China's hidden century: illuminating the lives of individuals - Part Two

Court women were given jewellery for special celebrations such as marriage or birthdays, however the items remained the property of the imperial household. Hairpins were elaborate three-dimensional creations, with tassels and moving parts. Thumb rings (as shown on the right above) were worn by the Manchu archers and cavalrymen who commissioned rings to wear on the hand that pulled the bowstring, to allow for a snappier release during archery on horseback. In the late 1800s, their use spread to the merchant class and other elites. What had originated as a sign of Manchu ancestry also became an accessory, and a symbol of masculinity, for Han-Chinese men. 1

The various forms of Chinese paintings have long been admired.

Arguably the most impactful form of art in imperial China was not painting by educated elites, but mass-produced religious art. Images of gods and goddesses circulated in the form of woodblock prints. This extraordinary painting represents the Daoist goddess Magu, protector of women. The east-coast painter Ren Yun used gold extensively to catch the light, and the viewer's eye. 1

The wealthy enjoyed having their portraits created using all manner of techniques.

On the left above we have an Unknown Manchu Woman. The style of the painting suggests that this young woman was part of the imperial court. On formal occasions Manchu women wore three earrings in each earlobe as a marker of their ethnicity.1

On the right is Madam Li. Her husband's portrait was also in the exhibition though I missed getting a photograph of it.

There ancestral portraits were painted in a new style, inspired by photography, possibly while the couple were still alive. Their nephews, who were recognised cultural figures in the Foshan area near Guangzhou (Canton), inscribed the portraits, recording the details of a lifetime's achievements at the top of the paintings. Lu Xifu ran a successful business and his Buddhist wife managed his household, but little else is known of their lives. Such formal portraits were hung in a family shrine. 1

Painting and the impact of war

The lives of artists were scarred by the traumatic wars of the 19th century. Artis Tang Yifen and Dai Xi died in the Taiping Civil War (1851-64), fighting for the Qing government as soldiers and officials. For survivors, migration necessitated by warfare fragmented personal networks. Longstanding circles of patronage were severed. These were often focused in the old cultural heartlands of the Jiangnan region (south of the Yangzi River), so badly affected by the war. Yet upheaval could also catalyse innovation, as displaced artists developed new networks and supporters to survive. 1

Painting the natural world

The compositions of the artists represented in this section are fresh and powerful, strikingly different from earlier, more sentimental and idealised images of plants. Artists created innovative viewpoints for their compositions or exaggerated features to make their work stand out in a competitive market. Many developed a scientific interest in the natural world by directly observing nature, mirroring the trend for the empirical investigation of antiques.

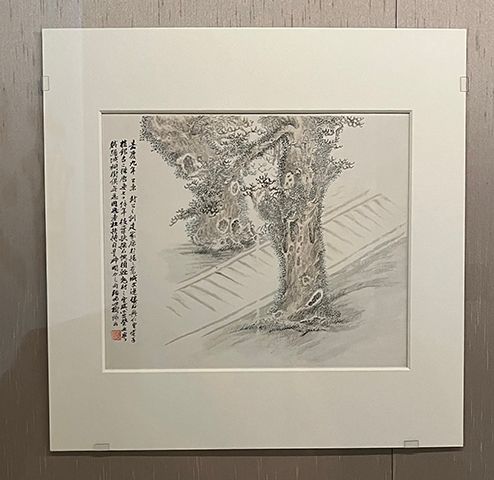

Wang Jun (1816-after 1883), Ten Sites Associated with Ruan Yuan

Scholar-official Ruan Yuan (1764-1849) dominated cultural life in his home city of Yangzhou, where he financially supported building and publishing projects. This album includes images of his family's temples and historic sites that he patronised. 1

Showing the trees that survived the Taiping invasion, and so demonstrating both desolation and resilience through adversity, this scene (above) is particularly evocative of the Taiping's devastation of southern China.1

And finally to conclude the showcasing of some of the items in the British Museum exhibition of China's Hidden Century we have a delightful painting by Ju Lian (1828-1904)

If you have time you might like to watch this video on aspects of the exhibition.

But before I leave today I must direct you to China OnLine Museum - which looks to be a most interesting site offering hours of browsing opportunities.