Spowers and Syme: Pioneers in modern art technique

In between the fascinating travel blogs of both Anne and Jane, we have been looking at some of the artists represented in the Know My Name initiative of the National Gallery of Australia.

We have looked at artists such as Hilda Rix Nicholas, Margaret Preston, Ethel Carrick Fox and Grace Cossington Smith who, whilst being contemporaries, didn’t appear to have been friends or even collaborators.

Today we return to present the changing face of inter-war Australia through the perspective of two other pioneering modern women artists - Ethel Spowers (1890-1947) and Eveline Syme(1888-1961) who were friends, and introduced a whole new medium to the world of modern art – lino cuts.

The unlikely collaboration of these two artists perhaps springs from the fact that they were each daughters of rival media families. Ethel Spowers’ father, William, was one of the proprietors of The Argus and The Australasian in Melbourne in the late 19th century and early 20th century. Eveline Syme’s father, Joseph Syme, was a part owner of The Age in Melbourne, beginning from 1879. (Melbournians will be very familiar with the name of David Syme, Eveline’s uncle. He is revered in newspaper circles. If you’d like to read more about him, click here).

But now back to modern art. Less than 2 years apart in age, both girls were students at Melbourne Grammar, and by indirect paths, both decided to study art. Eveline Syme returned to England to study classics at Newnham College, Cambridge, but as women were not granted degrees from Cambridge in her time, she returned to Melbourne to achieve an education degree in the early 1920s. Her association with her friend and other artists gave her the confidence to pursue her own artistic career, and she first exhibited her watercolours in 1924.

Ethel Spowers’ family were wealthy and cultured, and so, instead of working, Spowers was able to train as an artist at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School after her school years, between 1911 and 1917. She had her first solo exhibit in Melbourne at age 30, showing fairy-tale illustrations with another fairytale artist, Ethel Jackson Morris. She went on to have two more shows in 1925 and 1927, which confirmed her reputation as an illustrator of fairy tales.

Like many younger Australian artists at the time, both Syme and Spowers had dabbled in teaching themselves to make relief prints using a popular British book on Japanese printmaking techniques.2 These most commonly involved woodblock cuts.

