The evolution of "Still Life"

I recently read an interesting article by Rebecca Birrell The women artists who radically reclaimed still life posted 19 Aug 2021 on the artuk.org which got me thinking about how the genre of Still Life has evolved over hundreds of years, in fact thousands of years, and today remains a popular form of art amongst creators and buyers.

We can all easily identify a Still Life painting usually depicting inanimate objects such as flowers, food and even dead animals from the natural world with the addition of human made objects such as glasses, dishes, vases.

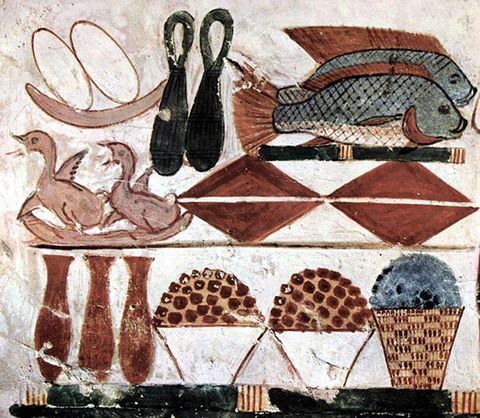

But did you know that the very first still life paintings were created by the Egyptians as early as the 15th century BCE?

Funerary paintings of food—including crops, fish, and meat—have been discovered in ancient burial sites. The most famous ancient Egyptian still-life was discovered in the Tomb of Menna, a site whose walls were adorned with exceptionally detailed scenes of everyday life.1

Ancient Greeks and Romans also created similar depictions of inanimate objects. While they mostly reserved still life subject matter for mosaics, they also employed it for frescoes, like Still Life with Glass Bowl of Fruit and Vases, a 1st-century wall painting from Pompeii.1

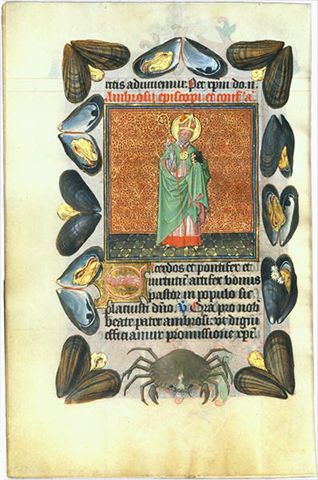

Still life continued in a different way during the Middle Ages where common objects were used in more a symbolic way as illustrations in borders on religious manuscripts. Below is a page from the Hours of Catherine of Cleves showing Saint Ambrose with a border of mussel-shells and a crab.

And also from the late Middle Ages we find most probably the first example of what we have come to accept as the style of a Still Life painting in a work by the Italian painter Jacopo de’Barbari painted 1504. The painting depicts a dead partridge, a pair of gauntlets with a cross-bow bolt holding the composition together. The painting was done in oil on a lime wood panel. 2

The Still Life floral arrangements we see so often today began to emerge early in the C17th from the Northern Renaissance artists such as Jan Brueghel the Elder▲ as shown below. The artists of this period began to be more interested in making their paintings more representative of real life and to emphasise the significance of everyday objects.1

While the Brueghels in Antwerp were developing expertise in painting floral arrangements, The Dutch Golden Age painters in Haarlem such as Pieter Claesz (c1597–1-1660) (below) were perfecting what is called vanitas painting.

Vanitas paintings are inspired by memento mori, a genre of painting whose Latin name translates to “remember that you have to die.” Like memento mori depictions, these pieces often pair cut flowers with objects like human skulls, waning candles, and overturned hourglasses to comment on the fleeting nature of life.

Unlike memento mori art, however, vanitas paintings “also include other symbols such as musical instruments, wine and books to remind us explicitly of the vanity of worldly pleasures and goods” (Tate).1

In his Vanitas with Violin and Glass Ball Pieter Claesz expounds a theorem of his art. The eye is guided to the various details by the lighting. The overturned glass, drained to the very last drop, seems to symbolize the briefness of worldly pleasures. The pocket watch is facing away from us and has its back open, as if someone had tried to fathom the mysterious nature of time. The violin, its bow lying obliquely across its strings, is angled diagonally towards the background. The instrument probably symbolizes the comparison and rivalry between the two arts of painting and music. Together with the book, the quill and its holder refer to writing, literature and the logocentric character of the vanitas.4

The glass ball is a fascinating, unusual motif. Reflected in its spherical surface is a self-portrait of the artist at his easel. Since he is present in effigie (i.e. in image), the artist does not need to place his signature on the panel, which consequently becomes a true autobiographical document: "pictor in tabula" - the painter is in the picture. The reflection of Claesz's self-portrait in his still-life may also be understood as a pointer to the fact that every painting conceals more than it reveals. In its reflective fragility, the glass ball also recalls a soap bubble, a conventional symbol in still-life painting for the fatal frailty of human life - man is like a soap bubble.4

Another Dutch Golden Age painter was Willem Claeszoon Heda (1593/1594 – c.1680/1682)who devoted himself exclusively to the painting of still life. He is known for his innovation of what is termed the late breakfast genre of still life painting.2

The Still Like by Willwm Claesz. Heda shows a table laid with oysters, a lemon, and beer invites the viewer to associate visual and culinary pleasure. But a closer look reveals broken glass and a cone of paper (intended to hold spices) torn from an almanac, both reminders of our swiftly passing days. Heda made a name for himself as an artist by achieving a variety of pictorial effects, such as the illusion of polished silver, glistening oysters, or reflective glass, while working almost exclusively in shades of gray.3

Tomorrow we will look at the changing perception of Still Life as it evolved in modern times.

▲Footnotes

I have made mention today of two members of the Brueghel Dynasty which when I last counted numbered something like 12 painters over several generations who just kept on inheriting the creative DNA from the first Brueghel - Pieter Bruegel the Elder (1525-30 to 1569). Very soon I am going to take you on a journey into the lives and art works of this most remarkable family.

Credits

1. mymodernmet.com

2. en.wikipedia.org

3. metmuseum.org

4. wga.hu