Lunettes have been formed over the centuries on the eastern shores of the lakes and have proved to be rich in archaeological sites, the oldest dating back 26 000 years. While the relic of the woolshed serves as a reminder of the struggles of early European pioneers, the bones and implements found in Kinchega National Park are significant for the understanding of Australian pre-history. 2

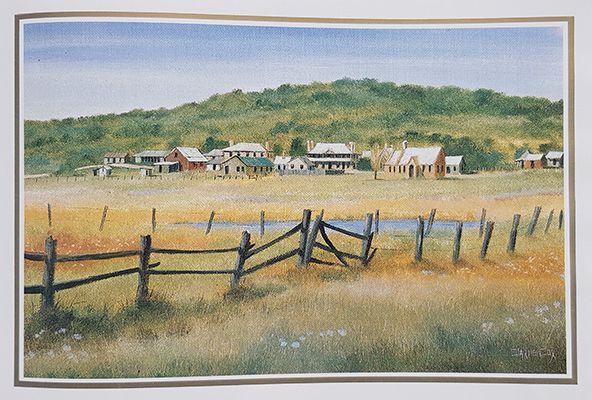

John also likes Wollombi in NSW (below) a tribute in a way to the significance of the endless staggering fence posts that those of us with a rural background know so well. I'm rather fond of painting a fence post myself. I also like this painting as it shows a softer Australian landscape and the nest of buildings which go to make up a country town: a church, a pub, a more substantial home surrounded by the humble abodes of the workers.

It is difficult to believe that the Napoleonic Wars played a part in the settlement of Australia. In fact, the small community of Wollombi inland from Newcastle was founded in the 1830s when soldiers were each granted 40 hectares on their discharge from the New South Wales regiment. Today their graves pay tribute to the pioneering days when the township was a major stop-over on the route between the Hunter and Hawkesbury rivers, a role which ended with the introduction of shipping to the Hunter and with the construction of better roads which bypassed the settlement. Tucked away in a green corner of the Hunter Valley, the historic stone buildings of Wollombi, some of which date back to the early days of settlement, recall the pioneers whose war efforts established the township. 2

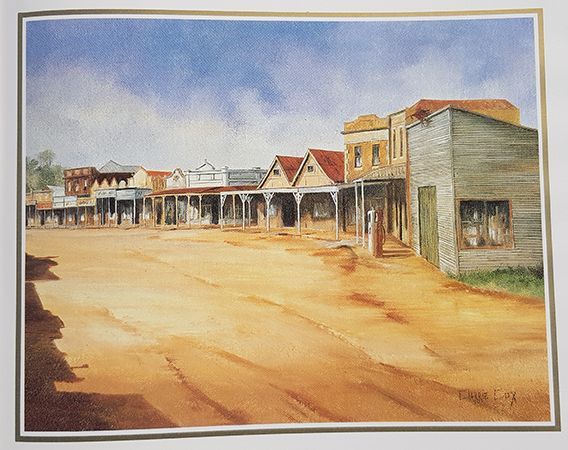

One of my favourite paintings is of Clunes in Victoria (below), a town I know well. To this day this Victorian goldrush town remains very similar to the image as created by Clarrie but it does have a bitumen road. Many of Clarrie Cox's paintings feature the wide expense of dirt that is iconic to the Australian country town.

The sleepy nature of this street-straggle of shopfronts belies the fact that the small township of Clunes north-west of Ballarat was the site of Victoria's first gold-rush. The population in Melbourne had been depleted so severely by the exodus to the New South Wales gold-fields early in 1851 that a Gold Discovery Committee offered a reward to anyone who could find a payable field within 320 kilometres of the settlement. The rush to find gold in Victoria was on. Although William Campbell discovered gold on Donald Cameron's Clunes property in March 1850, the news of the find was kept a close secret. It wan't until late in June 1851 that James 'Civil Jim' Esmond struck Victoria's frist payable gold also near Clunes. Two years later, Esmond received a reward of ₤1000, a somewhat niggardly amount when one considers that by the 1870s over 13000 people were working the Clunes field and spending their fortunes in the thirty-seven hotels in the township. The buildings which this newly-found wealth afforded sprang up along a creek flat and remain today much as they did when horses carried hopeful miners into town. Humble vernacular shopfronts sporting verandas confront the street with as much dignity as the prestigious two-storeyed banks which answered the call of gold. Set in a deep valley surrounded by twenty-two extinct volcanoes, Clunes takes on a whimsical air in autumn when oaks and elms burn bright in a silent testimony to the men and women who attempted to create a little permanency amidst the chaos of the gold-fields.2

