Mexican Muralism Movement

I could not resist the alliteration offered by a headline for today's blog but what has been even more exciting is reading about the Mexican Muralism Movement which I have found enlightening. As one of my sons-in-law is Mexican I dedicate this post to him. We will get onto the Mexican Muralist Diego Rivera very soon.

People have been creating murals since women learnt how to draw on cave walls. Yes, it is now believed that the majority of the cave muralists were women which makes sense as the men would be out hunting, fishing and fighting and doing other important man stuff . Left at home with all the cavework completed for the day, the women turned their hands to painting. And it was their hands that gave archaeologists the information about who painted the early murals as in many cases they left hand prints.

Below is a 2,500 year old cave painting of a Man Seated on Throne, Oxtotitlan site, Olmec Culture, Middle Formative Period, BC, from the Cerro Quiotepec Mountain situated southwest of Cruz Chica, Mexico.

Mexican muralism was the promotion of mural painting starting in the 1920s, generally with social and political messages as part of efforts to reunify the country under the post-Mexican Revolution government. It was headed by "the big three" painters, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. From the 1920s to about the 1970s many murals with nationalistic, social and political messages were created on public buildings. This started a tradition which continues to this day in Mexico and has had an impact in other parts of the Americas, including the United States, where it served as inspiration for the Chicano art movement. 1

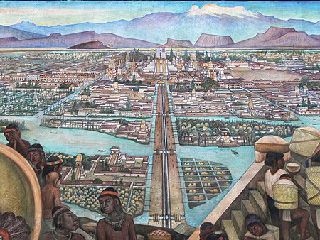

Below is a mural created by Diego Rivera showing the pre-Columbian Aztec city of Tenochtitlán. It is housed in the Palacio Nacional in Mexico City.

The Mexican Muralist movement brought mural painting back from its staid retirement in the history of ancient peoples as a respected artistic form with a strong social potential. With it, a rich visual language emerged in public spaces as a means to make art accessible to all. It provided an opportunity to educate and inform the common man with its messages of cultural identity, politics, oppression, resistance, progress, and other important issues of the time. It was a fiercely independent movement; many of its early artists rejecting external influences and used this new, vast, and freeing medium to achieve personal expression. This movement proved that art could be a valid communication tool outside the confines of the gallery and museum.2

Juan Cordero (1844-1921) was the first Mexican mural painter to use philosophical themes in his work during the mid 19th century. He mostly worked with religious themes such as the cupola of the Santa Teresa la Antigua, Mexico City which is shown below.

Cordero also painted a secular mural at the request of Gabino Barreda at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria but apparently it has disappeared.

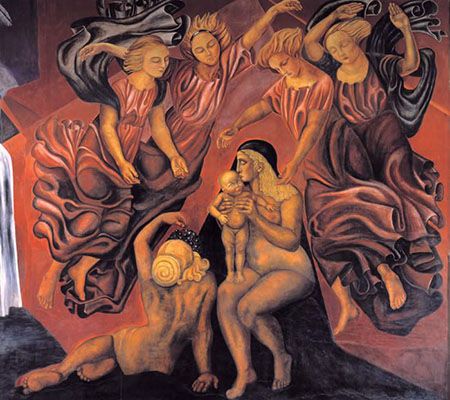

Turning to look a little more closely at José Clemente Orozco, below is one of Orozco's earliest frescoes, painted in 1923-24 for the ground floor of the National Preparatory School (ENP) in Mexico City. Maternity depicts a mother and child; it resembles Renaissance depictions of Mary and the infant Jesus, with the exception of the conspicuous nudity of the mother.3

Following the Mexican Revolution, the new government encouraged the production of public art to promote a nationalist program of unity, of the concept of an integrated populace or "Mexicanos." However, Orozco's use of overtly European figures seems to challenge the assertion by an increasingly authoritarian government that equality had been achieved. In this work, the beauty standard is European rather than indigenous. Here we see Orozco subtly critique the very institution that commissioned him for the work.

