Helene Schjerfbeck: "Intimacy and Interiority... What matters is at an angle"

Before I went to Cornwall I was treated to an exhibition in London of paintings by Finish artist Helene Schjerfbeck (1862 - 1946). Unfortunately she is not well known outside Finland but following this exhibition at The Royal Academy I am sure her popularity will flourish.

I found her oil paintings absolutely captivating. I talk about Receiving a Bolt of Lightning from special creative works and this artist delivered in spadefulls.

For me, the most captivating of her paintings was The Convalescent and not because it is in realistic terms just beautiful.

It is the exquisite expression on the child's face- her fragility has been captured by an artistic genius.

Helena Sofia (Helene) Schjerfbeck painted in a realistic style and is best known for her portraits, especially self portraits. According to Roberta Smith (New York Times, 7 Nov 1992):

Her work starts with a dazzlingly skilled, somewhat melancholic version of late 19th-century academic realism…it ends with distilled, nearly abstract images in which pure paint and cryptic description are held in perfect balance.

And Kate Kellaway describes Helena Schjerfbeck's artistic development as starting:

in the style of French naturalists such as Jules Bastien-Lepage before becoming an early modernist. She is sometimes described, according to the Ateneum’s chief curator and co-curator of the Royal Academy show Anna-Maria von Bonsdorff, as “Finland’s Munch”, though at the same time she is “individual – distinctively herself” and not as histrionic as her Norwegian counterpart. Royal Academy assistant curator Rebecca Bray suggests that through the “intimacy and interiority” in her work, she has more in common with the Danish painter Vilhelm Hammershøi, sharing his melancholic grace. ('Finland’s Munch: the unnerving art of Helene Schjerfbeck' by Kate Kellaway The Guardian, 7 Jul 2019)

I have seen 65 of her 1000+ paintings but today I will concentrate on her self portraits because through these we see, not only the gradual ageing of a woman, but the encroaching advances of illness as she succumbed to cancer: plus the evolution of her style. She painted her first portrait at 22 and her last at 83.

To quote from Kate Kellaway in her article - the art of Helene Schjerfbeck is unnerving.

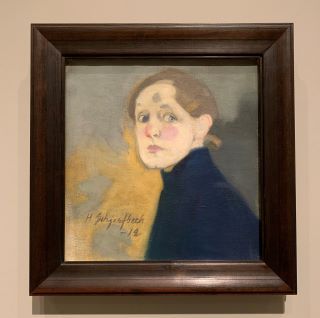

Commencing with three early self portraits Schjerfbeck's early self images are typical in form of the realism of the time though in the last of this group you can see her developing style emerging with, as seen in the 1885 portrait below, the soft palette of impressionism and the beginnings of her trade mark stance with the turned head and the slightly averted eyes.

For me the exhibition was not about the changing styles of Schjerfbeck but about the unpeeling of an artistic soul. To again quote Kate Kellaway: Schjerfbeck's self-portraits are an inquiry into mortality. They put her in the company of Goya, Rembrandt, Francis Bacon and Lucian Freud.

In the third portrait below we see emerging a shift towards a more expressive use of colour and gesture...which retains a spontaneous, convincing presence despite its bold stylisation. (Exhibition Label)

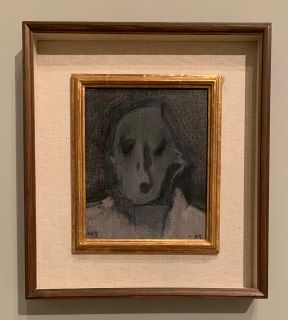

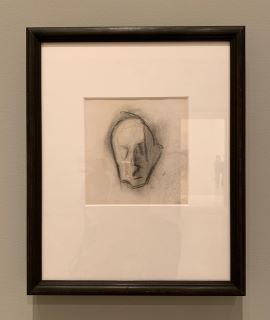

The self-portraits painted towards the end of her life, when she was dying of cancer in a sanatorium, show an understanding that a person is made up of everything they have ever been: she detects a youthfulness within age. (Kate Kellaway)

By the time she is painting Green Self-Portrait: Light and Shadows (1945), you can see that dust will soon follow: the skull beneath the skin is visible, the shadow of death. Through the dissolution of precise features, she paints a ghost of her former self. Kate Kellaway

The power in these paintings, says Bray, is the sense of “coming face to face with the interior of someone who is very ill and yet, at the same time, has a continuing will to work”. Their inwardness fascinates: Schjerfbeck frequently paints herself (and others) with an averted gaze – the eyes escaping towards the skirting board or into the corners of a room. The displaced intensity is reminiscent of lines from an Emily Dickinson poem: “I cannot live with You – It would be Life – And Life is over there – Behind the Shelf.” The sense is that what matters is at an angle, at one remove – elsewhere. (Kate Kellaway/theguardian.com)

Von Bonsdorff says Schjerfbeck never explained her preference for the averted gaze but believes it to be, in part, a further illustration of her need for privacy. In 1915, the Ateneum commissioned a self-portrait for an exhibition after a period during which she had felt ignored by the establishment. She was pleased to be the only female artist invited to participate (she was not a militant feminist but supported women’s suffrage – Finland was the first European country to give women the vote).

In the resulting painting (used on the poster for the Royal Academy show), she has daubed herself with rouge and positioned a vermilion paint pot beside her. Her name is on the canvas, Holbein-style. It is a wan, authoritative and unnerving piece. (Kate kellaway/theguardian.com)

Certainly the gazes from the self portraits are at first unnerving until I came to the realisation that, for me at least, what was happening was that Helene was gazing back at me, the viewer, imploring me from my perspective, to question and appreciate that all is not what it seems. We all have ambivalence and ambiguity in our personalities, opinions, perspectives and for me- the paintings of Helene Schjerfbeck are saying just that.

There is so much more to tell you about this remarkable artist who painted landscapes, still life and flowers as well as many portraits. And to my delight Helene visited and painted in St Ives, Cornwall- in fact it is believed that she is one of the very earliest of the foreign visitors to St Ives.

In 1887 Helene received a travel grant which she used to visit her friend Marianne Preindlsberger who had married artist Adrian Stokes in St Ives.

She was soon writing enthusiastic letters about the Cornish landscape: There are thousands of subjects here I would like to paint: the old fishing village down below, the new artists' town on the hills above, a couple of sandy beaches, the harbour with the boats, heaths and grassy pastures browned by the hot summer sun. Cornwall is the most beautiful place I have ever seen. (penleehouse.org.uk)

Helene returned to St Ives in 1889. Below is her Chickens Amongst Cornstooks (c.1887 Oil on panel) such a dramatic contrast to her self portraits as seen above.

When searching through the works of Helene Schjerfbeck I found two paintings of tulips: again such a stark contrast to her portraits. They are pretty and composed and convey a sense of peace not present in her portraits many of which exude stark anguish.

Tulips are such an important part of of lives; they are beautiful flowers and have symbolic significance in many cultures. My fellow bloggers Caroline and Jane have a Dutch heritage and you will be hearing more about tulips from Caroline very soon.