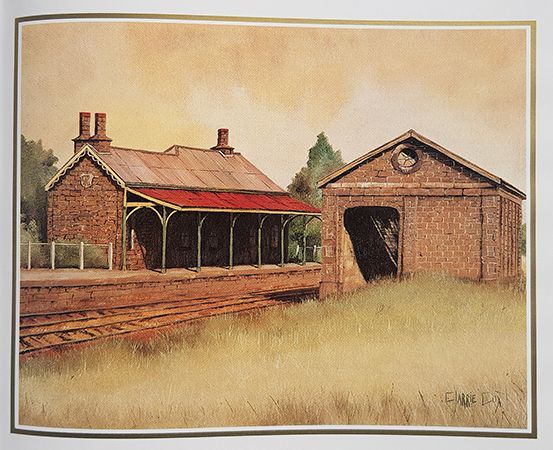

And there was no future for any of these frontier country towns without the railway station as shown below in another of my favourite Clarrie Cox paintings.

Western Victoria is noted for its bluestone buildings and this railway station at the small settlement of Little River, near Geelong, shows how seriously and solidly the architects and builders of the 19th century took their work. The building, with its station master's residence and, across the tracks, train stable and goods shed, makes a handsome picture which reflects the classical stylistic values of the mid-Victorian age, and the civilising strength of the railway as it linked the communities in the wide pastoral lands of the still young colony. They were built in 1864 when the gold-fields had yielded their easy riches and the colony was settling down to pursuing the more prosaic virtues of agrarian wealth and steady progress. The rich, volcanic soil in the plains around Little River were ideal for the purpose, and the goods shed was surely host to a fortune in wool for the Melbourne markets and the spinning wheels of Manchester and Bradford at a time when England was the centre of industrial wealth and progress.

We must point out at this point that Clarrie Cox liked to apply a "golden glow" to his paintings; no doubt because the rich red earth that makes up much of the countryside, the climatic conditions and the dominance of the Sun creates a golden blanket that covers the landscape.

The station at Little River is in fact made of bluestone but in Clarrie's painting appears "red" as he often envelopes the buildings in a golden blanket.

John Wylie and I are going to publish a second post on the paintings of Clarrie Cox very soon. However to conclude today's post we want to showcase the great Australian pub - every country town had one, two...twenty, thirty or more pubs when in their heyday. The township of Clunes (above) had thirty-seven pubs at the height of it life.

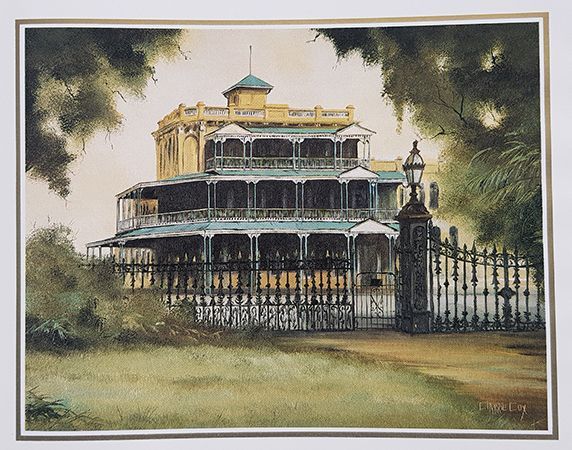

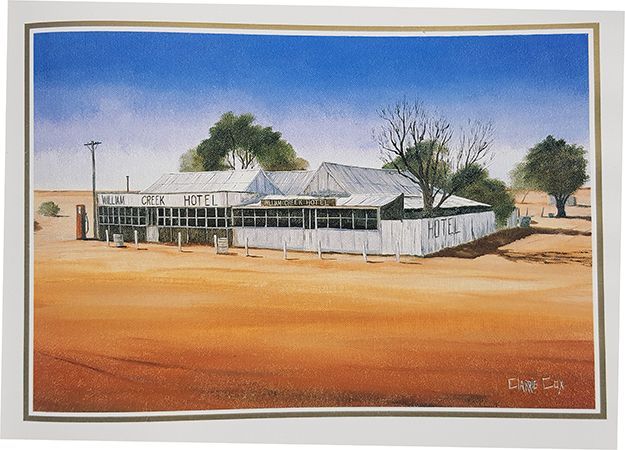

Clarrie Cox painted many Australian hotels: some grand and imposing like the Botanic Hotel Adelaide in South Australia. Others, little more than a large shed as in the William Creek Hotel again in South Australia. No matter the size - inside the pub to this day - the Australian spirit of community is alive and well.