This particular mural is of immense value because it is the only surviving one of Orozco's earliest frescoes, as most were destroyed by conservative students at the ENP while others were demolished by Orozco himself. In fact, a group of Catholic women misinterpreted the secular meaning of Maternity, thought it sacrilegious, and attacked it.3

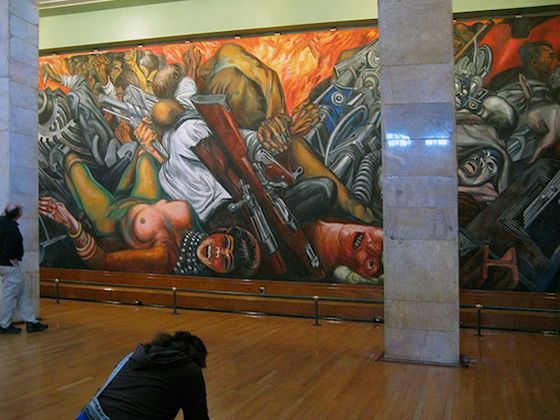

Three years later in 1926 Orozco returned to the ENP and painted The Trench (below) .

The Trench is very different from Orozco's earlier works. Here he paints in a modernist style in which forms are less modeled, line is expressive, and the palette reflective of the dark, emotional content of the mural.

The Trench depicts soldiers fighting in the Mexican Revolution. The three fallen, faceless men form a cross. The sharp diagonal of the composition and the vivid red of the background convey the scene's drama. Due to Orozco's new interest in modern art, with its representations of space and time as mutable and relative, the three men could be interpreted as a single soldier depicted in different moments in time.3

And below is a detail from Destruction of the Old Order painted by Orozco in 1926 and also housed in the National Preparatory School, Mexico City.

I was also able to locate a partial view of one of Orozco's murals in situ. Below you can see a partial view of Catharsis painted in 1934 and hangs in the Museum of the Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City.

David Alfaro Siqueiros (1896-1974) was a Mexican social realist painter, best known for his large murals in fresco. He was a member of the Mexican Communist Party, and a Stalinist and supporter of the Soviet Union who led an unsuccessful attempt to assassinate Leon Trotsky in May 1940.4

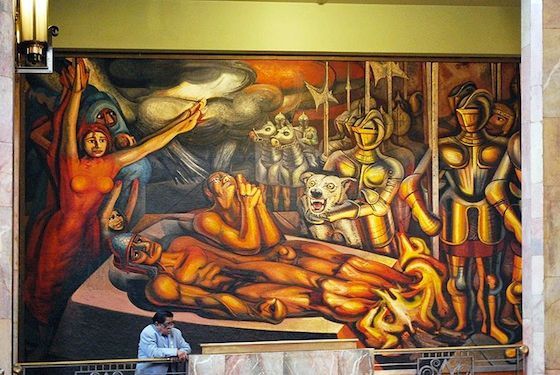

This is part of Siqueiros' mural Torment and Apotheosis of Cuauhtémoc created in 1950-51 and hangs in the Museum of the Palace of Fine Arts, Mexico City.

Siqueiros explores the violent period of the Conquest. In this mural Spanish soldiers torture the Mexican tribal leader for information on the location of the treasure they seek. The Mexican motherland, symbolized by the blood-stained female figure, stretches her arms protectively over his still figure. Siqueiros’ penchant for sinewy limbs, showcased in the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) murals and exemplified here in the bodies of Cuauhtémoc and his praying companion, underscore the tension in this encounter.5

At the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM) in Mexico City visitors enter the rectory (the main administration building), beneath an imposing three-dimensional arm emerging from a mural (below). Several hands, one with a pencil, charge towards a book, which lists critical dates in Mexico’s history: 1520 (the Conquest by Spain); 1810 (Independence from Spain); 1857 (the Liberal Constitution which established individual rights); and 1910 (the start of the Revolution against the regime of Porfirio Díaz). David Alfaro Siqueiros left the final date blank in Dates in Mexican History or the Right for Culture (1952-56), inspiring viewers to create Mexico’s next great historic moment.5

Although many have said that Siqueiros' artistic ventures were frequently "interrupted" by his political ones, Siqueiros himself believed the two were intricately intertwined.

The Hero Image today (see Home Page) is one of the giant murals by David Alfaro Siqueiros that hangs at Chapultepec Castle, Mexico City.

I will return to examine the works of Diego Rivera another day.

Footnote:

- en.wikipedia.org

- theartstory.org

- theartstory.org

- en.wikipedia.org

- khanacademy.org