The lasting legacy of Utagawa Hiroshige

I recently watched an online lecture about some of the specific places that Claude Monet painted en plein air, as well as some other influences in his art.

The speaker said that Monet, along with other Impressionists such as Degas, Manet and Mary Cassatt were influenced by Japanese art, which had become a quite fashionable trend (called Japonsim). This developed in western Europe after the Meiji Restoration in 1868, when Japan opened up to trade and the Western world after 200 years of seclusion. (There is more detail in a previous post, 'Snapshot of Japanese Art' – Part 2 ).

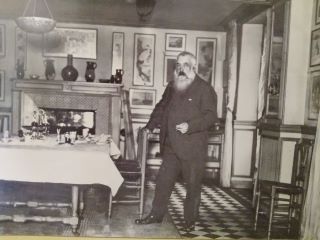

Monet collected many Japanese woodblock prints, some of which can be seen in his house in Giverny, which I was privileged to visit in September 2019:

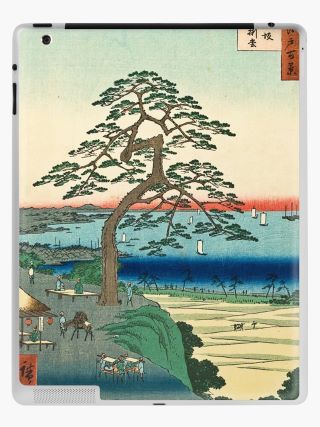

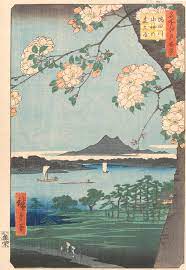

In particular, Monet collected and studied the compositions of the Japanese wood block printer Utagawa Hiroshige, who is considered the last great master of the ukiyo-e print process.

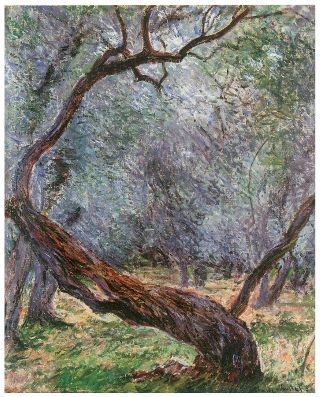

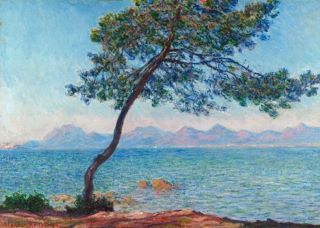

You can see this influence below in a few of Monet's paintings from the 1880s, against one of Hiroshige's prints:

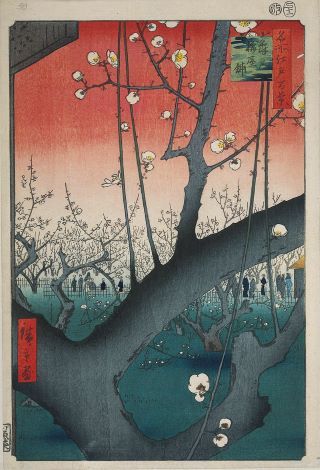

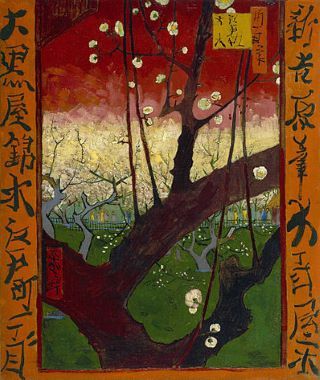

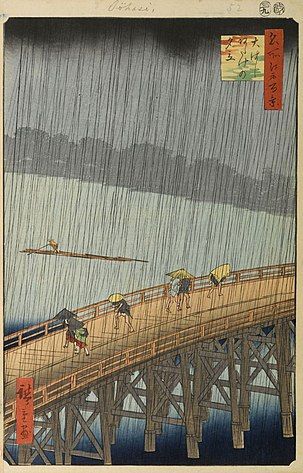

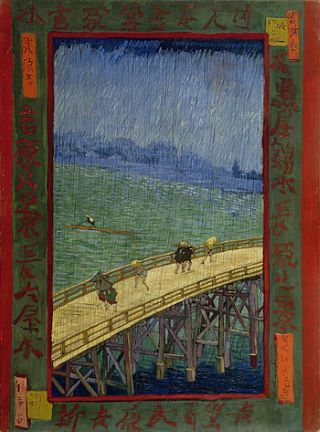

Vincent van Gogh even went so far as to paint copies of two of Hiroshige's prints from the series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo: Plum Park in Kameido and Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and Atake:

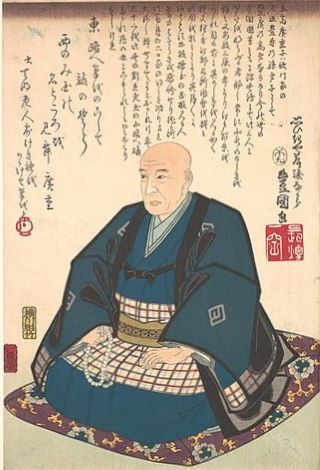

So, who was this influential artist? Utagawa Hiroshige was born as Tokutaro Ando in 1797, and began painting as a teenager. For reasons I've not been able to discover, he had several name changes as a youth: Jūemon, Tokubē, and Tetsuzō.

