Sculptor: Rachel Whiteread

Today we are going to take a closer look at the artist Rachel Whiteread(1963-). I hope you read the article a couple of days ago about her temporary public sculpture House. In essence, she is expressing an interpretation of space, negative space and the contents therein, be they associated with a building or an object within a building.

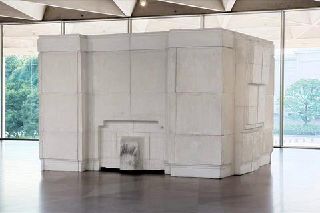

The first monumental sculpture that brought Rachel Whiteread recognition was Ghost (above), created in 1990. Ghost is a plaster cast of the interior space of an ordinary room, shown at the Chisenhale Gallery, London. Details of the fireplace with its gas fire, door and window impressions and traces of wallpaper and flakes of colour from the paintwork held the memory of the place. From this Whiteread developed a practice that concentrated on negative space and gave concrete materiality to overlooked objects from the everyday. (sculpture.org.uk)

Whitebread is the artist who created the Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial in Vienna which resembles the shelves of a library with the pages turned outwards.

The Judenplatz Holocaust Memorial is also known as the Nameless Library and stands in Judenplatz in the first district of Vienna. It is the central memorial for the Austrian victims of the Holocaust. The memorial is a steel and concrete construction with a base measuring 10 x 7 meters and a height of 3.8 meters. The outside surfaces of the volume are cast library shelves turned inside out. The spines of the books are facing inwards and are not visible, therefore the titles of the volumes are unknown and the content of the books remains unrevealed. The shelves of the memorial appear to hold endless copies of the same edition, which stand for the vast number of the victims, as well as the concept of Jews as People of the Book. The double doors are cast with the panels inside out, and have no doorknobs or handles. They suggest the possibility of coming and going, but do not open. (Wikipedia)

The memorial represents, in the style of Whiteread's empty spaces, a library whose books are shown on the outside but are unreadable. The memorial can be understood as an appreciation of Judaism as a religion of the book; however, it also speaks of a cultural space of memory and loss created by the genocide of the European Jews. (Wikipedia). Their stories are locked in our hearts forever.

Whiteread's Untitled Monument stands in Trafalgar Square, London. It is a transparent resin cast of the actual plinth, standing upsidedown and 14ft high.

Its beauty is entirely sensuous. When the light shines through the clear resin, it changes colour from cold grey or clear blue, depending on whether the day is overcast or sunny. Because it is as clear as an ice cube, it absorbs all its light and movement from the world around it. (The Telegraph)

Embankment is a rather different creation by Whiteread.

In a sense, Rachel Whiteread’s sculpture Embankment began with an old, worn cardboard box. She found it in her mother’s house shortly after she died. Whiteread was going through her mother’s belongings when she came upon a box she remembered well. It had had many lives: it used to reside in her toy cupboard next to piles of board games, and at one point was filled with Christmas decorations. Over time its sides started to collapse, the printed logo on the outside faded, and the lid came to shine with the traces of all the Sellotape used to bind it up over the years. (tate.org.uk)

Although the inspiration for EMBANKMENT came from the single box she found in her mother’s house, Whiteread selected a number of differently shaped old boxes to construct the installation for the Turbine Hall. She filled them with plaster, peeled away the exteriors and was left with perfect casts, each recording and preserving all the bumps and indentations on the inside. They are ghosts of interior spaces or, if you like, positive impressions of negative spaces. Yet Whiteread wanted to retain their quality as containers, so she had them re-fabricated in a translucent polyethylene which reveals a sense of an interior. And rather than make precious objects of them, she constructed thousands. (tate.org.uk)

There is a small white shack on the lawn in front of Tate Britain. It looks exactly like the very thing it is, namely the concrete cast of a chicken shed. The windows are blind and the door could never open to let the birds out, for the object is a solid block, heavy and impenetrable, unlike the airy structure it replicates. And yet it is still, first and last, a chicken shed. (the guardian.com)

Or is it? The art of Rachel Whiteread turns things inside out. This piece – hailed as a major new work at Tate Britain, though it’s anything but, and the artist calls it “shy” – is a cast of the space inside the shed. There’s a clue in the fact that the window frames are indented, instead of standing out. But so what? The object on the lawn – literal, stolid, untranslated – retains the form of the shed. It is a sculptural tautology. (the guardian.com)

Whiteread (born 1963) has been casting these so-called “negatives spaces” for three decades. The original idea comes from the US artist Bruce Nauman, whose "A Cast of the Space Under My Chair" (1965-8) spells out the method, if not the varying effects. (the guardian.com)

Whiteread has gone further, casting the innards of a hot-water bottle and a mattress; the undersides of a table, the space behind a fireplace or surrounding a bath. Her works run from the modest to the monumental – most famously the interior of an entire house – cast in plaster, resin, concrete or rubber, occasionally in metal (mundane) and lately in papier-mache (actively hideous). Everything she makes balances the possibility of poetry against the risk of banality. (the guardian.com)

Our examination of the concept of House, Home and the Space therein will be continued tomorrow.

To emphasise the fickleness of the art world, in the same year (1993) that Whiteread won the Turner Prize for best young British artist she was also given the K Foundation art award for the worst British artist. The lesson being: Follow your passion and try to ignore the critics.