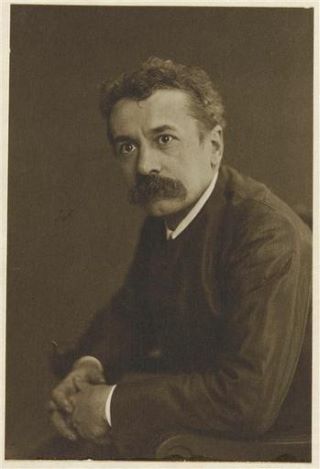

Rene Lalique, French glassmaker extraordinaire

You may be familiar with the distinctively opaque vases, statues or jewellery made by Rene Lalique, (1860 – 1945). His work is famous around the world and his Art Deco pieces and Art Noveau jewellery were particularly sought-after in the 1920s when these styles were all the rage. He also designed wide ranging items such as perfume bottles, chandeliers, clocks, and automobile hood/bonnet ornaments!

We recently featured another French Art Nouveau glassmaker, Emile Galle (click here if you missed it.)

It is interesting to note that Rene Lalique and Galle were quite similar in how they learnt their craft. Both spent some time in their childhoods in the countryside of northern France and were later very influenced by nature in both their designs and choice of colours. Both learnt sketching and drawing at school and at night school; and both furthered their education in Paris. Both also worked as apprentices to learn their techniques from the ground up.

Whilst Galle was some 14 years older than Rene Lalique, they were not colleagues, but certainly knew of each other. In fact, Galle is said to have called Rene Lalique “the inventor of modern jewellery”.

From age 14 to 16, Lalique attended evening classes at the Ecole Des Arts Décoratifs in Paris. He then went to London and spent two years at the Crystal Palace School of Art in Sydenham where he honed his skills in graphic design and his naturalistic approach to art further matured. When he returned from England, he worked as a freelance artist, designing pieces of jewellery for French jewellers such as Cartier, Boucheron, and others. In 1885, he opened his own business, designing and making his own jewellery and other glass pieces. After 1895, Lalique also created pieces for Samuel Bing's Paris shop, the Maison de l'Art Nouveau, which gave the Art Nouveau movement its name. 1

Rene was also a technical innovator, successfully introducing new materials, emphasizing their visual and tactile qualities. He opted to use many beautiful semi-precious gemstones such as opal, chrysoprase, onyx and jade rather than high value gems like diamonds, sapphires and rubies. He combined gold with ivory, horn, mother-of-pearl to give sculptural textures. He revived ancient enamel and glass techniques to add realistic details to insects and plants in his jewellery.2

Female figures with sensuous hair and diaphanous drapery, and flora and fauna, especially snakes or insects, were Lalique’s major inspiration in creating unique pieces of Art Nouveau jewellery.

Lalique’s fame extended even further after his Art Nouveau brooches and combs attracted a great deal of attention at the Paris International Exhibition in 1900. René Lalique then acquired an enviable clientele, including wealthy international aristocrats and socialites, patrons of the arts and stars of the theatre.

One such example was the famous French actress, Sarah Bernhardt, for whom he designed some of his finest creations. In the mid 1890s she wore some of Lalique’s jewellery on stage. Bernhardt later introduced Lalique to a wealthy Portuguese businessman, philanthropist and art collector, Calouste Gulbenkian, who commissioned 145 pieces from Lalique over a number of years. Many of these pieces can still be seen today in Gulbenkian’s museum of treasures in Lisbon, the Musee de Gulbenkian.

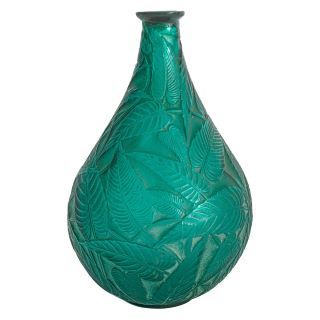

After this success, Lalique turned his hand to glasswork. By 1910 he had established a glass factory at Combs-la-Ville, France, and in 1918 he acquired a larger factory at Wingen-sur-Moder, in the Alsace region of France, with a grant provided by the government after World War One. An order for perfume bottles led him to develop that style of moulded glass with which he is generally associated: a style that celebrates the contrasts between clear and frosted glass. Sometimes patinas (surface coatings), enamels or areas of stained glass were added in relief, and occasionally with applied or inlaid colour. His relief decoration was produced by blowing into moulds or by pressing. His new designs shown at the Paris Exhibition, 1925, greatly enhanced his reputation. 3

After 1925, Lalique introduced a range of colours into his commercial lines. The yellow amber of the Bacchantes vase was made using iron oxides in the glass mass. The figure design was adapted and reused in other works. The Bacchantes theme echoes the Art Deco appetite for Classical imagery. 3

In 1928, he was chosen, among a number of other distinguished designers, to decorate the Côte d’Azur Pullman Express train carriages. The V&A holds one of the Lalique window panels, titled 'Blackbirds and Grapes', which was used as a divider between carriages.3

It's a wonderful example of his signature style of contrasted clear and frosted glass, don't you thnk?.

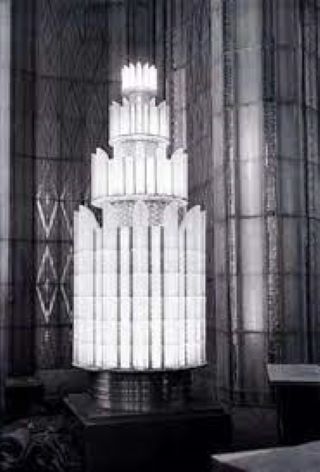

Lalique also designed the walls of lighted glass and elegant coloured glass columns which filled the dining room and "grand salon" of the 1930s ocean liner, the SS Normandie, as well as various interior fittings and decorations of St. Matthew's Church at Millbrook in Jersey, USA (known as Lalique's "Glass Church").1

Part of Lalique's genius was in producing innovative, usable art glass creations that became highly sought after by ordinary people, thus earning him a reputation as one of the most celebrated glassmakers in the world.

He died in Paris on 5th May,1945 and is buried at Le Pere Lachaise Cemetery in Paris. His son, Marc, continued to produce glass products in Lalique’s factory following his father's same style after his death, and his granddaughter was a glass maker as well. Lalique is still a brand making beautiful things today, but since 2010, Lalique has been owned by Swiss company Art and Fragrance.

If you would like to see more examples of Lalique, please click here.

If you would like to read more detail about Rene Lalique's life and work, please click here.

Footnotes

- With thanks to Wikipedia

- With thanks to Gold Arts.co.uk

- With thanks to The Victoria and Albert Museum, the V&A.