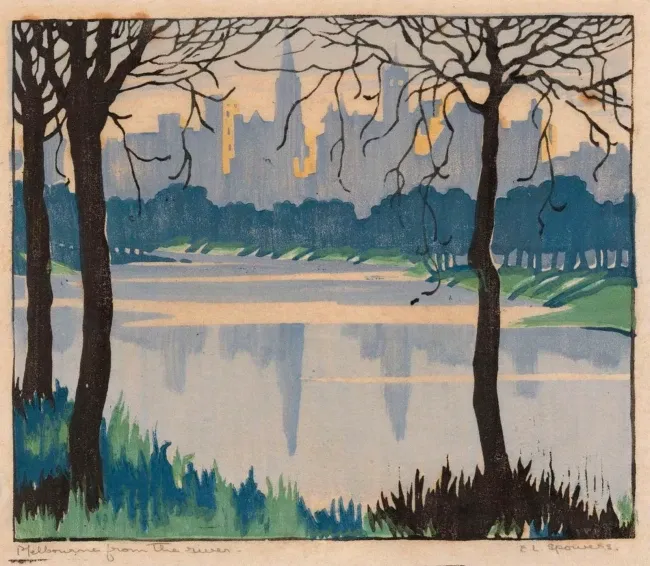

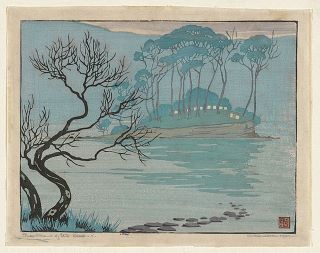

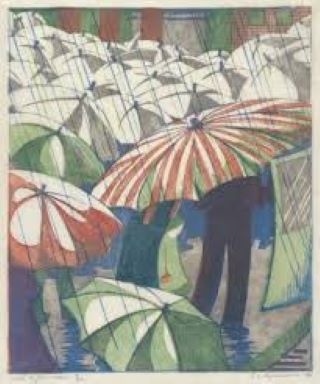

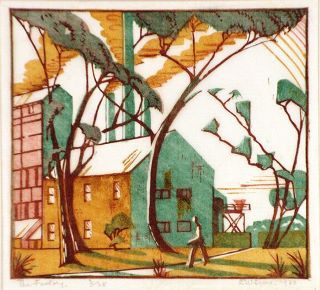

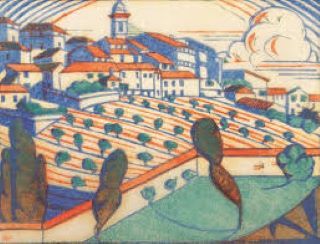

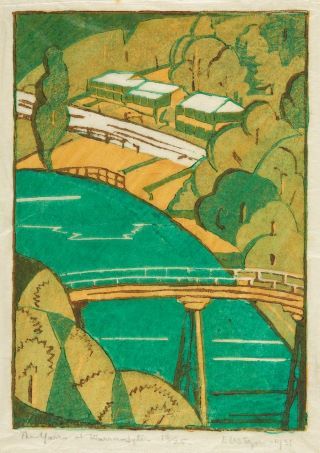

You can see the Japanese influence in these examples of early 1920s works by Ethel Spowers:

But in 1928–29 Eveline Syme happened to buy a book by the avant-garde English printmaker, Claude Flight, on how to make “lino-cuts” – prints using the cheap new flooring called linoleum. This inspired them both so much that they both enrolled at the Grosvenor School of Modern Art, in London, to learn more from Claude Flight himself, who ran the Grosvenor School with his friend, wood engraver, Iain Macnab. Further classes followed in 1931.

You may wonder what the difference is between a woodcut and a linocut?

Both are a type of relief print. Relief printing is when a piece of paper is “stamped” with ink from the top surface of the plate, commonly carved wood. A linocut uses linoleum instead of wood. As linoleum is a softer material than wood it is flexible and easier to carve. The lines of a linocut tend to be smoother and not as sharp or jagged as a woodcut.

Syme also studied with Cubist painter André Lhote in Paris to expand her knowledge of stylised geometric abstraction and colour harmony. For many progressive artists, including Australian students Grace Crowley, Anne Dangar, Dorrit Black and Edith Alsop, Lhote became the bridge between classicism and modernism.2

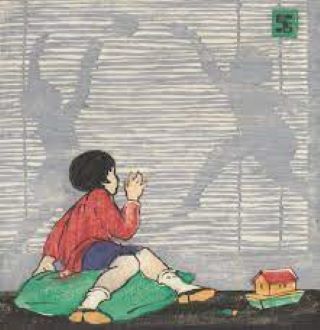

In the 1930s Eveline Syme’s linocuts attracted critical attention for their bold, simplified forms, rhythmic sense of movement, distinctive use of colour and humorous observation of everyday life, particularly the world of children, no doubt carrying over from her earlier work as a fairytale illustrator.

Ethel Spowers and Eveline Syme returned to the conservative art world of Australia. Their support and collaboration spurred them on to experiment with what they had learnt in London, and both became enthusiastic exponents of modern art in Melbourne. Syme demonstrated the colour linocut technique for the Arts and Crafts Society of Victoria and together they organised the first exhibition of linocuts in Australia.

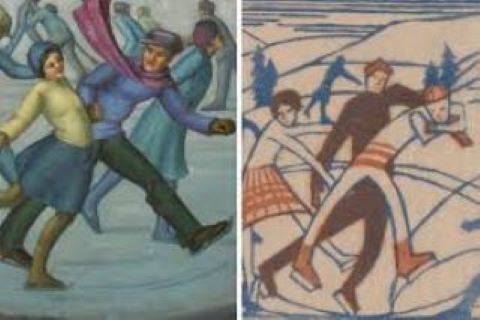

I think it is wonderful that, despite their close friendship and collaboration, both women developed different styles, which you can see in the following example depicting an ice skating scene:

Spowers, and Syme, along with Dorrit Black, promoted interest in the modern colour linocut in Melbourne and Sydney in the late 1920s and throughout the 1930s by exhibiting their own work, writing about Flight’s ideas and teaching his methods.2

In 1932, Ethel Spowers became a founder of The Contemporary Art Society, promoting modern art in Australia. Spowers also acted as an agent for the prints of Flight and other Grosvenor School artists in Australia, exhibiting impressions and taking orders for sales. Through these activities, the three artists each played a vital role as advocates for modernism in the inter war period in Australia.2

