Marie Bracquemond: Successful Against Great Odds - Yet Almost Unknown!

Before I start the blog today Anne has asked me to welcome our latest subscriber PP of Carlton. Thank you for joining up and we hope you enjoy our posts. Julie

I was lucky enough to visit the Musee D’Orsay in Paris, in September last year. The Musee D’Orsay holds the largest number of Impressionist paintings in the world, on the 5th floor.

But whilst there were any number of iconic paintings to mesmerise the viewer, by Monet, Degas, Renoir, Pissaro, Seurat, Van Gogh, Manet, Sisley and more, there was one that stood out to me.

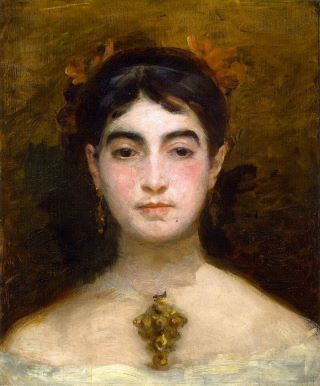

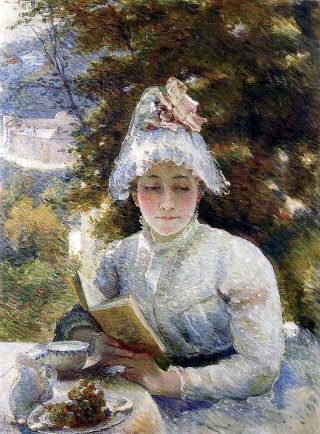

It is called “Lady in White” by Marie Bracquemond. I was captivated by the swirl of the soft, diaphanous ruffles of the beautiful dress.

Even these photos do not do justice to the brilliant white, yet delicate folds of the skirt, so beautifully arranged. I wanted to investigate why I had never heard of Marie Bracquemond, and where she fitted into the world of the Impressionists.

There are many similarities between Marie and Berthe Morisot, who we featured in an earlier blog Berthe Morisot- a versatile artist in a man's world.

But despite the similarities, and the almost parallel course of their lives as artists in a man’s world, (there was only a couple of months between them in age), Marie did not enjoy the same level of privilege, parental means or support of her husband. And yet, she was successful enough to have her work exhibited at The Salon a number of times, starting in 1857 at only age 16.

Largely from the source of Wikipedia, I have discovered that Marie Bracquemond was born Marie Anne Caroline Quivoron on 1 December 1840 in Argenton-en-Landunvez, near Brest, Brittany. She was the child of an unhappy arranged marriage, and her father died early in her childhood. Her mother quickly remarried and the family then led an unsettled existence, moving numerous times. Marie had one sister, Louise, born in 1849.

Even though she was born into the working class where very few luxuries could be afforded, Marie Bracquemond began painting lessons in her teens. She progressed to such an extent that in 1857 she submitted a painting of her mother, sister and old art teacher to The Salon which was accepted.

She was then introduced to the neo-classical painter, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres. As a student in his private Parisian studio, she wrote that, “The severity of Monsieur Ingres frightened me… because he doubted the courage and perseverance of a woman in the field of painting… He would assign to them only the painting of flowers, of fruits, of still lives, portraits and genre scenes. … I wish to work at painting, not to paint some flowers, but to express those feelings that art inspires in me.” (en.wikipedia.org)

Despite this artistic suppression, the critic Philippe Burty referred to Marie as "one of the most intelligent pupils in Ingres' studio".

She later left Ingres' studio and began receiving commissions for her work, including one from the court of Empress Eugenie for a painting of the Spanish writer Cervantes whilst held captive in a Turkish prison. Unfortunately, I have not been able to locate the commissioned painting.

Bracquemond's work for Empress Eugenie was evidently well accepted, because Marie was then asked by the Count de Nieuwerkerke, the director-general of French museums, to make important copies in the Louvre.

Whilst I could find no reference to Marie and Berthe Morisot ever meeting, Berthe and her sister were also engaged to make copies of the Old Masters in the Louvre at around the same time, so very possibly they did meet there. They also both exhibited at The Salon at around the same time, so they must have known each other, but don’t seem to have been close friends.

