Magnificent Mansions – Palace of Knossos

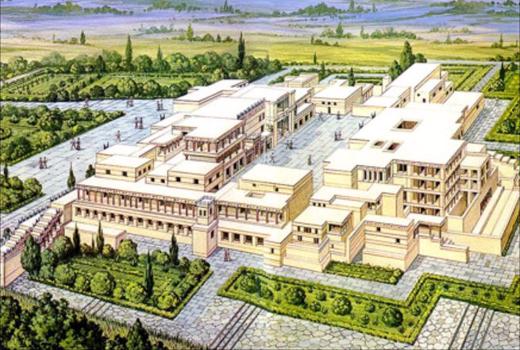

The epicentre of the refined Minoan civilisation flourished in Crete, Greece during the 2nd millennium BC and is considered one of the great civilisations of the ancient world. Of the four main palaces – Knossos, Phaistos, Mailia and Zakros, Knossos is the largest (covering 20,000 m²) Bronze Age archaeological site on Crete, but sections of it were built during different historic periods such as the Neolithic and the Classical period.

Watch an artists impression of the palace being built in this short 3D clip.

Around 1700 BC, according to one theory, a powerful earthquake shook the Aegean Sea, devastating Crete. The Palace of Knossos was destroyed, but the Minoan civilization was rebuilt almost immediately on top of the ruins and indeed the culture reached its pinnacle only after the devastation.

Scholars remain in dispute over its final demise. It appears that Knossos became an important base of operations and capital of the Mycenaeans until it was destroyed by fire and finally abandoned c. 1375 BCE. The date which traditionally marks the final end of the Minoan civilization is 1200 BCE after which there is no evidence for the culture.

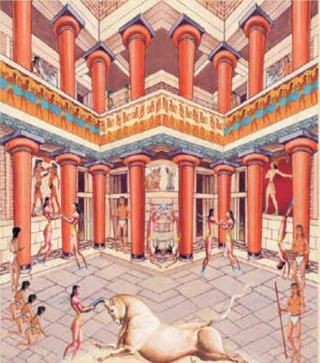

The Palace of Knossos stands as a monumental symbol of Minoan civilization, due to its construction, use of luxury materials, architectural plan, advanced building techniques and impressive size.

Steeped in mystery, Knossos has been identified with Plato’s fabled Atlantis and sung of by Homer in his Odyssey: “Among their cities is the great city of Cnosus, where Minos reigned when nine years old, he that held converse with great Zeus.” 4

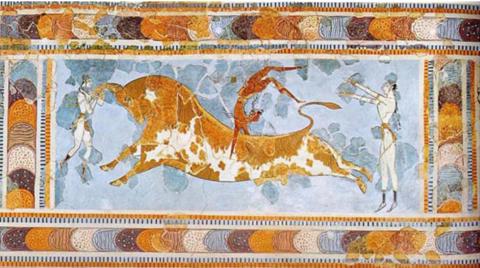

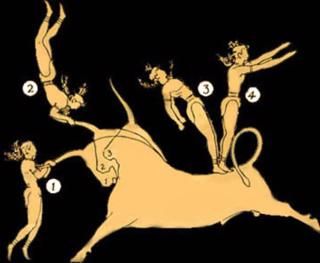

Myths also surround a unique sport or ritual, depicted in the wall painting below showing men leaping over charging bulls.

Ιn Greek mythology, the Palace of Knossos was the residence of the mythical King Minos, the son of Zeus and Europa. King Minos had the legendary artificer Daedalus construct a labyrinth in which to keep his son, the Minotaur, a mythical creature who was half bull and half man. The labyrinth was designed with such complexity that once someone entered, he could not escape. Eventually the creature was killed by Theseus.

Conjecture continues as to whether the labyrinth existed, however the image below - part of the palace and gold coin seems to indicate it did.

In 1973, even after the thrill of visiting the Acroplis in Athens and the Temple at Delphi, I was enthralled with the myths and mysteries of Knossos and the Minoan culture.

Not only a palace for the King, family, courtiers, artists and other servants, Knossos functioned as the centre of a sophisticated life. The Palace, surrounded by opulent villas was also the seat of administration and justice, an important commercial and manufacturing centre and supported workshops for all significant forms of art.

