Unwrapping Egyptian Mummies

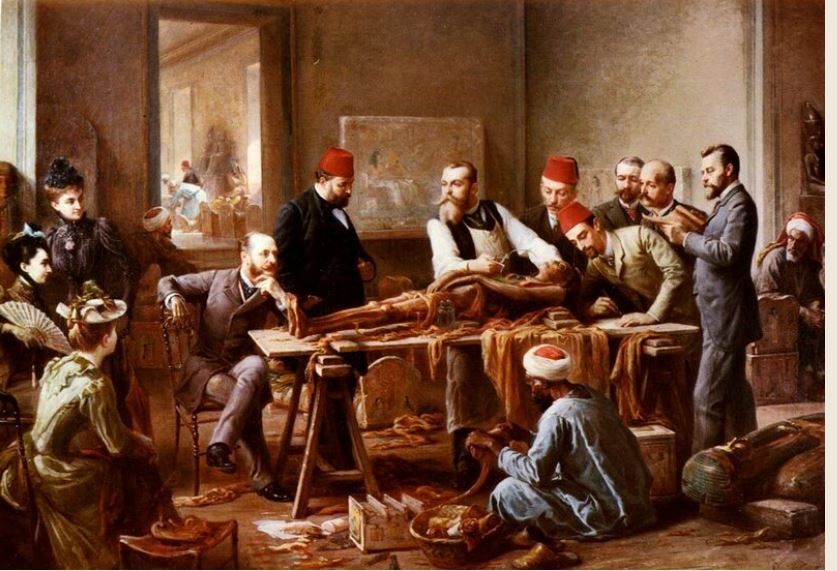

During my recent visit to the Chau Chak Museum at Sydney University in Sydney, I was fascinated by this painting - Examination of a Mummy by Paul Dominique Philippoteaux.

I could see a mummy was being unravelled and the label stated:

The painting documents a team from the French Egyptology Society unwrapping the mummy of a woman named Ta-udja-ra in the antiquities museum Giza.2

But who were the beautifully dressed ladies on the left taking a keen interest in the proceedings?

To my complete amazement a further label explained:

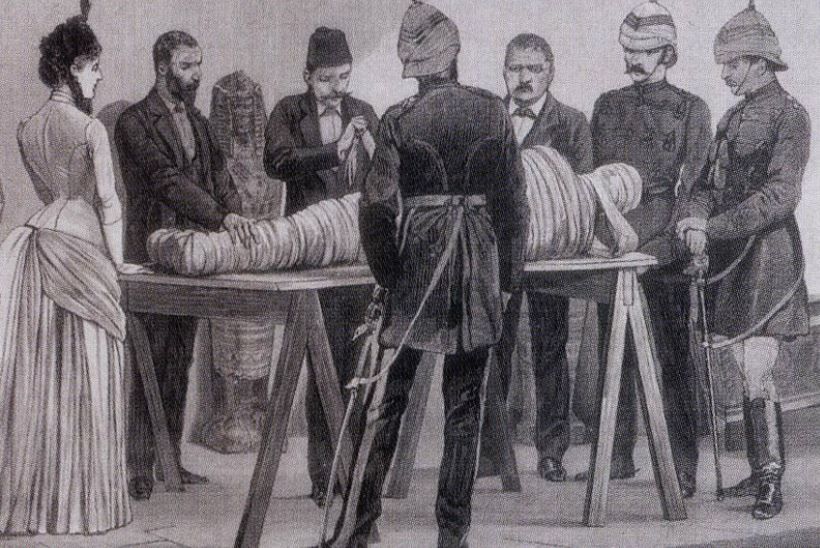

In the C19th, it became popular to unwrap mummies as entertainment, often for fee-paying crowds. These highly destructive events caused irreversible damage to mummified remains.