In 1811, young Hiroshige entered an apprenticeship with the celebrated artist Utagawa Toyohiro. After only a year, the artist name of Hiroshige was given to him.

At different times he has signed his work under the professional names of Utagawa Hiroshige and Ichiyūsai Hiroshige, as well as using his own previous names.

Hiroshige appears to have been influenced by the landscape scenes of Katsushika Hokusai (known as Hokusai), who was an early contemporary of his.

We are all familiar with the Great Wave off Kanagawa, which is one of the prints in Hokusai’s series of the Thirty-six views of Mt. Fuji, which had just been produced at the time. (There is more information about that print in a previous post.)

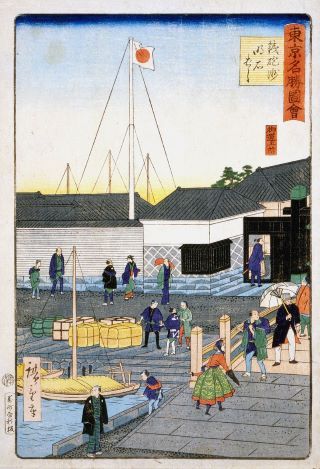

The subjects of Hiroshige’s work were atypical of the usual ukiyo-e genre, where the usual subjects were beautiful women, popular Kabuki actors, and other scenes of the urban pleasure districts of Japan's Edo period (1603–1868).1

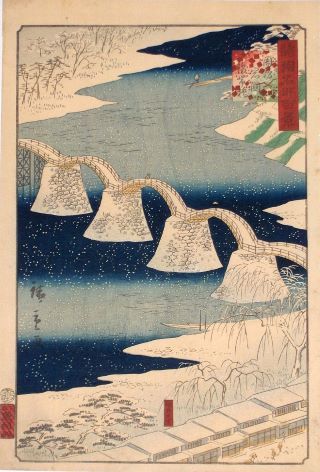

Instead, Hiroshige also began to produce horizontal-format landscapes in a series like Hokusai. He is best known for The Fifty-three Stations of the Tōkaidō (1832) and for his vertical-format landscape series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (1848 – 1858). Other well-known series are Eight views of the Edo environs (1834) and the Sixty-Nine Stations of the Kiso Kaido Road(1835 – 1842). (In this context “stations” refers to halting places along on a long route on foot or horseback, such as the trip from Tokyo (Edo) to Kyoto.

Subtle use of colour was essential in Hiroshige's prints, often printed with multiple impressions in the same area and with extensive use of bokashi (colour gradation), both of which were rather labour-intensive techniques. 1

You might like to watch the following short AnArt4Life video giving a few examples of Hiroshige’s prints from these series:

Hiroshige was prolific in the number of prints that he produced, particularly in the many “series” mentioned above. (As an aside, perhaps it was these series of multiple views that influenced Monet to produce his own various "series" too, such as the 53 views in his Haystack series, the 48 waterlilies, or the 31 views of the Cathedral at Rouen!? An interesting idea!)

It is thought that Hiroshige’s prolific output of printmaking stemmed from the fact that he was always poorly paid for his work, and particularly for each series of prints. Sadly, (like some of the Impressionists also), he didn't enjoy any degree of financial comfort throughout his whole life, right up until his death on 12th of October 1858, aged just 61.

He left a farewell poem saying:

I leave my brush in the East,

And set forth on my journey.

I shall see the famous places in the Western Land.

(The Western Land in this context refers to the strip of land by the Tōkaidō between Kyoto and Edo, but it does double duty as a reference to the paradise of the Amida Buddha). 1

For scholars and collectors, Hiroshige's death marked the beginning of a rapid decline in the ukiyo-e genre, especially in the face of the westernization that followed the Meiji Restoration of 1868. 1

Nevertheless, attraction to his work has lived on, with many other high profile collectors in addition to the Impressionists. Architect Frank Lloyd Wright was an enthusiastic collector of Hiroshige's prints, including those of The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tōkaidō. In 1906, he staged the first ever retrospective of Hiroshige's work at the Art Institute of Chicago, describing them in the exhibition catalogue as some of "the most valuable contributions ever made to the art of the world.” 1

If you are interested, other posts on Japanese art and culture by the AnArt4Life Blog team can be found under the Japan tag, in our website TagCloud.

Footnotes

- With thanks to Wikipedia.

- With thanks to hiroshige.org.uk for the video images.