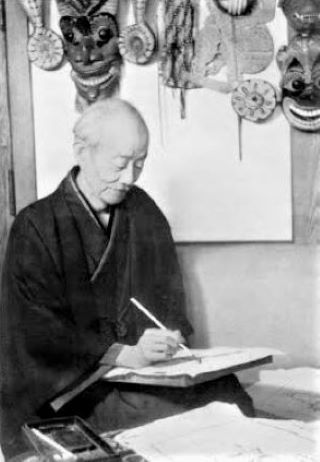

Hiroshi Yoshida - painter, printmaker and pioneer - Part 1

Following on from our recent introduction to the History Japanese Art Part 2 click here, we are going to look at one of the artists from the Taisho Period in a little more detail.

Hiroshi Yoshida was a 20th-century Japanese painter and woodblock printmaker. He is considered one of the leading figures of the revival of Japanese printmaking after the end of the Meiji period in 1912, and into the modern era, but was also influenced by the Impressionists and other Western techniques.

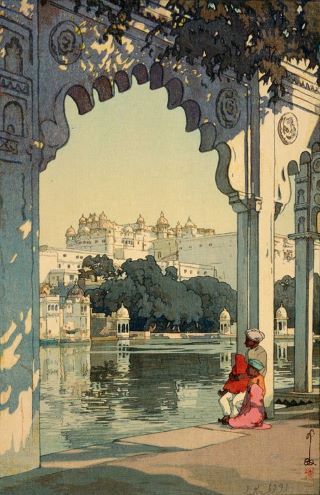

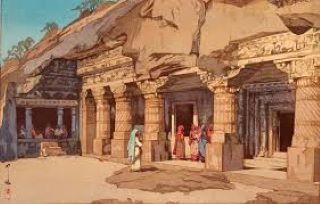

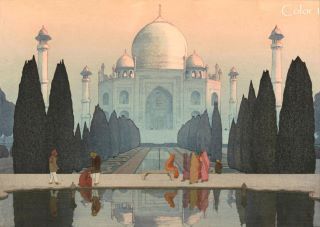

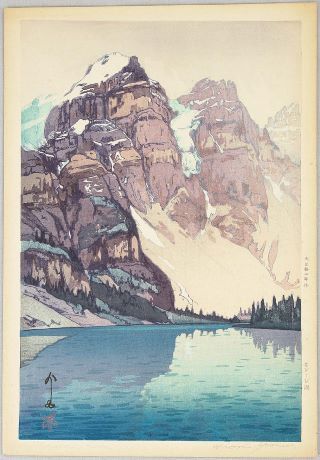

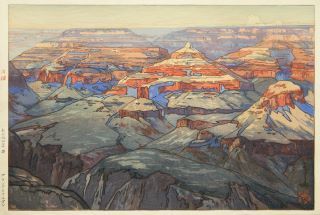

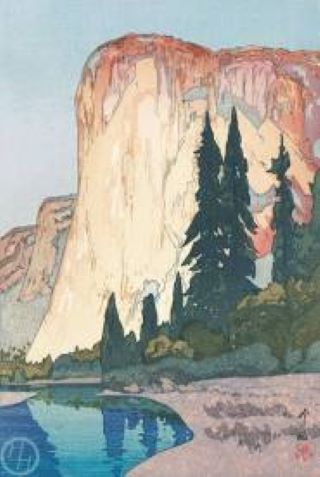

Yoshida is also notable in that he travelled the world extensively, and was particularly known for his images of landmarks around the world, but still done in traditional Japanese woodblock style. These included scenes of India, South East Asia, and National Parks in the United States, such as the Grand Canyon and Yosemite. 1

Hiroshi Yoshida was born on 19th September 1876 in the Fukuoka Prefecture, in Kyushu, in southern Japan. He was born Hiroshi Ueda, the second son of Ueda Tsukane, a schoolteacher from an old samurai family. But in 1891 he was adopted by his art teacher, Yoshida Kasaburo, and took his surname. I have not been able to discover why that was.

In 1893 he went to Kyoto to study painting, and the following year to Tokyo to join a private school; he also joined the Meiji Fine Arts Society. These institutions were teaching and encouraging Western-style painting, following the opening up of Japan in 1868 after 200 years of seclusion.

From 1899 to 1901 Hiroshi Yoshida made the first of many visits to the USA and Europe where he successfully exhibited, made artistic connections and sold his watercolours. He realised there was a good market in the West for his work, and again went to the USA, and Europe and North Africa in 1903-7, with his stepsister and fellow-artist Fujio, (who was the daughter of his adopted father), and whom he married on their return.2

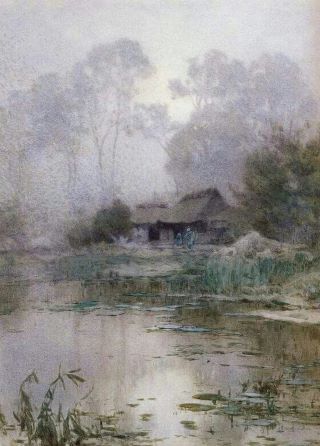

From then until 1920 he concentrated on oils and watercolours in the light, airy style he had learned in the West. 2

In 1920 Yoshida began to design woodblock prints for the publisher Watanabe Shozaburo (1885-1962), who was looking for a Western-style artist to design prints. But sadly, in September 1923, all the blocks for his prints and existing stock were lost in the Great Kanto earthquake and Watanabe’s shop was destroyed.