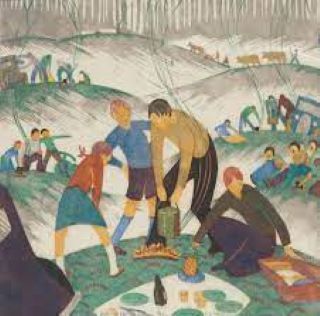

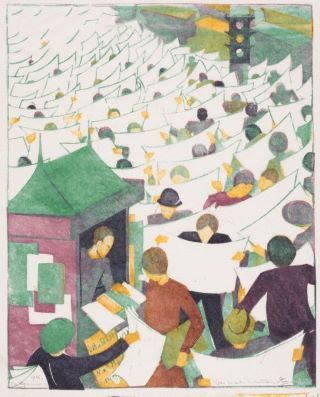

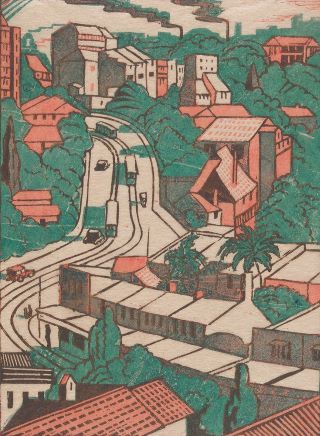

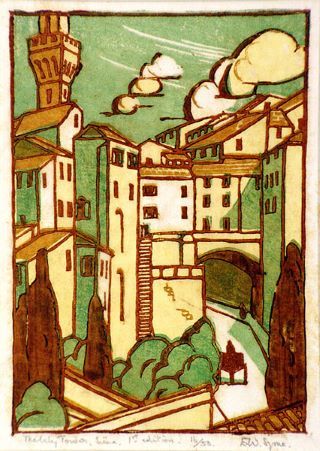

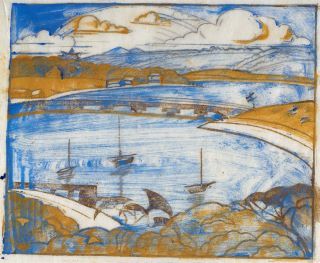

Here are a few more of both Spowers and Syme’s works, so you can see the difference in their styles. Let us know what you think of them!

Firstly, Ethel Spowers:

Secondly, works by Eveline Syme:

Interestingly, neither lady ever married or had children, and, due to their privileged backgrounds, were under no pressure to earn an income, so they were free to devote themselves to their art and the promotion of Modern Art as a concept. This was a considerable achievement, using a new medium in a very chauvinistic, male-dominated and controlled world of art.

Ethel Spowers died in Melbourne on 5 May 1947, after a long illness from breast cancer, aged 56. She was buried at Fawkner Memorial Park. A children's book illustrated by Spowers, Cuthbert and the Dogs, was published the year after her death. 1

The National Gallery of Australia holds 47 of her prints executed in the 1920s and 1930s. Her prints are also held in the National Gallery of Victoria and the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery, Victoria. The British Museum and the Victoria and Albert Museum purchased a number of her linocuts.1

Despite the loss of her friend and colleague in 1947, Eveline Syme remained active in art and women’s causes. She continued her association with The Contemporary Art Group and was involved in the drive to build a women's college at the University of Melbourne. She served as president of the University Women's College council in the 1940s. In fact, she left much of her estate to the University Women's College. 1 Late in life, she became a member of the executive committee of the National Gallery Society of Victoria.

Eveline Syme died in 1961, age 72. She was buried at Brighton Cemetery. Eveline was a founding member of the University Women's College at the University of Melbourne.

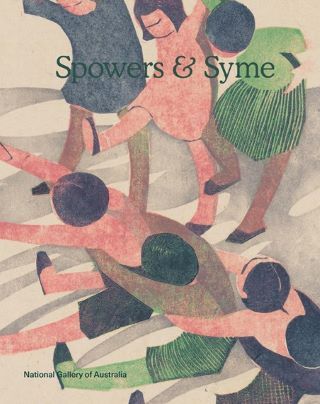

An exhibition called Spowers and Syme was shown at the National Gallery of Australia in Canberra, and in Geelong, Victoria over 1921 and 1922. There is an excellent article by John McDonald, who writes for the Sydney Morning Herald art column which provides more insight into these artists and their work. Click here if you’d like to read it.

I wish I’d seen the Spowers and Syme exhibition, but I didn’t. Luckily, there is now also a book which showcases their dynamic approach to lino and woodcut techniques, and prints and drawings whose rhythmic patterns reflect the fast pace of the modern world through everyday observations of childhood themes, overseas travel and urban life. 2

Footnotes

With thanks to

- Wikipedia

- National Gallery of Australia