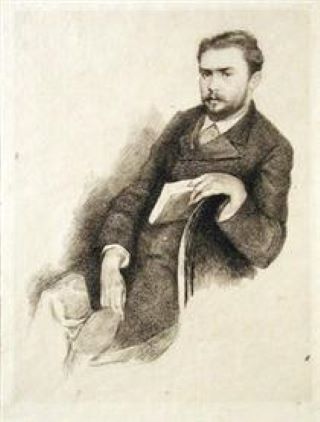

It was while Marie was copying Old Masters in the Louvre that she met Félix Bracquemond, who fell in love with her and from then on, she and Félix were inseparable. Felix was a painter, etcher and engraver, and became very interested in Japanese art, pottery design and print making. They were engaged for two years before they married on 5 August 1869, despite her mother's opposition. Felix taught her to sketch, and she used sketches to compose her paintings, as well as stand alone pieces.

In 1870, Marie and Felix had their only child, Pierre. Similarly, Berthe Morisot had just the one child, Julie Manet, who we featured in our blog Julie Manet – A box seat to the lives of the Impressionists.

Much of what is known of Marie’s personal life comes from an unpublished short biography by her son, entitled “La Vie de Félix et Marie Bracquemond.” (Coincidentally, Berthe’s daughter, Julie, also recorded life with the Impressionists in a published diary).

Between 1887 and 1890, under the influence of the Impressionists, Marie Bracquemond's style began to change. Her canvases grew larger and her colours intensified. She moved out of doors (part of a movement that came to be known as "en plein air"), and to her husband's disgust, Monet and Degas became her mentors.

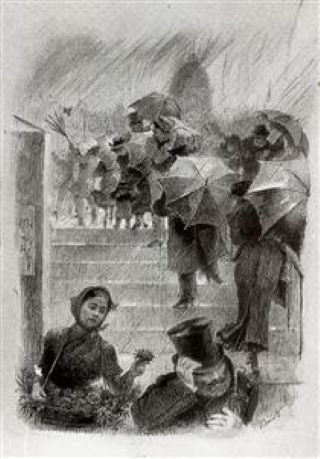

We can perhaps see some degree of Monet’s influence in these two works of “a lady with an umbrella”, one by Marie, on the left, and the other by Monet, on the right.

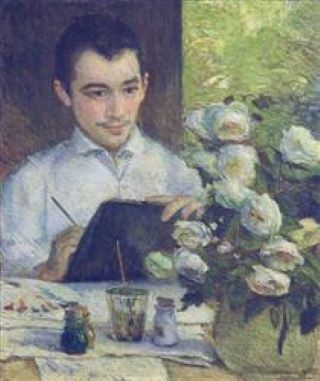

Many of Marie's best-known works were painted outdoors, especially in her garden at Sèvres. One of her last paintings was The Artist's Son and Sister in the Garden at Sèvres.

By the 1880s, Marie had joined the inner circle of the Impressionists and had participated in their exhibitions in 1879, 1880 and 1886 and had some of her works featured in La Vie Moderne in 1879 and 1880.

In 1886, Félix Bracquemond met Gauguin through Sisley and brought the impoverished artist home. Gauguin had a decisive influence on Marie’s use of colour and boldness of strokes.

However, her husband Felix was becoming more and more critical of her work. He disliked the Impressionist Movement and was unhappy that his wife’s style had moved so much in that direction. And yet, Felix had a continuing involvement with the group of Impressionists. He helped them with etching, and encouraged artists such as Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas and Camille Pissaro to participate in his revival of printmaking. It is a great shame that he could not embrace his wife’s

direction, even if his own interests lay in other fields of the arts.

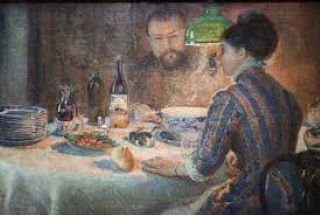

Under the Lamp (Credit: WikiArt.org, Public Domain)

According to their son, Pierre, Felix actively resented her work and her success. Marie Bracquemond was dominated by her husband, and, in 1890, she gave in to the constant friction and unrelenting badgering from her husband and almost completely stopped painting and exhibiting. Sadly, her career was all but buried, though she herself remained a staunch defender of Impressionism throughout her life. In defence of the style, she said, "Impressionism has produced ... not only a new, but a very useful way of looking at things. It is as though all at once a window opens and the sun and air enter your house in torrents."

By comparison, artists such as Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt had both the financial means and the support and encouragement of their husbands to enable their careers to flourish, despite the difficulties of being women artists in a man's world.

Most of Marie’s work is held in private collections, and is not much seen in the public domain. Due to this and the efforts of her husband to curtail her career, she is often omitted from art books on Impressionism. She has therefore remained relatively unknown, despite being described as one of "les trois grandes dames" of Impressionism, alongside Berthe Morisot and Mary Cassatt.