After this devastation, Hiroshi Yoshida left for the USA once more to raise funds for himself and for others; he toured through the western USA and realized that good prints were eagerly sought after in North America. On his return, he set up his own establishment to produce his designs in print form. From 1925 onwards Yoshida devoted his career almost exclusively to prints, supervising all aspects of their production to very high standards.2

The traditional process of creating Japanese woodblock prints was a cooperation of three strictly separated skills: the artist who designed the print subject, the carver and finally the printer and publisher. In contrast to this traditional approach, the sosaku hanga followers believed that the process of creating a print - design, carving, printing - should be performed by the artist himself. 3

In the Watanabe Print Shop, painters, carvers, and printers had equal input, with the publisher as the ultimate director. But Hiroshi believed that the painter, as the initial creator of the design, should have supreme authority, and that he, as the painter, should supervise the carvers and printers and in so doing direct every step of the production. This explains why he split away from his previous association with the Watanabe Print Shop: to have full control himself. He said that he needed to have more skills than the artisans he supervised to be able to fully use their talents, and so he strove constantly to expand his own knowledge of woodblock carving and printing techniques.2

Sometimes he printed on silk instead of paper and cut blocks from woods other than the standard cherry. He even used zinc plates for intricately detailed parts of fifty or more prints. His constantly inquiring spirit and creativity clearly can be seen in the techniques he used.2

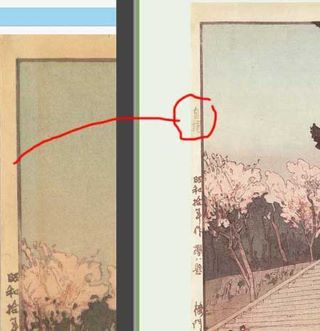

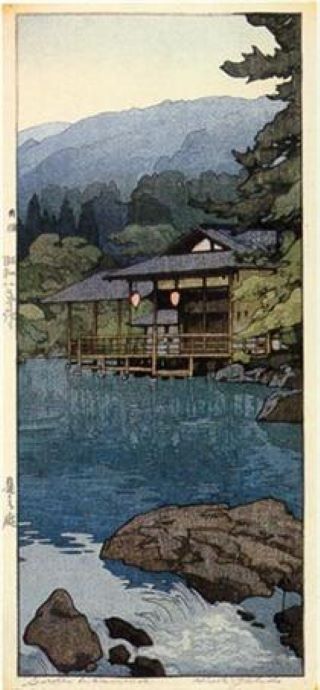

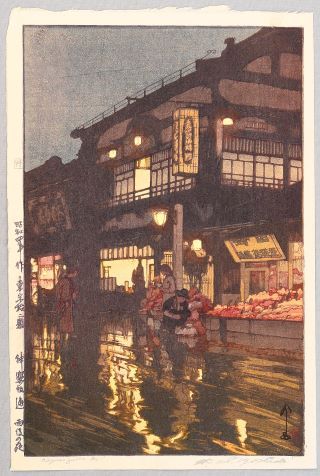

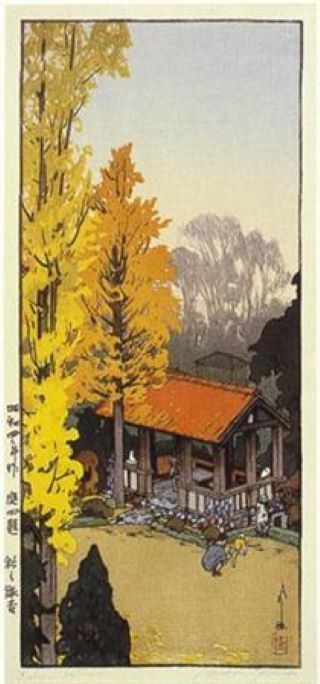

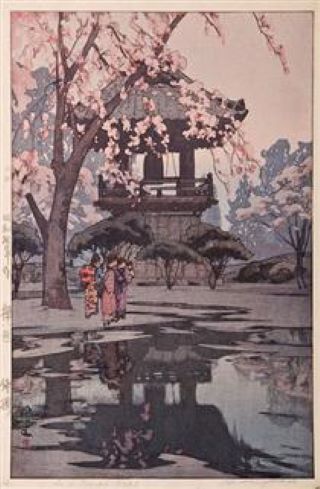

He was meticulous about the quality of the finished impressions. Only after he was satisfied that a print was unflawed in paper quality, registration, and colour did he stamp it with his seal and then sign it in pencil. This “self-print" notation (jizuri) was also a way to distinguish his prints from those of other artists and are more valuable today than those without this stamp. If you look closely in the left hand margin of the prints below you may be able to just make out his jizuri at the top of some of them.

Tomorrow we will return to look at how Yoshida's desire to experience Western culture first hand led to him combining the French Impressionist style with traditional Japanese woodblock printing techniques to achieve his own beautiful and unique print style.

Footnotes

With thanks to:

- Wikipedia

- myjapanesehanga.com

- artlino.com