Looting of Art during WWII: Restitution

Andrew and I are back with the next post in our series on Art Crimes. Today we begin to tackle the greatest crime involving works of art the world has ever seen. We refer to, of course, the Nazi plunder (Raubkunst in German) of art works and other precious items during WWII - the stealing of art and other items which occurred as a result of the organized looting of European countries during the time of the Third Reich by agents who acted on behalf of the ruling Nazi Party of Germany.1

It is fact that more than 6 million art works - upwards 20% of the art of Europe was looted by the Nazis.2

During the Second World War, Adolf Hitler mandated that other nations’ cultural property be obtained, often forcibly, for the greater good of the state. The Nazis targeted private Jewish collections, public museums and organizations deemed to be at odds with Nazi ideology, such as Freemasons. Their goals were both financial and cultural. Hitler wanted to enrich the Third Reich and its leaders with exquisite and culturally significant treasures, sell looted art that did not reflect the Reich’s ideals for foreign currency, and create the Führermuseum, envisioned as the cultural center of the world, in his hometown of Linz, Austria. 3

This crime is way to complicated to cover in an AnArt4Life blog post and so we have decided to highlight the issue of restitution of the stolen art and the associated narrative.

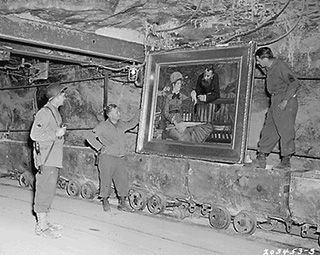

The best place to start is with The Monuments Men as many of you would have seen the film⁂ based on the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives section of the Allies, a small corps of mostly middle-aged men and a few women who interrupted careers as historians, architects, museum curators and professors to mitigate combat damage. They found and recovered countless artworks stolen by the Nazis. 5

Their work was largely forgotten to the general public until an art scholar, Lynn H. Nicholas, working in Brussels, read an obituary about a French woman who spied on the Nazis’ looting operation for years and singlehandedly saved 60,000 works of art. That spurred Nicholas to spend a decade researching her 1995 book, The Rape of Europa, which began the resurrection of their story culminating with the movie, The Monuments Men, based upon Robert Edsel’s 2009 book of the same name.5

You can read an excellent summary of the work carried out by these remarkable people in an article by Jim Morrison titled The True Story of the Monuments Men.

And for an in depth study of the contribution these people made to the restitution of the stolen art works please go to the Monuments Men Foundation which created 345 individual biographies of the Monuments Men and Women, detailing their lives, military service, and achievements. In time the Monuments, Fine Arts and Archives Section, known as The Monuments Men, would include volunteers from fourteen nations.

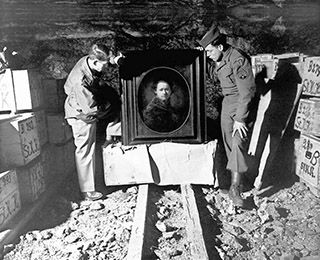

There are many, many stories surrounding the recovering of the looted art works but one that is particularly interesting concerns Rembrandt’s Self-portrait, 1645 (below) and a young GI who was asked to join the work being done by the Monuments Men in the last months of the war.

American GI Heinz Ludwig Chaim "Harry" Ettlinger (1926–2018) (shown on the right in the image on the right) working with the Monuments Men to recover art works peered through the darkness of a German salt mine and came face to face with... Rembrandt. It was a beautiful self-portrait by the Dutch artist which had once hung at a museum in his old home town of Karlsruhe in south-west Germany. Harry, whose Jewish family fled the Nazis and emigrated to the USA barely a year before the Second World War, had never seen it before because Jews were banned from the museum. He recalls: “Before we left Germany we lived just three blocks from it, but my folks said, ‘Sorry Harry, you can’t go there’. And there I was, standing right in front of it. It was incredible.” 7

Harry's unit also found a room full of explosively unstable nitroglycerin. The liquid time-bomb, which was carefully removed then safely detonated in a field, was a startling reminder of the dangers the Monuments Men faced.7

The looting of Jewish property was a key part of the Holocaust. The plundering was carried out from 1933, beginning with the seizure of the property of German Jews, until the end of World War II, particularly by military units which were known as the Kunstschutz... In addition to gold, silver and currency, cultural items of great significance were stolen, including paintings, ceramics, books and religious treasures.

Although most of these items were recovered by agents of the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program (MFAA, the Monuments Men), on behalf of the Allies immediately following the war, many of them are still missing. An international effort to identify Nazi plunder which still remains unaccounted for is underway, with the ultimate aim of returning the items to their rightful owners, their families or their respective countries. 1

Back in 2020 the Victoria and Albert Museum in London in its commitment to working to discover ownership (the provenance) of stolen art works of all types established a year long exhibition titled Concealed Histories which looked at the stories of eight Jewish collectors and their families under the Nazis.8

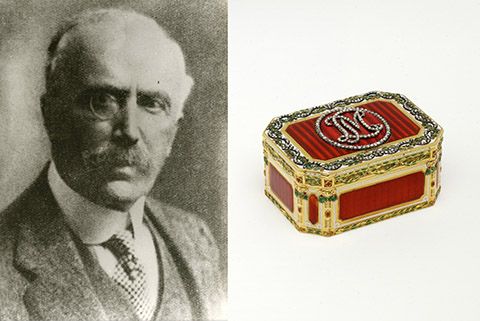

Included in the Concealed Histories exhibition were decorative arts from the The Gilbert Collection which Julie wrote on in a 2020 post for the AnArt4Life blog.