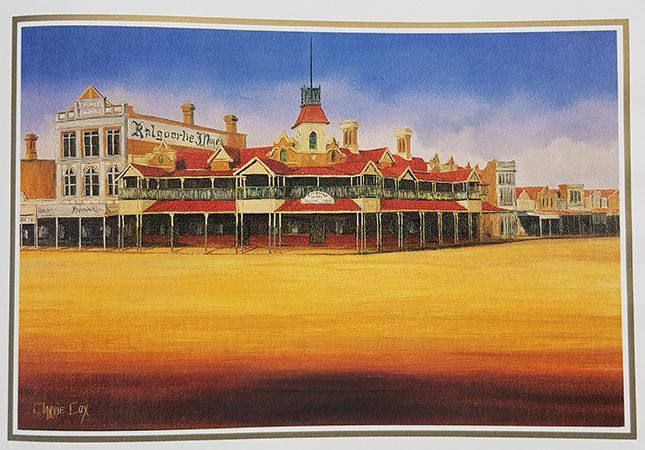

John's favourite Clarrie Cox painting of a hotel is The Exchange Hotel in Kalgoorlie, Western Australia. As John says it's a masterpiece with all the angles and verandahs and again the wide street expanse of red earth and dust.

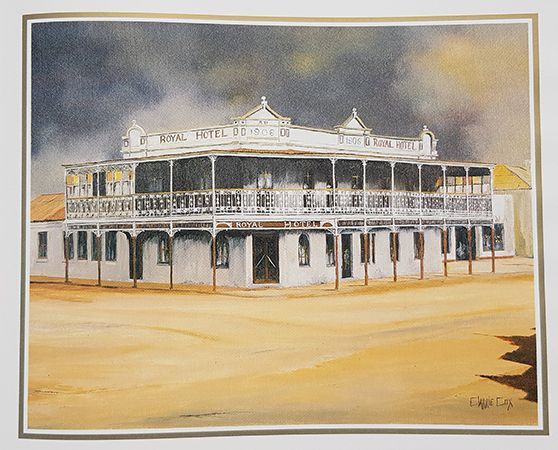

I love the Royal Hotel in Jeriderie, New South Wales. So typical of a country hotel with its wide verandah and cast iron lace work. As a child I travelled all over the east coast of Australia with my parents and stayed at many a hotel that looked just like this. Lovely memories tucked away in the back of my mind.

And for something very grand we have the Botanic Hotel in Adelaide, south Australia which is very suited to being located in Australia's most elegant city.

We want to conclude our exhibition with the William Creek Hotel also in South Australia. This is very typical of the outback pubs. Waiting inside - a cold schooner of beer to refresh the hot and tired traveller. And note a petrol bowser to fill up your fuel tank before setting off once more into the distance.

Additional Note:

Since writing this post we have learnt from Clarrie's daughter that a friend of Clarrie's owned the William Creek Hotel and asked him to paint its image. Clarrie drove from Sydney (NSW) to William Creek near Kati Thanda–Lake Eyre in South Australia to take the necessary photographs - returning home to paint the image as shown below.

Clarrie Cox's ruins and his humble houses and shops, his country streetscapes and wide landscapes are undoubtedly picturesque but they also bring us back in touch with our pioneering times and the will of a strong people who sought to establish their place in a new land.

Clarrie Cox had more than ten one-man exhibitions and his work is represented in private collections around the world.2

Our research has revealed that Clarrie Cox also painted wildlife, especially birds.

If anyone knows more about Clarrie Cox, the artist, and his works please get in contact with me.

Footnotes

- An Australian colloquialism used to describe wandering the outback like a swagman from place to place looking for work.

- Clarrie Cox Australia published by Currey O'Neil, South Yarra, Victoria, 1985. This book was produced as a follow up to Clarrie Cox Historic Towns of Australia, published by Currey O'Neil Ross, 1984.