The site was discovered in 1878 by Minos Kalokairinos. The excavations in Knossos began in 1900AD by the English archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans (1851- 1941) and his team, and they continued for 35 years.

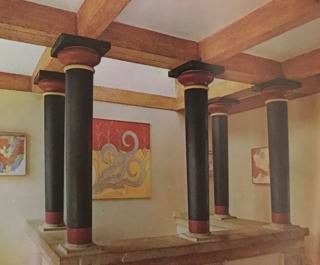

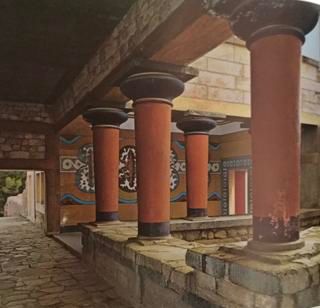

This work ensured that much of the buildings, embellishments and artefacts were preserved. When I visited Knossos in 1973 the guide mentioned that much of the restoration work was open to individual artistic licence, questioning its authenticity. An essay by Dr. Senta German on the Khan Academy website states, in part:

These are the undeniable benefits of Evans’s restorations - the smooth corniced walls, bright paintings, and whole passages stepped with balustrades at Knossos that the post cards, camera snaps, and human memory preserve, and that has translated into important support for the site—intellectually, politically, and financially.

At the same time, the Evans restorations are problematic. In some cases, what is restored does not accurately reflect what was found. Instead, a grander, and more complete experience is presented.

By definition, any sort of conservation is restoration when the modern materials are layered on the ancient and made to look harmonious in form, color and/or texture. As a result, restorations are sometimes nearly indistinguishable from authentic materials, and this is where things get tricky — such as the situation at Knossos.

These days, the critical role of restoration is conservation. The original remains must be entirely safe and not harmed in any way by restoration methods and materials. The reversibility of restorations not only has to do with the accommodation of changes in interpretation, but also with the need to leave the way open for less invasive, more gentle restoration methods in the future.

A fair argument and one we have encountered in other posts covering the meticulous restoration of paintings.

Evans had great foresight as after the Acropolis in Athens, Knossos remains the 2nd most visited ancient site in Greece.

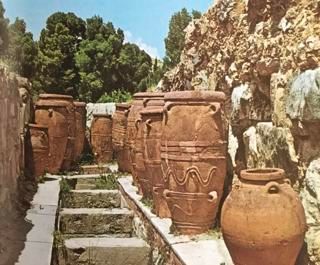

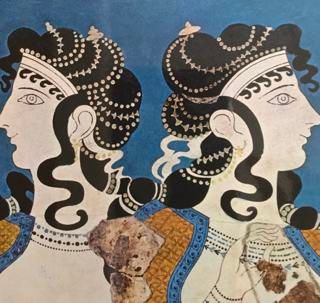

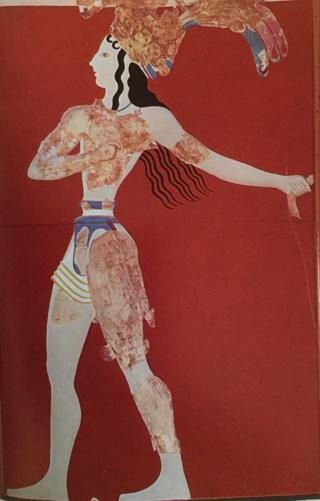

To my mind, the beautiful, restorations of architecture and wall paintings along with the preserved artefacts (some examples below, now located in the Heraklion Museum) prompted by Evans brings Knossos to life and evokes the elegance and skill of Minoan architects and painters – to this day I remember being completely captivated by Knossos.

I leave it to you to form your own opinion.

My favourites are...

Take a wander around Knossos by atching this 5min video.

Thailand and Greece were my first ever overseas destinations – both in 1973. For our next mansion, we will take a look at the Royal Palace built during the C18th in what was then called Siam.

Late Mail

And another new subscriber - we are having a "pink" week! Welcome aboard V.O'K in Australia - we are delighted that you have joined up to the AnArt4Life blog.

All images taken from Knossos and the Heraklion Museum - Brief Illustrated Archeological Guide by Costis Davaras, unless noted:

1 brown.edu

2 overflightstock.com

3 ancient.eu

4 hellenicaworld.com

5 flickr

6 Khanacademy.com