Some of the objects on display at the Concealed Histories exhibition were looted by the Nazis but were restituted after the war.

A striking example is that of a Louis XVI enamelled gold snuffbox (below) with a diamond-set monogram ‘LM’, which once belonged to Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild (1843 – 1940). A successful banker who married into the Rothschild banking dynasty, Maximilian von Goldschmidt-Rothschild was one of the wealthiest individuals in the German Empire. In November 1938, the Nazi mayor of Frankfurt exploited the anti-Semitic violence engulfing the city and forced him to sell his entire art collection to Frankfurt’s museums. After the war Maximilian’s grandson, who served in the American military, demanded the restitution of the collection. We know that this snuffbox was returned to the family in 1949 through archival records kept by the Museum of Applied Arts and the City of Frankfurt. 8

However, for many of the objects in the Gilbert Collection, the provenance is not known. A striking example (as shown below) is that of a colourful Johann Christian Neuber snuffbox, decorated with numerous hardstones, which once belonged to Eugen Gutmann (1840 – 1925), the founder of the Dresdner Bank. 8

In 1996, the V&A received the only known complete copy of the inventory of the so-called ‘degenerate art’ confiscated by the Nazis from German public collections.

You can view the inventory by clicking here.

The V&A has been a driving force behind the efforts of UK museums to systematically research their collections in order to identify pieces which had been looted by the Nazis and were not restituted after the war.

Also of interest is a current exhibition Afterlives: Recovering the Lost Stories of Looted Art being held at the Jewish Museum in New York City until 9 January 2022 where the difficult process of protecting art throughout and after the second world war is examined and celebrated.9

During World War II, untold numbers of artworks and pieces of cultural property were stolen by Nazi forces. After the war, an estimated one million artworks and 2.5 million books were recovered. Many more were destroyed. This exhibition chronicles the layered stories of the objects that survived, exploring the circumstances of their theft, their post-war rescue, and their afterlives in museums and private collections.

To read more about the exhibition please follow this link to an excellent article by Jordan Hoffman of The Guardian title Afterlives: the incredible stories behind recovered Nazi-looted art.

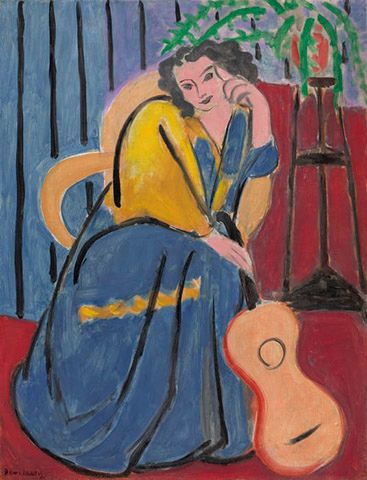

One example from the exhibition is given below. Henri Matisse's Girl in Yellow and Blue with Guitar was painted in 1939 a year before the Nazi's occupied Paris and was banned from being shown in German museums. Paul Rosenberg, a French-Jewish collector owned the painting and managed to keep it hidden from the Nazi until he fled the country. The painting ended up in the jeu de Paume gallery in Paris which the Nazis had turned into their largest warehouse for looted art. Rosenberg did get his painting back after the war. 11

We must remember that the plunder and looting of art and other treasures was not limited to the Third Reich, however. The Soviet and American armies also participated, the former more thoroughly and systematically, the latter at the level of individuals stealing for personal gain. Other Axis countries also looted private Jewish collections.10

Thousands and thousands of stolen art works from the WWII remain undiscovered. It is believed that many pieces are hanging (unidentified as stolen) in European museums and galleries and the governments of many countries have been criticised for not making a better effort to identify and return the stolen works to their original owners.

Tomorrow we will look at a painting that was stolen by the Nazis and found in a salt mine but has in fact been stolen 13 times and is believed to be the most stolen painting in the world.

⁂ The Monuments Men is a 2014 war film directed by George Clooney, and written and produced by Clooney and Grant Heslov. The film stars an ensemble cast including Clooney, Matt Damon, Bill Murray, John Goodman, Jean Dujardin, Bob Balaban, Hugh Bonneville, and Cate Blanchett.

The film is loosely based on the 2007 non-fiction book The Monuments Men: Allied Heroes, Nazi Thieves and the Greatest Treasure Hunt in History by Robert M. Edsel and Bret Witter. It follows an Allied group from the Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives program that is given the task of finding and saving pieces of art and other culturally important items before Nazis destroy or steal them, during World War II. 1

Below is the Official Trailer for the movie which you might find interesting and spur you on to watch the movie if you missed it when it did the rounds of the theatres.

Credits

1. en.wikipedia.org

2. archives.gov

3. ushmm.org

4. theconversation.com

5. smithsonianmag.com

6. businessinsider.com.au

7. mirror.co.uk

8. vam.ac.uk

9. thejewishmuseum.org

10.ushmm.org

11.pressreader.com