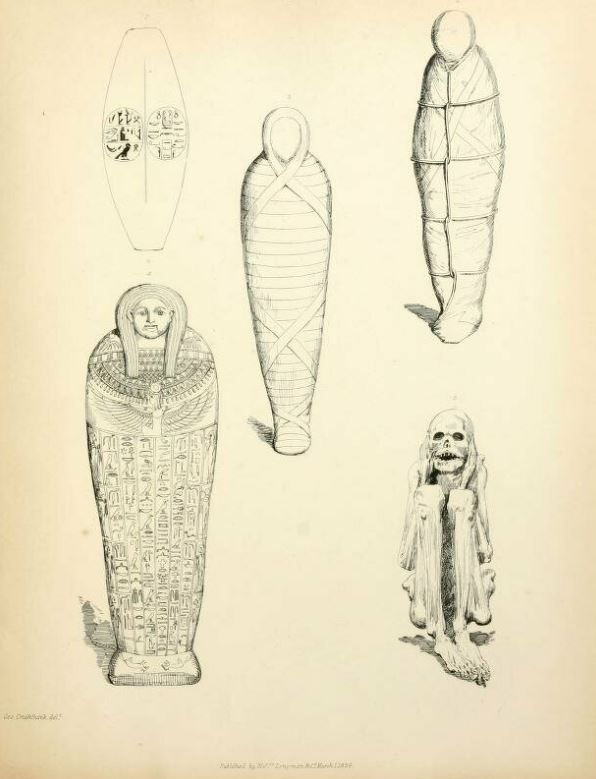

Mummies were also unwrapped by scholars seeking knowledge about the people they contained. The first royal mummies were unwrapped by Grafton Elliot Smith, a University of Sydney graduate who was appointed professor of Anatomy at Cairo in 1900. Elliot Smith investigated issues such as age at death, disease and dental health.2

It seemed so macabre but I wanted to know more! Further research on the website atlasobscura.com provided the following information:

If you were looking to have a great night out on January 15, 1834, Thomas Pettigrew’s sold-out event was definitely the place to be. The lucky Londoners who had managed to acquire a ticket for the Royal College of Surgeons that night, were looking forward to a rare sensation: before their eyes, Pettigrew was going to slowly unroll an authentic Egyptian mummy of the 21st dynasty: for science!

Mummy unrollings were only one symptom of the Egyptomania sweeping England in the 19th century. Europeans had been buying mummies since Shakespeare’s times to use them as medicine, pigment or even charms.1

Thomas Pettigrew was uniquely qualified to take this love affair with Egypt’s dead to the next level. A highly respected surgeon now focusing on his antiquarian interests, Pettigrew had just published his very well-received History of Egyptian Mummies (1834).

As a friend to many artists and authors – including Charles Dickens – he also knew how to spin scientific theory into fascinating spectacle. While he was not the first to unroll a mummy in front of an audience, he was the one to turn the procedure into a performance.

The recipe was guaranteed to succeed: mixing Egypt, science and the macabre proved irresistible to the Victorians. The same people who thought it vulgar to take off their gloves in mixed company, delighted in having a millennia old corpse divested of its wrappings in front of them.1

Thankfully, mummy unrollings fell out of favor with the scientific community as the idea of preserving ancient cultures rose in popularity.

Today we are blessed with incredible technology that allows for sophisticated methods which do not require mummies to be unwrapped.

The three mummified animals showcased in the video below — a cat, a snake, and a bird — remained shrouded in bandages, and mystery, for more than 2000 years. But a new 3D look inside is revealing deeper insights into how they lived and died.

Scientists utilized so-called micro–computer tomography (micro-CT) scanning, which creates 3D images by merging thousands of 2D x-ray projections from different angles. Micro-CT provides up to 100 times higher resolution than a typical medical CT scan, meaning the researchers could zoom in to uncover much finer details without damaging the delicate specimens.3

I am sure you are as surprised as I was that a fascination with one painting would take me on this captivating, if somewhat ghoulish journey into history.

Credits

1. atlasobscure.com

2. Chau Chak Museum

3. sciencemag.org